ROBERT HEINECKEN

Waking Up in News America

source: cherryandmartin

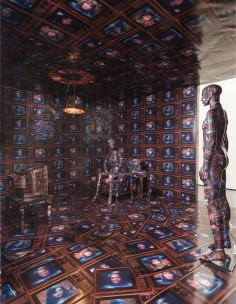

Heinecken’s “Waking Up in News America” is a significant work that has not been seen in almost two decades. The room-sized installation investigates two of Heinecken’s deep concerns: mass media and the affects of one particular form of mass media–the television. “Waking Up in News America” is a room in which every surface–the walls and floors, the figure sitting in a chair and the range of household objects that make up this odd ‘domestic’ environment–are completely covered in images shot from the TV. The effect is to suggest that we are formed–in every way–by the omnipresent medium.

Trained as a graphic designer and printmaker, Heinecken was long interested in how our sense of self is shaped by news, pornography and advertising, and considered both broadcast and print media throughout his career. For Heinecken, as the saying goes, “we are what we eat.” In works going back to the mid-60s, Heinecken’s combinations and manipulations of found images and text serve as an important link between historical Surrealism and later Appropriation. But it was in the late 1970s, after a series of major events in his life–including a fire that destroyed his studio in 1976–that Heinecken charts an important new course, injecting his own subjectivity as a thing to be dealt with, purposefully blurring the lines between who he was and who he was assumed to be by the mass media messages that surround us all and make up so much of American visual life.

In the late 70s, Heinecken began experimenting with texts that he either wrote himself or adapted using the language, format and mode of address found in magazine articles and talk television. Initially the images, taken with a Polaroid SX-70, were pictures of Heinecken, his friends and his immediate environment. Later pieces paired texts with images from magazine pages and collaged images from magazine pages. For a series of works entitled “Socio/Fashio Lingerie” (1981), Heinecken presents pairings of magazine collages with lingerie advertising blurbs, often accompanied by a handwritten-text that regurgitates much of the lascivious text of the lingerie blurb. At first, this seemingly handwritten and lascivious text is assumed to be Heinecken’s own thoughts. It is only on closer inspection that it reveals to be almost entirely derived from the advertising copy.

As critic Matt Biro writes, “This sort of scripting of experience was being carried out on a much larger scale in the world of television, where the consumer fantasies of corporate broadcasting were irrevocably inserted into the intimate domestic settings of the home.” (Matt Biro, “Reality Effects,” Artforum, October 2011, p. 255). The text of “Waking Up in News America” presents the viewer as if at the dawn of a new era formed by image and technology: “Waking up in News America with mostly blue eyed blondes. Pretending another Occidental sunrise. Sensing the technologic banzai.” “Waking Up in News America” (1986) is a quintessential 80s piece, a statement on the intrusiveness of television, its fantasies and consumerism, all driven by the psychological power of the medium’s ability to blend language and image.

Also included in Cherry and Martin’s exhibition will be a number of Heinecken’s videograms. To make these concrete photographic works, Heinecken held unexposed photo paper up to the television set, turning it on and off to expose the image. For Heinecken, the motif of the TV network newswoman is a favorite narrative foil who seemingly legitimates the madness of the media world. Cherry and Martin’s exhibition will also include a selection of Heinecken’s magazine print-throughs from the late 80s and early 90s, in which two sides of a magazine page are reproduced as one image, bringing out unexpected associations and meanings.

In 2014, a retrospective of Robert Heinecken’s work, organized by Eva Respini with Drew Sawyer, opens at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (March 15 – June 22, 2014). The show travels to the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (October 5, 2014 – January 7, 2015). A second solo exhibition of Heinecken’s work, curated by Devrim Bayer, opens at Wiels in Brussels in May (May 29 – August 17, 2014). Current and recent solo and group museum exhibitions include “Robert Heinecken: Le Paraphotographe,” Musee d’Art Moderne et Contemporain (Geneva, Switzerland); “The Photographic Object 1970,” Le Consortium (Dijon, France); “The Shaping of New Visions: Photography, Film, Photobook,” Museum of Modern Art (New York, NY); “The Polaroid Years: Instant Photography and Experimentation,” The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College (Poughkeepsie, NY); “Sinister Pop,” Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, NY); and “Color Rush: 75 Years of Color Photography in America,” Milwaukee Art Museum (Milwaukee, WI). Cherry and Martin’s exhibition will run concurrent with an exhibition of the artist’s work at Marc Selwyn Fine Art in Los Angeles focusing on an investigation of Heinecken’s “Case Study in Finding an Appropriate TV Newswoman” (1984).

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: dailyserving

Robert Heinecken is an artist who is hard to pin down. A photographer who rarely used a camera, he founded UCLA’s photography department in 1964. Skeptical of the documentarian role of photography, he mined images from mass media, prefiguring the appropriation strategies of Pictures Generation artists like Richard Prince and Sherrie Levine by at least a decade. Despite this, he was never able to achieve the notoriety accorded these artists.

Accompanying these modest two-dimensional works is a large-scale installation titled Waking Up in News America (1986). Seen here for the first time in almost two decades, the piece consists of a room plastered wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling with photolithographs of televisions featuring images of female newscasters. They also cover everything in the room, including two mannequins, a lamp, a television, a chair, a book, etc. Although impressive in its execution, I found myself underwhelmed in the midst of this TV environment. The pervasive influence of mass media may be so ubiquitous at this point that its visual manifestation no longer has the same impact that it did thirty years ago. The photolithographs also lack the presence of the videograms, appearing dull and flat when compared with the supernatural glow of these earlier works.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: moma

Robert Heinecken (1931–2006) was a pioneer in the postwar Los Angeles art scene. Describing himself as a “para-photographer,” because his work stood “beside” or “beyond” traditional ideas associated with photography, Heinecken worked across multiple mediums, including photography, sculpture, video, printmaking, and collage. Culling images from newspapers, magazines, pornography, and television, he recontextualized them through collage and assemblage, double-sided photograms, darkroom experimentation, and rephotography. Although Heinecken was rarely behind the lens of a camera, his photo-based works question the nature of photography and radically redefine the perception of it as an artistic medium. His works explore themes of commercialism, Americana, kitsch, sex, the body, and gender. In doing so, they also expose his obsession with popular culture and its effects on society, and with the relationship between the original and the copy.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: zonezero

Robert Heinecken, artista que cambió la manera de ver la fotografía dentro de la cultura norteamericana murió el pasado 19 de mayo en Albuquerque en Nuevo México a los 74 años de edad.

Heinecken se había mudado a Nuevo México de Los Ángeles, en donde había vivido y trabajado durante 50 años. Había padecido del síndrome de Alzheimer desde 1994 dijo su esposa Joyce Niemanas.

En la década del 60, Heinecken abordó la fotografía de una manera diferente a lo que se había hecho en el medio. Él se llamaba a sí mismo un “para-fotógrafo” por que su trabajo estaba “junto” o “más allá” de las ideas tradicionales de la fotografía.

Esencialmente, el artista decidió que en los albores de la explosión mediática que caracteriza la vida contemporánea, ya había suficientes fotografías en el mundo. En lugar de hacer más, manipuló las ya existentes. Su arte tenía la intención de aclarar, revelar y a veces confundir los códigos sociales, políticos y artísticos subliminales contenidos en ellas.