CHARLOTTE POSENENSKE

Prototype for Revolving Vane

source: frieze

Charlotte Posenenske was born in 1930 to a Jewish family. During the war, friends hid her from the Nazis; her father, however, committed suicide to avoid persecution. Shortly after the war she studied art under Willi Baumeister, who taught her about Modernism – which, of course, the Nazis had attempted to obliterate. She became particularly interested in painters who explored the spatial qualities of a pictorial surface, in particular Cézanne and early Mondrian. She travelled to the places where they had lived and made plein air paintings.

Her earliest surviving pictures date from the late 50s and reveal her exploration of contemporary movements such as Informel and Abstract Expressionism. It is interesting that she appeared to be less interested than many of her male colleagues in individual expression, applying the paint with a palette knife to create a greater distance between herself and the painting’s surface.

During the 60s, Posenenske increasingly minimised her use of colour and shapes, indicating landscapes, for example, simply by horizontal lines which denoted the sky and earth. As her interest in Constructivism grew, she began painting a series of simple black ink circles, reminiscent of musical notes. It was during this period that she began her sculptural work and it is greatly to the credit of this exhibition, curated by Konstantin Adamopoulos and Burkhard Brun (the artist’s husband who administers her estate), that it is possible to understand that leap.

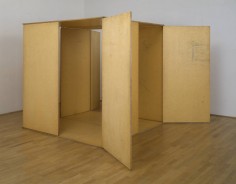

Posenenske applied primary coloured sticky strips to paper, creasing them and then applying them in layers until shapes were built up – as in CMP 65 (1965) for example. She progressed to using sheet metal sprayed with monochrome paint which she then folded into sculptural shapes, and combined this with corrugated cardboard to produce the series ‘Vierkantrohre’ (Square Tubes, 1967) which look like ventilation shafts. She conceived these early sculptures as modules that could be adapted according to available space, each one assembled into a shape ultimately appropriate to the context it found itself in. Anonymity was important to Posenenske. Shifting between Minimal and Conceptual art, she viewed her function as that of a supplier who made material available, but who did not have to be present at the moment of artistic realisation – i.e. at the installation of the pieces in the exhibition space. Gradually Posenenske became increasingly indifferent as to whether or not her creations could be identified as art.

She stopped working as an artist in 1968, no longer believing that art could influence social interaction or draw attention to social inequalities. Instead, she turned her attention to sociology until her death in 1985, becoming a specialist in employment and industrial working processes. She refused to visit any exhibitions during this period, or show her work. There have been a few posthumous exhibitions of her ‘Square Tubes’, mainly in galleries and public spaces. Only now, displayed in the context of her entire artistic output, does her significance to the history of Modernity become apparent.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: hansardgallery

The objects should have the objective character of industrial products. They are not intended to represent anything other than what they are.” Charlotte Posenenske, 1968

Charlotte Posenenske (1930–1985) is one of the key German artists of the 1960s, whose work heralded, along with artists such as Donald Judd, the development of minimalism. This exhibition has been made especially for the John Hansard Gallery and includes the steel constructions – resembling industrially manufactured ventilation ducts – for which she is perhaps best known, alongside Revolving Vanes, paintings, drawings and wall reliefs.

Charlotte Posenenske worked as a theatre stage designer before her artistic career began in the early 1950s. She increasingly turned to industrial materials, creating objects that could be repeated and reconfigured ad inifinitum, and sold her work only at its production value, resisting the conventions of the art market. Despite considerable critical success, the artist felt that she could take this trajectory no further and, in 1968, stopped making art altogether to work as a sociologist.

Since her death in 1985, recognition of Posenenske’s work has been brought to a wider public through major solo exhibitions, including Frankfurt Museum of Modern Art (1990), Taxispalais, Innsbruck (2005), Documenta II, Kassel (2007), Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2010), Haus Konstruktiv, Zürich(2010) and Artists Space New York 2010).

Charlotte Posenenske is a John Hansard Gallery exhibition conceived in collaboration with the executor of the artist’s estate, Dr Burkhard Brunn. A fully illustrated catalogue will be published following the exhibition.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: archivdocumenta12

*1930 in Wiesbaden (DE), *1985 in Frankfurt/Main (DE)

Charlotte Posenenskes work of art consists of objects prepared mostly from industrial materials, sculptures, sculptural pictures and drawings. She pursues a distinct realism of form, of production and distribution, and extended the ranges of concrete-minimal art by adding participative and action-based elements. In parallel to these developments, she also made experimental films in the 1960s. In 1968, Posenenske ended her career as an artist for political reasons and began working as a sociologist.

The Streifenbilder (Stripe Pictures; 1965) are attempts in applying paint in a new way. The diagonal, vertical, and horizontal lines paying homage to the artist group De Stijl she used broad felt-tip pens and narrow chalks. These pieces are well-arranged, clear experiments in colour and composition and thus also experiments in perception. The pictures demonstrate a need to dissolve the orderly hierarchy inherent in painting.

In 1966, Posenenske wrote about her sculptural pictures: They are reminiscent of impressions from our technical environment: Illumination effects, fast driving, spaces of roads and air that narrow, or bulge forward or bend backwards. At the same time, they are a bit reminiscent of our technological environment suggesting parts of automotive chassis, billboards, warning signs whose production is similar in terms of technology.

With Plastisches Bild (Sculptural Picture; 1966) she hints at a three-dimensional form and paves herself a path to objects in real space.