SHIGERU BAN

日本建築師阪茂

坂茂

شيجيرو بان

שיגרו באן

시게루 반

Шигеру Бан

source: japantimescojp

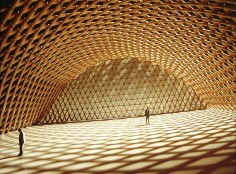

Houses of card: Model of the Japan Pavilion at Expo 2000 in Hannover

Every profession has a fundamental underlying mission that is rooted in some basic human need. For medicine, it is health; for the law; it is justice. In the case of accountancy, it is the universal human need to minimize tax.

Architecture is rooted in the basic human need for shelter. But the profession today pays little attention to situations where the need for shelter is most urgent, such as after a disaster. Much of architecture’s energy, and the creativity of its most celebrated practitioners, is preoccupied with constructing glamorous baubles for the gratification of wealthy individuals and corporations. It is rare to find an architect as committed to the provision of shelter as to that of architectural delight.

Shigeru Ban is such an architect. Born in 1957, Ban first made his name in the mid-1990s with his use of lightweight paper tubes as structural and enclosing elements in buildings. In paper tubes, Ban found a material that is cheap, strong, sustainable, and readily available, but its wholesome brown blandness is hardly glamorous. Yet Ban’s portfolio also boasts eye-watering houses overlooking sea horizons with walls that roll completely away; a luxury high-street shop with futuristic cylindrical glass elevators; and a spectacular museum with a roof structure that appears to have been woven in timber. Most surprising is his parallel career as an architect of emergency shelters for people in the most abject situations — victims of war, earthquakes, and tsunamis.

These varied facets of Ban’s career are currently being shown in a large solo exhibition at Art Tower Mito, in Mito, Ibaraki Prefecture. Titled “Architecture and Humanitarian Activities,” the show spans the full breadth of his career, from an early design for an exhibition on the Finnish master Alvar Aalto, to his recent audacious structures in France and Korea executed in massive interlacing strands of timber — an innovative constructional approach that opens up exciting new spatial possibilities. As the title suggests, Ban’s projects for disaster relief form an intrinsic part of the story.

Architecture exhibitions face the inevitable challenge of not being able to show their most representative artifacts — buildings. Models and photographs are the usual expedients, but these are inevitably poor substitutes for the material and spatial force of real constructions. A strength of this show is the use of large-scale models or full-scale mockups of built elements, of a size and presence that invites direct engagement with one’s body, enabling their architectural qualities to be tangibly experienced.

This treatment has been particularly reserved for the disaster-relief projects. You can squat in the basic tents built of paper tubes and tarpaulins used by Rwandan refugees, the project that kicked off Ban’s career as an “humanitarian architect.” You can step inside the dignified “Paper Log House,” used as temporary housing after the 1995 Kobe quake, and later in Turkey and India. You can wander among the simple privacy partitions built of paper tubes and canvas curtains that Ban and his apprentices erected in dozens of emergency shelters across Tohoku after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. Most ambitiously, you can even get a sense of the living conditions in a temporary housing facility built from converted shipping containers that Ban has recently erected in Onagawa, Miyagi Prefecture, as a full-size unit has been built in the courtyard of the museum, complete with furnishings supplied by Muji.

All this admirable verisimilitude, however, reveals a fundamental aesthetic difficulty for the curator, Sayako Kadowaki, one which illuminates the nature of Ban’s architecture. For want of better words, this problem might be termed the “banality of the real.” The nagging question faced by a casual visitor wandering through the mockups is: “How should I be looking at these things? As works of art? Or as products in a trade show?” The closer the displayed artifacts get to “the real thing,” the less aura they bear as aesthetic objects, and the less effectively they work as receptacles of conceptual or emotional content. Eventually these dimensions evaporate, replaced by a set of technical or practical concerns, of interest to be sure to practitioners, but which no longer direcltly engages aesthetic experience or cultural questions.

This exhibition reveals how conscientiously Ban takes architecture’s fundamental mission. The aesthetic delight or experiential rush that may come from the resulting buildings arises as an outcome of the core concern: providing shelter or space, economically, efficiently, rationally. In this, Ban’s architecture is rooted in the modernist credo that function begets beauty. Such an architecture sees its main task as “problem-solving.” Disasters create huge problems; architecture’s mission is to solve them.

Another approach to architecture sees its mission less as solving problems, but as posing questions. A disaster then becomes a giant existential question mark, asking, as fellow architect Toyo Ito has recently done: “What are we here for? What is architecture for? Is architecture even possible here?” These are questions that Ban’s architecture does not consider, for as this exhibition suggests, it already has the answers.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: architourinfo

日本建築師阪茂(Shigeru Ban),是現今國際最受矚目的建築師之一,他的創作遍佈世界,從東京三宅一生的住家 、 2000 年德國漢諾威萬國博覽會日本館、紐約「遊牧博物館」到法國龐畢度中心新館的設計等,都可見其作品。

阪茂(Shigeru Ban)最廣為人知的特色,是對自然建材的運用,尤其大膽採用紙管材料,創發一系列「紙建築」,充分展現與自然環境融合的智慧。他不僅是國際知名的建築師,亦是一位人道主義者,他曾說過:「二十世紀的建築大師為大眾建造公共建築,而冷戰後一代的建築師應該為少數人服務,例如種族衝突的受害者和無家可歸的人。」 他運用紙建材輕巧、組裝迅速的特質,為阪神大地震的災民設計紙教堂及臨時房屋,也為非洲盧安達難民搭蓋避難所及住家;「紙建築」在他的理念中一種 結合高科技的創作,更深含對人類社會的關懷與責任。

阪茂開始嘗試在幾個建造項目中使用紙筒。為了取得建設部對紙結構的許可阪茂設計了「紙之家」(Paper House)。1993年,阪茂(Shigeru Ban)終於獲得許可得以建造「紙之藝廊」和「紙之家」。 在一系列的成功探索之後,自1994年起,阪茂開始利用自己所取得的獨特經驗,積極地介入了世界各地的公益性建造工程,如幫助日本阪神地震、盧旺達內戰、土耳其地震後的難民興建臨時性的庇護所。

2000年,阪茂實現了他的最大規模的紙材料構築 – 漢諾威博覽會日本館。同年他在紐約的現代藝術博物館雕塑庭院中豎立起「紙之拱」。 阪茂相信紙筒作為建築材料有著寬廣的前景。它們對環境的威脅甚小。儘管比其它材料脆弱,但只要使用得當,同樣有潛力可作多種用途。在他看來,紙會被愈加廣泛地得以運用,而與之相應的持續發展的技術顯得越來越有必要。

阪茂的建築設計並不只限於紙材料,他一直在超越人們對他的期待。儘管初看上去是在鼓勵設計師們重新思考建築材料的問題,他真正想要的卻是對建築學可及範圍的一個全新的定義。 在由普林斯頓建築出版社出版,他的作品集的前言中,阪茂這樣形容他對紙建築設計的探索:「我曾一直有這樣的印象,有些東西不管結構設計看上去怎麼富有邏輯,就是不可能建出來。很快這種想法就消失了,任何事都是可能的」。