GRETE STERN

source: jwaorg

In 1935, two months after arriving in Argentina, Grete Stern and her husband Horacio Coppola presented what the magazine Sur called “the first serious exhibition of photographic art in Buenos Aires,” which comprised work produced in Germany and London between 1929 and 1935: portraits, compositions, advertising photographs and landscapes. Her work showed an unconventional approach to photography: advertisement collages and studies with crystals, objects and still-lifes. Even the most accepted subjects at the time, such as portraits and landscapes, were done in unconventional ways: perfect definition, wide chromatic spectrum, flat lighting, simple poses and untouched negatives. Between 1935 and 1981 she continued with this work in Argentina, adding an important series of photomontages, reproductions of art work and portraits. Stern brought with her from Germany a modernist sensibility, developed in bohemian Berlin and at the legendary Bauhaus School, that shook up the staid approach to photography in Argentina at that time and established her as one of the founders of Argentine modern photography.

Grete Stern was born in Elberfeld, near Wuppertal, Germany, on May 9, 1904. She was the first child of Frida Hochberger and Louis Stern, who died in 1910. Her family was involved in the textile business and often traveled to visit relatives in England, where Stern attended her first years of elementary school. She studied piano and guitar and from 1923 to 1925 studied graphic design with Prof. Ernst Schneidler at the Kunstgewerbeschule (Am Weissenhof) in Stuttgart. In 1926 she worked as a freelance graphic design and advertising artist in her home town of Wuppertal. After seeing a photography exhibition of Edward Weston and Paul Outerbridge she was inspired to study photography.

In 1927 Stern moved to Berlin to live with her brother Walter, who was working as a film editor. He sent her to meet photographer Umbo (Otto Umbehr) who in turn sent her to take private lessons with Walter Peterhans, a photographer well known for his meticulously produced still lives. In 1928 Peterhans also accepted Ellen (Rosenberg) Auerbach as a student. Stern and Auerbach began a profound friendship that lasted throughout their lifetime. “He taught us to see photographically. For him the camera was not just a mechanism to take a photograph. It was a new way of seeing,” she said in an interview in 1992. In 1930 Walter Peterhans was named Master of Photography at the renowned Bauhaus School for art and design in Dessau. Using the proceeds from an inheritance Stern bought his equipment and with Auerbach started a photography studio for advertising, fashion and portrait photography. They thought that calling it “Rosenberg [Ellen’s birth name] and Stern” sounded too much “like a Jewish clothes manufacturer” so they called it ringl+pit, after their childhood nicknames (Ringl for Grete, Pit for Ellen). They decided to sign all their work together.

In the early 1930s modern advertising was at its beginning and left ample room for creative exploration. ringl+pit’s advertising work represented a departure from current styles, by combining objects, mannequins and cut-up figures in a whimsical fashion. Stern and Auerbach were also influenced by the intense creative environment prevalent in Berlin at the time. Their work explored a new way of portraying women, in line with the image of the New Woman that was emerging at the time. There was a subtle irony in their work about what was accepted and expected of women that was a marked departure from the dominant image of women. Grete’s background in graphic design also came in handy. “What I liked very much was the combination of photography with a well done typography, with well done letters. That was my specialty,” said Stern.

In 1933 ringl+pit’s work received positive reviews in the magazine Gebrauchsgraphik and in 1933 they won first prize for one of their advertising posters at the Deuxième Exposition Internationale de la Photographie et du Cinema in Brussels.

In April 1930 Grete Stern followed Peterhans to Dessau to continue her studies. There she met an Argentine photographer and fellow Peterhans student, Horacio Coppola. Auerbach kept the studio running and Stern returned to continue their work together in March 1931. She went back to the Bauhaus for further studies with Peterhans between April 1932 and March 1933.

In 1933 the Bauhaus closed its doors, hounded by the Nazis. Although not an activist, Grete was sympathetic to leftist movements and her friends there warned her of the upcoming dangers posed by the new regime. With antisemitism becoming more and more aggressive, in early 1934 Stern left the ringl+pit studio and with her brother Walter emigrated to London. She was able to take with her all of her photographic equipment and furniture. These were productive years for Stern: she opened a photographic and advertisement studio and continued her work on portraits, photographing her friends from the community of German exiles, including Bertolt Brecht, Helene Weigel, Karl Korsch and Paula Heimann. The French magazine Cahiers d’Art includes an article on the ringl+pit studio. Ellen Auerbach had also had to leave Germany and after a brief stay in Palestine joined Stern in London. Their last work together was photographs for a maternity hospital brochure.

Grete’s brother Walter emigrated to California in 1934. Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola were married in 1935 and traveled to Argentina, Coppola’s native country. In October 1935, shortly after arriving in Buenos Aires, Stern and Coppola mounted a joint exhibition that is considered the first exhibition of modern photography in Argentina. Unsure whether she wanted to stay with Coppola, a pregnant Stern went back to London, where her daughter Silvia was born on March 7, 1936. A few months later she decided to return to Coppola and Argentina, where she lived the rest of her life.

Between 1937 and 1941 Stern and Coppola operated a photography, graphic design and advertising studio in Buenos Aires. They tried to create a modern studio but they were too far ahead for the local way of working. At that time there were no advertising agencies in Buenos Aires. In 1943 Stern presented her first one-woman exhibition in Buenos Aires, which was comprised entirely of portraits. Her stark style was a marked departure from the dramatic and overlit pictures that were prevalent in Argentina at the time. Working as a woman in a male-dominated society was also a challenge.

Stern and Coppola’s home was always open to receive Jewish and political exiles from Europe. They forged a community of support, work and cultural activities with the intellectuals and artists escaping persecution, who also became models for her portrait work.

In 1940 the couple moved to a Modernist house built in the outskirts of the city, designed by architect Wladimiro Acosta. It had a studio with natural light and darkroom facilities. A son, Andrés, was born the same year. The following year Stern and Coppola separated. The house became a meeting place for young artists and writers, many of them Coppola’s friends, both Argentine and exiled foreigners. They met to show their work and discuss cultural matters. For example, in 1945 the Madi arts group (Movimiento de Arte Concreto Invención) exhibited for the first time at her house.

Stern used the gatherings in her home as an opportunity to photograph her visitors. Among her subjects were exponents of the avant-garde in the arts and letters, including Jorge Luis Borges, Clément Moreau, Renate Schottelius and others. Stern’s photographs are a precious archive of intellectuals and artists of the time. “I made people see what I saw in a face. I never liked those hard shadows which were very often used at that time. Some critics thought that it was a bad way [to photograph], they said it’s all gray, it doesn’t say anything. But in the end they did like it.” said Stern. These photographs are studies of faces and heads, with simple backgrounds that do not distract from the main subject.

By the mid-1940s Stern was a well-established photographer and graphic designer in Buenos Aires. Throughout her career her photographic subjects were quite varied and included portraits, advertising, nature, cityscapes and indigenous people in the North of Argentina. Stern’s portrait work was often done for pleasure, but her subjects became clients when they saw the product of her work. She also worked with architectural studios and in 1947 the magazine Nuestra Arquitectura published an article on architect Amancio Williams, with Stern’s photographs. At this time she started singing in choirs, which she would continue to do for the next forty years.

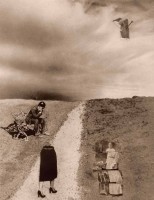

In 1948 Stern was offered the unusual assignment of providing photos for a column on the interpretation of dreams in the popular weekly women’s magazine Idilio. The column, entitled “Psychoanalysis Will Help You,” was a response to dreams sent in by readers, mostly working-class women. It was written under the pseudonym Richard Rest by renowned sociologist Gino Germani, who later became a professor at Harvard University. The result was a series of about one hundred and fifty photomontages produced between 1948 and 1951 that show Stern’s avant-garde spirit. In these photomontages she portrays women’s oppression and submission in Argentine society with sarcastic and surreal images. The photomontage was an ideal way for Stern to express her ideas about the dominant values.

In 1956 Stern created and directed a photography workshop at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Fine Arts Museum,) where she worked until her retirement in 1970. There she met numerous artists and documented their portraits.

An invitation in 1959 to teach a photography seminar at the University of the Northeast, in Resistencia, Chaco, gave a creative impulse to her work. In 1964 she obtained a grant from the Fondo Nacional de las Artes and traveled through the northeast of Argentina, producing more than eight hundred photos portraying the lives, craftwork and daily activities of the aboriginals of the region. It constitutes the most important photo archive on this subject in Argentina. She was interested in showing the poor living conditions of the aboriginal populations and also highlighting their craft-making skills. Back in Buenos Aires she prepared an exhibition of this work at the Municipal Modern Art Museum of Buenos Aires. She hoped that her photographs would help foster change in the living conditions of the Indians from the Northeast, but this did not happen in her lifetime. A selection of these photographs was shown in 1975 at the Bauhaus Archiv in Berlin and later toured some German cities.

The suicide of her son Andres in 1965 was a profound shock. Her mother had also taken her life, and Grete herself often suffered from depression.

Her teaching activities continued until 1985. Argentine photographer Sara Facio has commented on Stern’s influence in Argentina: “Grete has influenced new generations [of photographers] in two ways. On one hand, with the importance she gives to form. Her photography is not improvised but well thought out. And second by her attitude to life. She is a woman who has been devoted to her vocation, during good times and bad, and young people admire that” (Interview with the author, 1992).

In 1972 Stern traveled to the United States, England, France, Greece and Israel and for the first time since leaving in 1933 she visited Germany. In 1975 the Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin organized the first photographic exhibition after the war, which included Stern’s work. In 1979 Gert Sander, August Sander’s grandson, began representing the ringl+pit work. In 1988 her hometown of Wuppertal organized a ringl+pit retrospective (Emigriert, “Emigrated”) that also included Stern and Auerbach’s later work. And in 1993 the Folkwang Museum in Essen purchased the original negatives and a large body of their work and presented an extensive exhibition of their work. She continued her studio work doing portraits and landscapes until 1980, when she stopped due to failing eyesight. “Photography has given me great happiness. I learned a lot and was able to say things I wanted to say and show,” said Stern in 1992. Grete Stern died in Buenos Aires on December 24, 1999 at the age of ninety-five.

Grete Stern, who started her career in the European avant-garde of the late 1920s, produced her major body of work in Argentina, where her modern and different style placed her among the founders of Argentina’s modern photography.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: studiumiarunicampbr

A publicação da série de fotomontagens de Grete Stern conhecida pelo nome de “Sueños”, realizada para a revista “Idilio” de Editorial Abril, teve início desde seu primeiro número , em 26 de outubro de 1948. Essa publicação introduz uma página “El psicoanálisis le ayudará” na qual Gino Germani, com o pseudônimo de Richard Rest, interpretava sonhos que os leitores descreviam por carta. Foi a própria Grete Stern que propôs a técnica da fotomontagem para ilustrar os comentários.

Realizou um total de 140 fotomontagens, entregando todos os originais à editora. Quando Grete solicitou a devolução tempos depois para os expor, soube que a editora não os havia guardado. Apenas se conservaram quarenta e seis negativos de reprodução dessas fotomontagens, que correspondem quase integralmente ao primeiro ano e meio de publicação.

Na comparação desses negativos com a publicação observa-se que cinco peças foram modificadas posteriormente à publicação e, como sustenta Luis Priamo, “la segunda versión mejora siempre a la primera, y en algunos casos el tipo de modificação ilustra con mucha nitidez el énfasis significativo propuesto por Grete”.

Grete Stern, em “Apuntes sobre fotomontaje”, recorda como se desenvolvia de forma concreta o trabalho dos “sonhos”: “Germani me entregaba el texto del sueño, copia fiel en la mayoría de los casos, de una de las tantas cartas que se habían dirigido a la Editorial Abril. A veces antes de comenzar mi labor, conversábamos con Germani acerca de la interpretação. Por lo general, ocurría que Germani me presentaba solicitudes referidas a la diagramação, que debía ser horizontal o vertical, o con un primer plano más oscuro que el fondo, o representando formas intranquilas. En otras ocasiones me señalaba que tal figura debía aparecer haciendo esto o lo otro; o insistía para que aplicara elementos florales o animales”.

A série dos “sonhos” é a primeira experiência de importância em matéria de fotomontagem em nosso país, e entendemos ser a de maior transcendência. Ela foi exposta em diferentes países da Europa, mas nunca em sua totalidade na Argentina, ainda que muitos dos trabalhos que a compõem sejam altamente conhecidos.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: proaorg

Grete Stern nació en 1904, en una familia de pequeños industriales instalados al nordeste de Colonia, Alemania. Después de su educación secundaria, tomó durante breve tiempo clases de piano y, en 1923, ingresó, para estudiar dibujo y tipografía en una escuela de artes aplicadas de Stuttgart. Trabajó en su ciudad natal como diseñadora publicitaria y realizó dibujos, sobre todo retratos. En 1927 se instaló en Berlín, capital intelectual, además de política, de la república de Weimar, para aprender fotografía. Comenzó tomando clases particulares con Walter Peterhans, pero en 1929 este dejó la ciudad para hacerse cargo de uno de los talleres de esa disciplina en la Bauhaus, una escuela superior de diseño que funcionaba en Dessau. Grete permaneció en Berlín y abrió un estudio de fotografía comercial con su condiscípula Ellen Auerbach. Su actividad se orientó a la fotografía publicitaria, que les permitió ejercer la profesión en forma independiente. En 1932 pudo continuar su formación con Peterhans, pues la Bauhaus se había mudado a Berlín, donde funcionó hasta que fue cerrada por el gobierno nacionalsocialista. Cuando en 1933 ese partido ganó las elecciones y Hitler se convirtió en canciller, decidió huir a Inglaterra: lo hizo a comienzos de 1934, junto con Horacio Coppola, un argentino que había conocido en la Bauhaus, con quien se casó e instaló en Londres. Para Grete -judía y simpatizante de la izquierda intelectual de la república de Weimar- esa emigración forzosa inició la ruptura definitiva con su patria, a la que solo regresó ocasionalmente después de la guerra. A mediados de 1935 la pareja viajó a la Argentina e hizo una exposición de fotografía moderna en los salones de la editorial Sur. Hoy se la considera la primera de ese género en el país. En 1936 el matrimonio se instaló definitivamente en Buenos Aires.

Desde su arribo, Grete se integró decididamente a la sociedad y la cultura de Buenos Aires, a la que contribuyó al traer la visión innovadora de las vanguardias europeas del período entreguerras. Siempre le gustó definirse como una fotógrafa argentina. De hecho, realizó acá su obra más importante, como el conjunto de fotografías que tituló Aborígenes del gran Chaco argentino, un trabajo único y un documento coherente con sus principios éticos y artísticos.

Durante sus primeros años se dedicó sobre todo a retratar artistas plásticos y escritores porteños, tomó vistas de la ciudad y realizó fotomontajes para tapas de libros y revistas. Vivía con sus dos hijos, Silvia y Andrés, en Ramos Mejía, en una casa diseñada por el arquitecto ruso Wladimiro Acosta, uno de los promotores de la arquitectura moderna en el país. Una de las primeras muestras del grupo madi se llevó a cabo en esa casa en 1945. En 1948 inició una serie de fotomontajes que llamó Sueños, elaborados para la revista Idilio.

Entre 1952 y 1953 tomó alrededor de 1500 fotografías del paisaje urbano y las costumbres porteñas, para el libro Buenos Aires (Peuser, 1953), trabajo comparable con el dedicado a los aborígenes del Chaco por la cantidad de fotos, el tiempo que le llevó y los formatos (35mm y 6x6cm). En 1956, Jorge Romero Brest le ofreció organizar y dirigir un taller fotográfico en el museo nacional de Bellas Artes, lo cual aceptó. Permaneció en tal función hasta jubilarse en 1970. Hacia 1985 dejó de trabajar y murió en 1998.