MARK HANSEN & BEN RUBIN

Mark Hansen and Ben Rubin, “Moveable Type” (2007).

source:artnerdcom

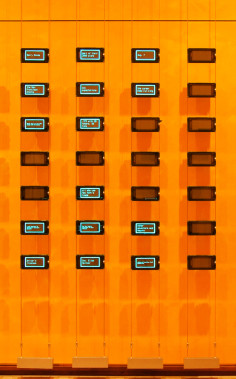

Many lobbies of corporations in New York feature art collections that are accessible to the public. The New York Times building commissioned a site specific piece for their Times Square lobby. Created by tech wizards Ben Rubin and Mark Hansen, the piece, “Moveable Type,” culls headlines and quotes from the newspaper’s 150+ year old archive. Set to the somehow calming chatter of vintage typewriters, the quotes are emblazoned across 560 screens, which stretch across the walls on either side of the lobby. The algorithm is specific- quotes starting with “I” or “you” are paired together, news is categorized into numbers, letters to the editor appear slowly and purposeful, as if the author were typing them in real time. The screens sometimes move in waves, and the viewer can feel a hundred years of news swim over and past them. The movement and frequency of the data that sweeps across each screen is directly affected by current news as well; it also draws content from a live feed from The New York Times in real-time, and also from comments from readers of The Times’ website. The screens also display basic patterns and images, such as the outline of states and countries. Ruben and Hansen compare Moveable Type to a living organism, and they couldn’t be more correct. If The New York Times were a being, this would be it, living and breathing news, the 560 screens acting as lungs and lifeblood.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source:nytimescom

The words flash out and then fade, like something from the cut-up prose of William S. Burroughs or the disjointed Americana of John Ashbery: “You just have to react.” “You won’t be asked to leave, but you will want to leave.” “I steal it from her every chance I get.” Sometimes they unite vaguely and ominously: “Five-year-old girl’s finger.” “One shot.” “Two of his lawyers.” “Fifteen years in prison.” At other times they seem sentient, asking the right questions (and maybe watching television): “Tony Soprano?” “And where’s all the blood?” As poetic as they might sound, these phrases did not bubble up from the subconscious of a writer or latter-day Dada collagist. They were culled from another kind of memory, a vast collective one that is stocked and ordered every day (and these days, every minute) by reporters, editors, photographers, bloggers, Op-Ed contributors, letter writers and inveterate e-mailers: the databases of The New York Times. They comprise tens of millions of words that have appeared in the newspaper since its founding in 1851 and that appear continuously in its online version. Since The Times moved in June from its longtime home on West 43rd Street in Manhattan to its new, almost completed tower designed by Renzo Piano on Eighth Avenue between 40th and 41st Streets, two men — an artist, Ben Rubin, and a statistician, Mark Hansen — have all but taken up residence in the building’s cavernous lobby, huddled most days around laptops and coffee cups on a folding table. Flanking them on two high walls are 560 small screens, 280 a wall, suspended in a grid pattern that looks at first glance like some kind of minimalist sculpture. But then the screens, simple vacuum fluorescent displays of the kind used in alarm clocks and cash registers, come to life, spewing out along the walls streams of orphaned sentences and phrases that have appeared in The Times or, in many cases, that are appearing on the paper’s Web site at that instant. They are fished from The Times databases by computerized algorithms that Mr. Rubin and Mr. Hansen have designed that parse the paper in strange ways, selecting, for example, only sentences from quotations that start with “you” or “I.” Or sentences ending in question marks. Or just the first, tightly choreographed sentences of obituaries. The content of the permanent installation, called “Moveable Type,” is drawn not only from the words that The Times reports but also, in real time, from the search terms and Web commentary pouring in from thousands of readers around the world, capturing what Mr. Rubin called “both the push and the pull” of the newspaper. “We want it to feel almost like an organism that is living and breathing and consuming the news,” Mr. Rubin said, adding that someone who had not seen the paper or Web site would be able to watch the screens for several minutes and begin to get a sense of that day’s biggest events, though in a way that might feel more like floating on the newspaper’s stream of consciousness than reading it. And if you happen to come into the lobby late at night, he and Mr. Hansen added, the artwork, like the paper, will be mostly asleep but “dreaming” — rummaging, “Finnegans Wake”-style, through articles and captions and headlines going back generations. David A. Thurm, the chief information officer at The New York Times Company, said he had read about Mr. Rubin and Mr. Hansen in a magazine, then went to see a creation of theirs called “Listening Post,” which eavesdropped on the cacophony of the world’s Internet chat rooms and became a minor sensation during a 2003 stay at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Mr. Thurm said that he and others involved in the newspaper’s new headquarters felt that a similar concept could create a kind of “dynamic portrait” of The Times that functioned, in a way, like a homage to the news ticker but one that followed the advice of Emily Dickinson: “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant.” The installation, which was commissioned by The Times Company and its development partner in the building, the Forest City Ratner Companies, is still being fine-tuned but is now operating during the day. On a recent viewing it seemed to rouse itself to life, its screens reeling out words and, from hundreds of small hidden speakers, issuing the din of typewriters, the lost music of newsrooms. As clackety and coldly mechanical as “Moveable Type” is, the artists said, people who wander by tend to draw close to it, as if to hear the pronouncements of an oracle or to warm their hands with the heat of information. “People seem to want to touch it,” Mr. Hansen said. Mr. Rubin, smiling paternally, said, “We really don’t want people to touch it.”

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source:stickelcombr

Visitei pela segunda vez o novo prédio do New York Times, na 40 St. x 8 Av., desta vez com as obras completas.? O projeto de arquitetura de Renzo Piano é fantástico, abandona os mármores, é todo em metal, usa cores fortes, muito cinza e pisos de madeira. O mais interessante é uma instalação no hall de entrada, feita por Mark Hansen e Ben Rubin “Moveable Type” com centenas de pequenos monitores onde permanentemente aparecem fragmentos dos arquivos eletrônicos do jornal, palavras, frases, cotações, lugares, palavras-cruzadas, etc… em uma infindável série de combinações.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source:klcbsnet

The New York Times Tower di sisi timur Eight Avenue, pencakar langit 52 lantai setinggi 319 meter, untuk perkantoran, dengan penghuni utama, kantor harian the New York Times. Lobby umum di lantai dasar gedung memiliki sebuah instalasi seni yang disebut Moveable Type, karya bersama seniman New York Ben Rubin dan Mark Hansen, Professor Statistics di the University of California. Karya seni itu terdiri dari 560 display digital disusun masing-masing dalam dua grid yang terdiri dari 7 baris dan 40 kolom. Masing-masing grid memiliki panjang 16 meter dan tinggi 1½ meter. Moveable Type menggunakan algoritma yang dikembangkan oleh para seniman untuk mengurai output harian dari Koran New York Times, serta arsip 150 tahunnya untuk membentuk sebuah display, di lobby umum The New York Times Tower.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source:artfuturaorg

En 1928, el New York Times instaló sobre la fachada de su sede en el corazón de Manhattan el ticker, un dispositivo mecánico que permitía mostrar a los peatones los titulares de las noticias que iban llegando a su redacción. Por primera vez, los flujos de información se convertían en arquitectura, en parte del paisaje urbano. Se trataba del primer paso hacía la avalancha de textos e imágenes en movimiento que caen hoy sobre los turistas en Times Square. Desde hace unas semanas, el ticker ha vuelto al mítico diario neoyorquino, reencarnado en una ambiciosa instalación que ocupa la entrada de su flamante nuevo edificio en la octava avenida. Moveable Type, de Ben Rubin y Mark Hansen, es un retrato en tiempo real de una de las fábricas de información más influyentes del mundo, y de las pequeñas historias que se ocultan en su interior. Quinientas sesenta pequeñas pantallas, repartidas a ambos lados de un pasillo, reproducen una cascada interminable de frases que a los segundos se desvanecen. Proceden de los artículos que aparecen en el periódico de ese día, pero también de las búsquedas que realizan los usuarios de la web, y de los comentarios que dejan en sus historias. Para el visitante que se para frente a las pantallas es cómo leer un diario escrito en forma de monólogo interior joyceano, en que la actualidad del día empieza a revelarse lentamente a través de destellos y fogonazos de texto. Hansen y Rubin han programado distintos algoritmos que recorren la base de datos del sistema informático del periódico para crear diferentes “escenas”, paisajes de fragmentos de texto con estructuras similares. Algunas muestran todas las frases que arrancan con una cifra (”un disparo”, “dos de sus abogados”), o las que empiezan con “yo” o “tú”. En otras secuencias, podemos leer la primera frase del obituario o de la crónica de la boda de personajes que nunca llegamos a conocer. Renzo Piano, el célebre arquitecto responsable del rascacielos, sugirió a los artistas que concibiesen el proyecto como si fuese una especie de organismo vivo que habitase en el edificio. El sistema reproduce el ritmo cíclico de una redacción, perezosa por las mañanas y cada vez más frenética a medida que va acercándose la hora del cierre. Por las noches, Moveable Type “sueña”; el ordenador búcea en el subconsciente del periódico, extrayendo textos de sus ciento cincuenta años de archivo relacionados de alguna manera con las noticias que han acaparado los titulares ese día. La memoria del New York Times del siglo XX está presente también en los diferentes sonidos que emiten las pantallas. La percusión del teclear de las máquinas de escibir, el zumbido de los teletipos…la música perdida de las viejas redacciones de periódico, desaparecida cuando la maquinaria pesada con que se elaboraba las noticias fue sustituida por redes de ordenadores. Para capturar pequeños fragmentos de historias personales en la marea de datos que genera diariamente el que es quizás el periódico más importante del mundo, los creadores de la instalación hacen uso del “data mining” (minado de datos), una técnica de análisis estadístico que permite descubrir y relacionar elementos comunes en una gran masa de información. En proyectos como We Feel Fine, de Jonathan Harris, el análisis informático de masas de datos como las entradas que se escriben diariamente en millones de blogs es la puerta de acceso a las confesiones íntimas expresadas anónimamente desde alguna parte de la Web. Otras obras cómo Ambiente de Estereo Realidad 4, de José Carlos Martinat y Enrique Mayorga (actualmente en exhibición en la exposición “Emergentes”, del centro Laboral de Gijón) buscan a través de Google entre la la inmensidad inabarcable de la Red ideas y expresiones concretas basadas en el verbo “deber”. Para el crítico de los nuevos medios Lev Manovich, la forma cultural predominante del siglo XXI (la heredera de la novela y el cine como vehículo que servirá para retratar una época) será la base de datos. Generar y clasificar estas grandes masas de datos se ha convertido en una de las actividades principales de la ciencia, la economía y, desde el despegue de la Web, la sociedad civil.La instalación de Rubin y Hansen es una fascinante apuesta por un nuevo lenguaje que sirva para recorrerlas e interpretarlas. Moveable Type es el producto más reciente de la fértil colaboración entre el artista neoyorquino Ben Rubin y el científico Mark Hansen, profesor de estadística en la universidad de UCLA y experto en redes de sensores medioambientales. La colaboración entre ambos comenzó con Listening Post (2002), un hito de los proyectos artísticos basados en la representación dinámica de la información. En ella, un ordenador rastrea constantemente cientos de chats, foros y grupos de noticias en la Red para cazar retazos de comentarios y pensamientos, y verterlos sobre ristras de pequeñas pantallas de texto. El próximo año podrá verse en el Reina Sofía de Madrid.