Sylvie Fleury

西尔维·弗勒里

실비 플러

סילבי פלרי

シルヴィ·フルーリー

СИЛЬВИ ФЛЕРИ

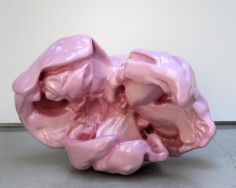

Pink Popcorn

source: landscapeofgirlsblogspot

“Recontextualiser quelque chose de très superficiel lui donne une nouvelle profondeur. Et parfois, juste être une femme, et montrer quelque chose – une paire de chaussures, une voiture ou une œuvre de Carl André – lui donne une nouvelle dimension. ” – Sylvie Fleury

Dans ses œuvres, Sylvie Fleury détourne les objets du quotidien dans des visuels percutants. Ses sculptures s’appuient généralement sur l’exposition d’objets à priori dotés dans la société d’une forte valeur esthétique, sexuelle ou fétichiste mais avec toujours un attachement sentimental : agrandissement de couvertures de “Playboy”, voiture de luxe repeinte en rose, sculptures de rouge à lèvres géants … L’utilisation dans son travail de matières synthétiques comme de la fausse fourrure ou les fortes couleurs rappelle le maquillage féminin, ce qui lui a souvent valu la réputation d’artiste futile et superficielle. Sylvie Fleury revendique son art tout en se présentant elle même comme un sujet de désir, considérant par exemple le shopping comme un acte de plaisir totalement assumé, revendiquant son droit à la consommation et à la beauté. Artiste pop, artiste kitsch, artiste mode, artiste postmoderne, artiste féministe, Sylvie Fleury est un peu tout cela à la fois. Elle engendre la critique, met mal à l’aise le spectateur qui n’a pas forcement l’habitude d’être confronté à un art mettant autant en avant le plaisir de la consommation.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: fashionhr

Švicarka Sylvie Fleury jedna je od najzanimljivijih europskih suvremenih pop umjetnica. Njezine skulpture i medijalne instalacije najčešće direktno provociraju današnji konzumerizam i manično šoping društvo.

U radovima ove talentirane umjetnice može se naslutiti izuzetno puno humora, cinizma i besramnosti, ali i doza oduševljenja New Age-om. Njezine, moglo bi se reći, glamurozne provokacije, obišle su gotovo sve najvažnije svjetske muzejske lokacije i izložbene galerije, a umjetničin rad proširio se i na suradnju s brojnim svjetskim brandovima i modnim magazinima, premda su upravo oni vrlo često indirektan predmet provokacije u njezinim djelima.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: ropacnet

Sylvie Fleury, born in 1961, lives and works in Geneva. She is known for her mises-en-scène of glamour, fashion and luxury products. Although at first glance her works may seem like an affirmation of the consumer society and its values, on closer inspection a more subtle commentary on superficial beauty becomes apparent. Her objects, wall pieces, pictures and installations assume an intrinsic value far exceeding the mere affirmation of brand names. Sylvie Fleury’s bronze sculptures always demonstrate detailed knowledge of the artistic aesthetics of Pop Art and Minimal Art, without her work developing into Art on Art. No artist has probably ever combined the idea of Duchamp’s Ready Made with Warhol’s affirmation of the consumer world in such an unbiased way. In Fleury’s sculptures, the profane assumes an aura of sanctity.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: contemporary-magazines

At heart we are all fetishists. We’re obsessed with objects, whether spiritual, magical, sexual or merely material. It is what defines us and what we create. Sylvie Fleury’s work is a manifestation of the human need to worship, just as sexual fetishes convey the necessity of fulfilment. She works with objects that embody sexuality, idolatry and obsession to underline our fixations. The shopping sprees, the out-of-this-world cars, the goldness of everything: it’s a glimpse of fantastic excess that crosses the boundaries of illusion and reality.

For someone who made her name with installations of Chanel shopping bags, Gucci heels and crushed American classic cars, Fleury is decidedly disinterested in pointing out the evils of commodity and consumption. She has much more to say about art than mere exposure of the banality of fashion and shopping: ‘I don’t really care, since I believe that the issue has been tiresomely investigated since the eighties. One can consume art or experience it in thousands of ways; it’s all a matter of bowels, bladder and sometimes brains.’ In pieces like her bronze Alaia Shoes (2003) there’s more love than hate of the object. She plays with fashion’s fetishisation of touch, shapes and labels, aware of its cryptic meanings and nuances. She‘s amused by the rules and absorbed in them. ‘Any fetish relies on codes, on a system of codes; these will be shared by speciality groups. Art has always relied on similar patterns. Fashion draughts the same structure in an even more obvious way. It’s clear that I happen to use one for another.’ Shopping and fashion are equally the language, medium and subject of the work.

The removal between the viewer and Fleury’s art object is more acute than the distance between shopper and commodity in the shopping environment. We are not supposed to touch the installations, making the moment of ‘buying’ even more distant, the labels even less attainable. It’s a tension that Fleury exaggerates and exploits. ‘[It’s] the paradox in the commodity factor… Even when you get it, you don’t get much.’ She often plays on this emptiness, this lack. Pieces like CHANCE (2003), a gold plated empty shopping basket, and ELA 75/K, Easy, Breezy, Beautiful (2000), an empty gold shopping trolley on a spinning mirrored pedestal, idolise the moment of purchase while highlighting its barrenness.

Fleury’s use of the pedestal flirts with western society’s structures of power, value and beauty, transforming the objects into something of worship yet creating an undercurrent of superficiality. Her modes of display are camp, superficial, venerated and exalted all at the same time; she seems to be mocking the viewer and the very act of encountering art. In her latest show at the Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Fleury is showing what she describes as weird fountains in ceramic in the shape of tyres. ‘I might add to the sound of the water and little smoke, some coloured lights inside the pedestals and some soft relaxing music,’ she muses before installation. The gold-plated tyres are to be exhibited on transparent Plexiglas pedestals in a room painted deep blue. It’s a pop nudge against modernism: Duchamp’s Fountain (1917/64) as a kitsch dimestore amalgam surrounded by Yves Klein blue. Similarly her giant gold cages bring to mind Duchamp’s Why Not Sneeze Rose Selavy? (1921) from which all the sugar cubes have flown. Rather than a surreal bird cage, Fleury’s giant pens resemble the enclosures of a high-class human zoo. They question objectification and containment, again highlighting the emptiness at the heart of ownership, purchase and even viewing.

Fleury’s chroming technique superficially fetishises the object in a Liberace-plays-Las Vegas vision of beauty and prestige. Using superficially ‘female’ gold sheen and pink gloss she is reappropriating the power of glamour, high heels and hot pink. In a way she reappropriates fetish itself: ‘Because the tools of power are largely actioned in our society by males rather than females, it just happens that, for instance, any fetish is first seen through the realm of men, and that’s commonly taken as granted.’

Fleury’s fetish-filled world is transformed through a female gaze. In a recent conversation with artist Peter Halley, she explained: ‘Just recontextualising something that’s very superficial will give it a new depth. And sometimes, just being a woman and showing something like a pair of shoes, a car, or a Carl Andre gives it another dimension.’ Her ‘feminisation’ of typically ‘masculine’ objects has a tongue in cheek political edge. Pieces like Skincrime2 (Givenchy 601) (1997), a crushed car painted in pink nail varnish, and the painted slogan Miniskirts are back (2003) seem to giggle at tired presumptions, with knowing humour.

Rather than condemning the rigid genderisation and ideological constructs within the imagery and language of fashion magazines, Fleury reclaims it. The pink neon italics of Perpetual Bliss (2003) or ‘C’est La Vie!’ written on a pink wall exaggerate and enlarge the superficial vision of gender-specific language to iconic levels.

There is a petulant, dominant edge to Fleury’s work that reeks of flirtation. She teases the viewer with colour and easy and immediate objects and imagery, which comes to the fore in her video work. Her latest video piece is in two parts; the first, Here Comes Santa (2003), shows the legs and high heels of a woman destroying the Christmas baubles laying around on a red carpet; the second, Bells (2003), shows the same process on a green carpet. ‘The person walks the carpets until no ball is left in one piece, some parts are quite violent and the soundtrack mixes Christmas music with very loud sounds of the balls being smashed.’ The work is visually and aurally piercing and violent, while the extremely high stiletto mules smashing and crunching the mirrored balls present a cliché of female sexual power, as if the woman is stamping her feet for recognition.

Fleury’s recent multiples play with similar ideas. Deep & Dark is a series of feather boas inside long, narrow Plexiglas boxes in what she calls ‘an erect hanging position’. They explore powers of seduction and delicacy while illustrating the containment of femininity and the clash of male and female sensibilities. Whereas Meret Oppenheim’s fur-covered tea cups Breakfast in Fur (1936) unnerve because of the accessibility of the tactile material, here Fleury’s boas are frustrating because they cannot be touched.

For Fleury fetish and seduction are more about power and control than something solely sexual. ‘Strategies of seduction are infinite. It’s debatable that inert objects actively produce seduction,’ she observes. ‘One could argue that seduction is a reverse power game where the seducer aims at controlling the realm that will over-power him in return.’ You get the feeling that Fleury is always in control of her seduction methods; she knows what she wants and how to get it, but isn’t immune from temptation herself. She adds wryly, ‘Many artists are basically seduced by their own work, whatever that implies…’

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: socksandsandals-mag

Los objetos de la artista Sylvie Fleury tienen un color brillante y un aspecto lacado. Sus carritos de la compra áureos, zapatos de tacón plata y bolsos de dimensiones insospechadas proponen una reflexión sobre la relación del consumidor con los objetos, así como la seducción, la superficialidad y el acto mismo del consumo.