Félix González-Torres

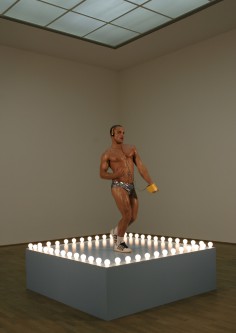

Go Go Dancing Platform

source: emnomedosartistasorgbr

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1957, Guaimaro, Cuba – 1996, Nova York.

Para Felix Gonzalez-Torres, a arte deveria ser uma expressão colaborativa entre espectador e artista. Nesta parceria, os espaços expositivos de museus e galerias deixam de ser exclusivamente de contemplação. O artista considera seus trabalhos como propostas de vivências e negociações, em torno das quais, o público pode compartilhar reflexões sobre arte, política, identidade, sexualidade e coletividade.

Obra e espectador se unem numa performance que pretende expurgar a dor da perda de seu companheiro, morto em decorrência do vírus da AIDS. Gonzalez-Torres transgride as indicações rigorosas dos espaços expositivos e incentiva o público a participar da obra, porque somente comendo as balas a obra acontece. É como se cada pessoa que retirasse uma bala levasse um pedaço do corpo do casal.

Gonzalez-Torres desafia a autoridade dos espaços expositivos quando propõe que o público deve participar da obra retirando um cartaz e fazendo dele o que bem entender. Desta maneira, o próprio artista degrada a ideia de originalidade do trabalho, o que pode também atestar a redução do seu “valor artístico”.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: guggenheimorg

Felix Gonzalez-Torres was born in Guáimaro, Cuba, in 1957. He earned a BFA in photography from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, in 1983. Printed Matter, Inc. in New York hosted his first solo exhibition the following year. After obtaining an MFA from the International Center of Photography and New York University in 1987, he worked as an adjunct art instructor at New York University until 1989. Throughout his career, Gonzalez-Torres’s involvement in social and political causes as an openly gay man fueled his interest in the overlap of private and public life. From 1987 to 1991, he was part of Group Material, a New York-based art collective whose members worked collaboratively to initiate community education and cultural activism. His aesthetic project was, according to some scholars, related to Bertolt Brecht’s theory of epic theater, in which creative expression transforms the spectator from an inert receiver to an active, reflective observer and motivates social action. Employing simple, everyday materials (stacks of paper, puzzles, candy, strings of lights, beads) and a reduced aesthetic vocabulary reminiscent of both Minimalism and Conceptual art to address themes such as love and loss, sickness and rejuvenation, gender and sexuality, Gonzalez-Torres asked viewers to participate in establishing meaning in his works.

In his “dateline” pieces, begun in 1987, Gonzalez-Torres assembled lists of various dates in random order interspersed with the names of social and political figures and references to cultural artifacts or world events, many of which related to political and cultural history. Printed in white type on black sheets of paper, these lists of seeming non sequiturs prompted viewers to consider the relationships and gaps between the diverse references as well the construction of individual and collective identities and memories. Gonzalez-Torres also produced dateline “portraits,” consisting of similar lists of dates and events related to the subjects’ lives. In Untitled (Portrait of Jennifer Flay) (1992), for example, “A New Dress 1971” lies next to “Vote for Women, NZ 1893.”

Gonzalez-Torres invited physical as well as intellectual engagement from viewers. His sculptures of wrapped candies spilled in corners or spread on floors like carpets, such as “Untitled” (Public Opinion) (1991), defy the convention of art’s otherworldly preciousness, as viewers are asked to touch and consume the work. Beginning in 1989, he fashioned sculptures of stacks of paper, often printed with photographs or texts, and encouraged viewers to take the sheets. The impermanence of these works, which slowly disappear over time unless they are replenished, symbolizes the fragility of life. While in appearance they sometimes echo the work of Donald Judd, these pieces also belie the Minimalist tenet of aesthetic autonomy: viewers complete the works by depleting them and directly engaging with their material. The artist always wanted the viewer to use the sheets from the stacks—as posters, drawing paper, or however they desired.

In 1991 Gonzalez-Torres began producing sculptures consisting of strands of plastic beads strung on metal rods, like curtains in a disco. Titles such as Untitled (Chemo) (1991) and Untitled (Blood) (1992) undercut their festive associations, calling to mind illness and disease. In 1992 he commenced a series of strands of white low-watt lightbulbs, which could be shown in any configuration—strung along walls, from ceilings, or coiled on the floor. Alluding to celebratory décor—in the vein of the charms of outdoor cafés at night—these delicate garlands are also a campy commentary on the phallic underpinnings of numerous Minimalist creations, particularly Dan Flavin’s rigid light sculptures. Also in 1992, Untitled (1991), a sensual black-and-white photograph of Gonzalez-Torres’s empty, unmade bed with traces of two absent bodies, was installed on 24 billboards throughout the city of New York. This enigmatic image was both a celebration of coupling and a memorial to the artist’s lover, who had recently died of AIDS. Its installation as a melancholic civic-scaled monument problematized public scrutiny of private behavior.

Gonzalez-Torres received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1989 and 1993. He participated in hundreds of group shows during his lifetime, including early presentations at Artists Space and White Columns in New York (1987 and 1988, respectively), the Whitney Biennial (1991), the Venice Biennale (1993), SITE Santa Fe (1995), and the Sydney Biennial (1996). Comprehensive retrospective exhibitions of his work have been organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (1994); Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1995); Sprengel Museum Hannover, Germany (1997); and Biblioteca Luis-Angel Arango, Bogotá (2000). Other exhibitions have been held at the Hamburger Bahnhof-Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin (2006–07); PLATEAU, Seoul (2012); and Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul (2012). A survey of his work, Specific Objects without Specific Form, was organized by WIELS, Centre d’Art Contemporain, Brussels (2010), and then traveled to the Fondation Beyeler, Basel (2010), and the Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main (2011). In 2007, Gonzalez-Torres was selected to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale in the exhibition Felix Gonzalez-Torres: America. He died in Miami on January 9, 1996.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: queerculturalcenterorg

Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1957-1996)

In 1993, in lieu of a standard biography/bibliography, Felix chose to write a portrait of himself. This is the Biography that we have chosen to print, which is in the true spirit of this gifted artist.

1957 born in Guaimaro, Cuba, the third of what would eventually be four children 1964 Dad bought me a set of watercolors and gave me my first cat 1971 sent to Spain with my sister Gloria, then went to Puerto Rico to live with my uncle 1979 returned to Cuba to see my parents after an eight-year separation 1981 parents escaped Cuba during Mariel boat lift, my brother Mario and sister Mayda escaped with them 1978 met Jeff in Puerto Rico 1976 Gloria and I moved to our own apartment-small, but full of sunlight 1977 Rosa 1976 met my friend Mario 1979 moved to New York City 1980 met Luis at the beach 1983 received BFA from Pratt Institute 1981 and 1983 attended the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program 1987 received MFA from the International Center of Photography and New York University 1983 Ross at the Boybar 1985 Jeff gave me Pebbles and Biko, two Lilac Point Siamese cats-hardly able to support myself, and now with two cats to feed, only Jeff 1985 first trip to Europe, first summer with Ross 1986 summer in Venice, studied Venetian painting and architecture 1986 blue kitchen, blue flowers in Toronto – a real home for the first time in so long, so long, Ross is here 1987 Wawanaisa Lake: beavers, wild brown bears, Harry retrieved every buoy he sees, New York Times every morning, duck cabin 1986 Mother died of leukemia 1990 Myriam died 1991 Ross died of AIDS, Dad died three weeks later, a hundred small yellow envelopes of my lover’s ashes-his last will 1991 Jorge stopped talking to me, I’m lost – Claudio and Miami Beach saved me 1992 Jeff died of AIDS 1990 silver ocean in San Francisco 1992 President Clinton – hope, twelve years of trickle-down economics came to an end 1990 moved to L.A. with Ross (already very sick), Harry the Dog, Biko, and Pebbles, the Ravenswood, Rossmore, golden hour, Ann and Chris by the pool, magic hour, rented a red car, money for the first time, no more waiting on tables, ‘Golden Girls’, great students at CalArts, Millie and Catherine, went back to Madrid after almost twenty years-sweet revenge 1989 the fall of the Berlin Wall 1991 Bruno and Mary, two black cats Ross found in Toronto, came to live with me 1991 the world I knew is gone, moved the four cats, books, and a few things to a new apartment 1991 went back to L.A., hospitalized for 10 days 1990 first show with Andrea Rosen 1993 moved to 24th Street 1987 joined Group Material 1991 Julie moved from Brooklyn to Manhattan 1992 the forces of hate and ignorance are alive and well in Oregon and Colorado, among other places 1993 Sam Nunn is such a sissy, peace might be possible in the Middle East 1992 started to collect George Nelson clocks and furniture 1993 three years since Ross died, painted kitchen floor bright orange, this book.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: culturacolectiva

El trabajo de González-Torres habla, prácticamente, de tres temas: muerte, amor y luto. Puede sonar banal y su obra parecer casi improvisada, pero el discurso impecable y conmovedor detrás es lo que le da la fuerza para seguir impactando a generaciones.

Félix González-Torres nació en Cuba, en 1957, y se mudó de país en país, hasta instalarse, finalmente, en Puerto Rico, en la universidad de ese país estudió arte. Allí consiguió una beca para irse a Nueva York y es en esa ciudad donde consolida su carrera, al cosechar éxitos importantes en el mundo del arte.

La homosexualidad abierta de González-Torres jugó un papel importante en su producción, aunque, como él mismo dijo en una entrevista, su arte no es arte gay sino que es arte que habla del amor por un hombre. Se refiere particularmente a la historia de amor de ocho años que vivió con su compañero Ross Laycock, quién murió de SIDA cinco años antes que el artista.

Ese suceso incide fuertemente en la producción artística de González-Torres, quién siempre consideró que el público para el que hacía arte era exclusivamente Laycock. Durante el año de su muerte, en 1991, González-Torres creó una serie de obras para homenajear a su pareja y trabajar su luto.

Una de las más conocidas es Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), en la que una montaña de caramelos envueltos en celofán de distintos colores es libremente colocada en el espacio donde se expone.

González-Torres sugiere que la cantidad de caramelos expuestos pese exactamente 175 libras, que era el peso de Ross. La acción que realiza el público al toma caramelos y hace disminuir el tamaño de la obra es equiparado a la pérdida de peso y al sufrimiento que vivió Ross antes de morir; como si desapareciera. El espacio expositor se compromete a renovar las 175 libras de caramelos en cuanto se terminen, esto como una manera de prolongar su “existencia”. Asimismo, la acción de cada espectador al ingerir el dulce es comparable con el acto católico de la comunión, en el que se recibe el cuerpo de Cristo. Quizá, González-Torres buscaba reproducir la esencia de Ross a través de cada espectador.

Untitled (Perfect Lovers) es otra de sus obras, producida durante el mismo año, que reflexiona sobre la enfermedad y el luto. El artista expone dos relojes de cocina idénticos, sincronizados exactamente a la misma hora, uno junto al otro. Los dos relojes marcan los segundos al compás, día tras día. Pero con el tiempo, poco a poco, empiezan a perder sincronía hasta que el tiempo entre ellos crece y los separa cada vez más.

Durante el mismo año, y como homenaje a Ross, Félix expuso veinticuatro espectaculares en las calles de Nueva York que presentaban la misma imagen: la fotografía de una cama deshecha y con la impresión de dos cuerpos que estuvieron recientemente allí. El número de carteles corresponde con la fecha de la muerte de su compañero y no van acompañados ni de firma ni de didascalía. La ausencia de los cuerpos refleja el duelo por la pérdida, pero, también, se traduce en una declaración política y social para el ambiente de la época: “esconder” un cuerpo homosexual que padeció SIDA y que ha dejado su huella, no deja de ser controversial.

En 2010 se realizó una retrospectiva de la obra de González-Torres en el Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC), en el Distrito Federal, curada por Sonia Becce. Próximamente se podrá ver algo de su obra en la exposición panorámica / paisajes, 2013-1969 que inaugura estos días en el Palacio de Bellas Artes.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: fluctuatpremierefr

Félix González Torres, artiste américain d’origine cubaine, a su placer l’émotion au coeur de l’art conceptuel, en faisant de son oeuvre un acte de transmission. Le Wiels, à Bruxelles, propose une rétrospective majeure de l’artiste, mort des suites du SIDA en 1996.

Un rideau de perles à traverser, des bonbons ou des feuilles de papier mis à la disposition du visiteur, deux horloges parfaitement accordées ({Perfect Lovers}), la photographie d’un oiseau en plein vol morcelée en puzzle, ou une autre enclose dans une bouteille, comme un SOS, des guirlandes d’ampoules qui évoquent l’ambiance de fêtes de village, des fortune cookies, ces biscuits à ouvrir que l’on donne dans les restaurants chinois aux Etats-Unis et qui, ici, délivrent tous une prédiction bienveillante… L’art de Félix González Torres est une suite d’éblouissantes variations sur le pouvoir de l’art à créer du lien entre les êtres, dans un processus d’activation des oeuvres que l’on peut assimiler à des sortes de rituels de communion.González-Torres, né à Cuba en 1957, grandit à Puerto Rico, puis passe son adolescence en Espagne, avant de s’installer à New York à la fin des années 1970. Influencé par l’art minimal et l’art conceptuel qui, selon lui, « {en demande tant au public, tant de participation, tant d’implication intellectuelle} », il trouve cependant une voie originale en instillant dans sa réflexion sur l’image, le langage et la forme un rapport à l’humain qui provient de la confusion entre l’intime et le public, l’intérieur et l’extérieur, l’éphémère et le durable. Ainsi lorsqu’il offre des bonbons (les {Candy Stacks}), posés à même le sol en tas régulièrement réapprovisionnés, la dispersion de l’oeuvre dans le corps même des visiteurs en révèle l’extrême fragilité et en même temps la pérennise par sa propagation presque infinie, tout en faisant écho, symboliquement, à la contamination du SIDA, qui toucha l’artiste ainsi qu’un grand nombre de ses proches.De même, la fameuse guirlande d’ampoules, qui est avec les {Candy Stacks}, l’une des oeuvres emblématiques de Félix González-Torres, nécessite, comme au chevet d’un convalescent, une attention de tous les instants. Si l’artiste, dans son statement, laisse entièrement libre au curateur ou au collectionneur de l’oeuvre la disposition de la guirlande bouleversant par là-même le statut de l’auteur, dans la lignée de l’art conceptuel , il impose comme contrainte que toutes les ampoules fonctionnent en même temps… Si l’une d’elles est éteinte, l’oeuvre est systématiquement désactivée : métaphore de la solidarité, elle fonctionne comme un tout, son essence résidant dans chacune de ses parties. L’exposition du Wiels, par la sobriété de la mise en scène des objets, que l’on doit à la jeune curatrice américaine Elena Filipovic, rend un hommage d’autant plus émouvant à l’oeuvre d’un artiste essentiel de la fin du XXe siècle. Ainsi au dernier étage de l’institution bruxelloise, sur le papier argenté de friandises disposées en rectangle régulier, comme une immense stèle étincelante, vient se refléter la lumière du ciel qui inonde la pièce, et éclairer des mots inscrits au mur. Ultime oeuvre de l’artiste, cette succession de mots et de dates ({Bay of Pigs} 1961, {Black Monday} 1987, {A view to remember} 1995) mêle les événements intimes de la vie de González-Torres à ceux de la grande Histoire. Pour l’artiste, ils sont tous intimement mêlés, et forment ainsi une manière d’autoportrait. Libre au spectateur de reconstituer le puzzle.