ALAIN BUFFARD

INtime / Extreme

source: alainbuffardeu

Il vit et travaille en France.

Alain Buffard commence la danse en 1978 avec Alwin Nikolais au Centre national de danse contemporaine d’Angers. Interprète de Brigitte Farges, Daniel Larrieu ou Régine Chopinot, il devient assistant à la Galerie Anne de Villepoix et couvre l’actualité des arts visuels en France pour pour deux quotidiens norvégiens.

En 1996, il fait deux rencontres déterminantes, Yvonne Rainer et Anna Halprin avec qui il travaille en tant que lauréat de la “Villa Médicis – hors les murs”.

L’association pi:es est fondée en 1998. Depuis sa création, ce sont 14 productions (créations chorégraphiques, films, installations videos) qui tournent de part le monde: Centre Pompidou-Paris, Montpellier Danse, Les Subistances-Lyon, Arsenic-Lausanne, Fondation Serralves-Porto BIT-Bergen, Festival d’Athènes, Festival Panorama-Rio de Janeiro, DTW-New York…

Il est co-commissaire de l’exposition Campy, vampy, tacky à La Criée-Rennes en 2002. Artiste professeur invité au Fresnoy pour la saison 2004/2005, il présente l’exposition Umstellung/Umwandlung à Tanzquartier-Vienne en 2005. En 2013 à Nîmes, il conçoit un projet original mêlant commissariat d’exposition, programmation spectacle vivant et conférences autour des questions de territoire et de représentation.

Alain Buffard était artiste associé au Théâtre de Nîmes pour les saisons 2010-2011 et 2011-2012. L’association pi:es est conventionnée par la DRAC Languedoc-Roussillon et la Région Languedoc-Roussillon.

________________________________________________________________________________

1988, Bleu nuit, solo

1989, Les Maîtres Chanteurs de Wagner, mise en scène Claude Régy au Théâtre du Châtelet

1998, Disparus, séquence de long métrage de Gilles Bourdos (Quinzaine des réalisateurs à Cannes)

1998, Good boy, solo au festival

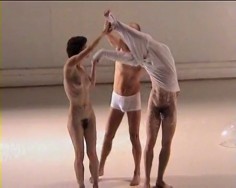

1999, lNtime / EXtime et MORE et encore, avec Alain Buffard, Matthieu Doze, Anne Laurent et Rachid Ouramdane

2001, Dispositifs 3.1, avec Alain Buffard, Anne Laurent, Laurence Louppe et Claudia Triozzi

2001, Good for… créé à partir des matériaux de Good boy, avec Alain Buffard, Matthieu Doze, Rachid Ouramdane et Christian Rizzo

2001, Des faits et gesttes défaits, film vidéo réalisé pour la Villa Gillet-Lyon

2002, Dé-marche, coréalisé avec l’artiste visuel Jan Kopp, avec Alain Buffard, Jan Kopp et Laurence Louppe

2002, Campy, vampy, tacky, exposition au centre d’art contemporain La Criée-Rennes, co-commissariat avec Larys Frogier

2003, Wall dancin’ / Wall fuckin’, avec Alain Buffard et Régine Chopinot

2003, Mauvais genre, 3ème version de Good boy pour une vingtaine de chorégraphes

2004, My lunch with Anna, film avec et autour de Anna Halprin

2005, Les Inconsolés, avec Alain Buffard, Matthieu Doze et Christophe Ives

2005, Umstellung/Umwandlung, exposiiton à Tanzquartier-Vienne commanditée par le Siemens Arts program

2007, (Not) a Love Song, avec Miguel Gutierrez, Vera Mantero, Claudia Triozzi et Vincent Ségal

2008, EAT, installation vidéo avec Sebastien Meunier

2009, Self&others, avec Cécilia Bengolea, Fançois Chaignaud, Matthieu Doze et Hanna Hedman

2010, Tout va Bien, avec Lorenzo de Angelis, Armelle Dousset, Hanna Hedman, Jean-Claude Nelson, Olivier Normand, Tamar Shelef, Betty Tchomanga, Lise Vermot

2012, Baron Samedi, avec Nadia Beugré, Hlengiwe Lushaba, Dorothée Munyaneza, Olivier Normand, Willl Rawls, David Thomson, et les musiciens Sarah Murcia et Seb Martel

2013, Histoires parallèles: pays mêlés, événement conçu à Nîmes autour des questions de territoires et d’identité (exposition, spectacle vivant, conférences, rencontres, projections)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: alainbuffardeu

Born and lives in France.

Alain Buffard starts dancing in 1978 with Alwin Nikolaïs at the Centre national de danse contemporaine in Angers. He dances in several productions from Brigitte Farges and Daniel Larrieu, as well as Régine Chopinot, Philippe Decouflé. He

realizes a choreography for two plays with Marie-Christine Georghiu, accompanied by the Rita Mitsuko rock group, a first solo Bleu nuit in 1988, and Wagner’s Master singers of Nuremberg staged by Claude Régy in 1989.

While carrying on his career of dancer, he works as an assistant in Anne de Villepoix ‘s Gallery for exhibitions on R. Zaugg, Fischli & Weiss, Chris Burden and V. Acconci. At the same time, he is a correspondent for two Norwegian daily papers, for which he covers visual arts events in France.

He stops dancing between 1991 and 1996. In 1996 he makes two decisive meetings :

one with Yvonne Rainer on the occasion of the updating of her play Continuous Project Altered Daily by the Albrecht KNUST Quatuor, and another one with Anna Haplrin, with whom he is working as the winner of the “Villa Medicis – hors les murs” prize.

In January 1998 he creates Good boy, his second solo, and then makes in 1999 two trios INtime / EXtime and MORE et encore. During a residency at Espace Pier

Paolo Pasolini in Valenciennes in 2001, he presents Dispositifs 3.1, and creates Good for…, revival of Good boy for four dancers, and then a video film, Des faits et des gestes défaits. In 2002 he realizes Dé-marche with the visual artist Jan Kopp and becomes co-curator with Larys Frogier for the exhibition Campy, vampy, tacky at the centre of contemporary art La Criée in Rennes.

In 2003, he elaborates Wall dancin’ – Wall fuckin’, a duo with Régine Chopinot, and Mauvais genre, third revival of Good boy for 20 dancers-choreographers. He creates Les inconsolés, a trio with Matthieu Doze, Christophe Ives and himself,

in January 2005. In April 2005, he presents Umstellung Umwandlung, an exhibition for a theater at Tanzquartier in Wien in collaboration with Siemens Art Program.

In June 2007 he creates (Not) a Love Song ( with Miguel Gutierrez, Vera Mantero, Claudia Triozzi and Vincent Ségal).

In 2008, he realized EAT, a video installation with Sebastien Meunier and Self&others at “la Ménagerie de Verre”.

Tout va bien, Alain Buffard’s new piece (premiered in June 2010 at Festival Montpellier Danse), is starting its tour now.

He also realized My lunch with Anna, a film with Anna Halprin in California with the help of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in France and le Fresnoy ? national studio for contemporary arts, where he was associated artist during the season 2004-2005.

There is a Buffard style, of course. Out of the box. Totally indefinable. Alternately cheeky, tender, scathing, droll and alarming, his works introduce us to a singular universe as well as giving us a sensitive perspective on the world.

The universe of Alain Buffard

Certainly it would be possible to analyse the oeuvre of Alain Buffard based entirely on Good Boy, his first piece, a plausible matrix for the works that followed 1. Here we find the genesis of his themes, later they are split into so many variations, becoming independent choreographic works, echoing each other, bouncing off each other. Take the conspicuously memorable scenes in Good Boy, like the one where the cast is putting on layer after layer of jockey shorts or the declensions punctuating the developmental path of the choreographer (Good For, Mauvais genre), woven into other plotlines, other arrangements. There is the naked body, in its simplest, purest sense as an “apparatus”, treated as if it were no more than a subtle machine, and we examine each movement, using the medicine boxes as twisted “high heels,” or the somewhat confusing exploration of sex which incongruous hands unfurl in order to find defunct sensations and elements

we will find scattered, parsed and readjusted, parts of other works. In this fashion, the “training” suggested by the title of “Good Boy” will become the fundamental subject of Dispositif 3.1, relayed by an imperious voice calling out, “good, my little girl,” to three manifestly false little girls who are supposed to learn how to stand — by crawling.

“You can do it,” encourages the voice. Alain Buffard says the same thing, not without a certain humour, to Régine Chopinot in Wall dancin¹- Wall fuckin¹: “you can do it!” However, this kind of game of hide and seek really teaches us something important for Alain Buffard, dance is about the art of displacement, among other things.

Especially in terms of interpretation.

And with the sensual pleasure that this kind of interpretation involves: skimming through the possibilities yet choosing none of them, twisting the idealised form in order to force the “repressed” form to emerge, altering, reshaping a movement or an idea sometimes even through its transmission.

It¹s his work, or in other words, a way of bringing a shape to, literally embodying something which does not yet exist, which is still at the thinking stage. A corporeal translation of that which happens elsewhere, on a different stage when language

commands it.

In truth, Alain Buffard works with the raw material of choreography. And what exactly is that? That which gives substance to its performer, intent to a movement, and lots to think about to its audiences.No doubt this is what distinguishes him from other choreographers who are merely looking for movement material. Perhaps it is left over from his past as a dancer — he left the field because he was tired of only ³adding movement to other movements, ² quoting the critic and writer Laurence Louppe in Dispositif 3.1.

So there is indeed a Buffard style, a sort of trademark, having to do both with the restraint of his spare yet complex sets, the pertinence of his musical and production sound choices, or the recurring presence of certain elements. Blank space as well as the lighting affect pictoral values, modulating and modifying them as much as the bodies working in them, generating images and shadows. And the shadows of those shadows, almost mental projections, superimposed so that they cloud the spectator¹s vision or bring out the real ghosts, those that haunt the edges of our dreams.A way of showing the bodies. Horizontals and diagonals channel the rhythms of dance, alternating bodies at once glorious and bereft, feelings of rage and tenderness, positions both standing and lying down. An often acerbic sense of humour which knows how to set up its confrontations with the system dominating it. With a dazzling wit. Then there are the heels. The spike heels — which give us a hint, a flavour, triumphant or shaky, worn both by very bad boys and femmes fatales.

For example, each work, be it Good Boy or Self & Others has its own world, but somehow its universes seem to be from the same nebula, bringing us into a multiplicity of points of view for the astute observer who is willing to adjust his or her vision and attempt to interpret that which is happening in plain sight.

Tracking Alain Buffard

DanceEssential, it is the raw material of each of his works, the common denominator of the themes of those works. This idea nags at the dancer, as it is approached from the inside. With the bizarre and unsettling relationship it creates with the body of the person performing it, a kind of identititary blur which touches on identity, sex, food, the order of things. In Good Boy, the body learns while it is dancing.

Images itself. Finds its animality. Sparking a rush of chimeric images, metamorphosing the body into a wounded animal, the sign of a power gone forever, or into a companion animal to be cajoled or led around on a leash. Or it falls apart in an excess of detail (Good Boy, INtime EXtime, More et encore). As if, by working with each limb, each muscle and tendon, its material integrity melts away, resulting in the dancer¹s loss of identity, all metaphors which evoke the strangeness of the body as it is

transformed by dance, or by what happens at each stage of the movement up to letting it go. Wall dancin’- Wall fuckin’ recycles the question: after having literally circled around the word dance, the piece ends with “it¹s not me,” while

a man (Alain Buffard) and a woman (Régine Chopinot) are dancing, naked, like the final act reuniting two bodies separated by a wall. Who is dancing, then? What do we see when we are looking at dance? More to the point, what are we coming to see?

Sex

To replace or to question sexual elements in dance is considered very “politically incorrect”

-it is one of the unspoken rules of choreographic style. For some, it has probably made Alain Buffard one of those “disturbing” choreographers, since each choreographic act in France is based on a strategy of sexual avoidance and the resisting of impulse. However, far from provocation, what is sexual with Alain Buffard is an invitation to look differently

at the body, which is completely itself and does not try to sidestep either the erotic or eroticism itself. In so doing, he exposes his own sexuality while wiping away the contours of a given sexual identity. Nudity for him is not neutral but astonishing.

We may see palpations or massages, fantasy or phantom embraces, suggestive poses, unnerving movements, unnameable desires are scattered through his work. Buffard shows us much more than just skin, the raw flesh of beings rendered fragile by the gaze of others, but who go for it anyway. Les Inconsolés (The Inconsolable), is rightly seen as a major, courageous work which goes beyond its face value, daring to speak of the “ravishing” and of the confusion of desire in a sort of new theatre of cruelty which could be about childhood as well as about the worst atrocities.

Gender

Bewigged female symbols, drag queens wearing “shoes” of retrovir medicine boxes or six-packs of mineral water, imaginary movie stars awaiting their comeback the men and women who appear in the works of Alain Buffard are uncertain, their loyalty somewhat risky. For an instant something happens, challenging the official distinction between individuals. Going beyond the question of sexual choice, the interrogation of gender in his works overflows the border between masculine and feminine in order to consider the roles assigned to each. This problem, the impossibility of recognising oneself in the mirror held up by society the “other” is more of a woman, more French, whiter than we are this is what every minority must feel. He chooses to show us beings who are always out of place, with this essential doubt, never closed off where

intrinsic certainty still trolls. Perhaps the dancer is really of a third sex, an indeterminate being who cannot identify with him- or her-self and who refuses to separate the anatomical body from its imaginary one?

The BODY

Régine Chopinot: “I¹d like to do a real dance.”

Alain Buffard: “Body.”

[…]

Régine Chopinot: “Don¹t forget that it must be very very pretty!”

This dialogue, an excerpt of Wall dancin’ Wall fuckin’ represents fairly how Alain Buffard feels about the body, which cannot be separated from its use in dance as the body we see is inevitably the body of a dancer he aims to counteract the image of the glorious body vaunted by the dance world and by the time in which we live. In society today the body has become a new fetish object, a perfect tool for performing all the virtuosities which bring us back to the question of invulnerability of the body and its counterpart:

keeping death at a certain distance. Alain Buffard was one of the first choreographers to actually address the existence of AIDS in dance (Good Boy), updating this corporeal problem which strikes at the very heart of dance and forces it into view. If the body, the dancing body is the symbol of the visibility of life, it is also the carrier of that invisible death which surreptitiously ticks away inside it. The body we see developing in the works of Alain Buffard really moves, literally plunging into its own organicity, irradiating and overflowing its physical envelope. It is formed both by burying and by tearing away its own parts. The voice becomes an organ, the skin is rendered more visible by the sound of fondling, of its hitting the floor, the wall, its silhouette distorted by prostheses or dismembered by its movements, food which is ingested, disgorged,

regurgitated — so many scenes which bring a carnal, political dimension back to the corporeal, since this desublimation allows one to resist a submissiveness which has become more intimate as society seeks to create a new myth, a superman.

TRAINING

Following the implacable logic of that which comes before, it is not surprising that apprentissage or training from the point of view of the dancer, the dressage of bodies, is one of the recurring themes of the choreographer. Horribly funny, it is often perceived as a failure of the coercion employed by he who has the power: the choreographer, the parents, the institutions … Each time the impossibility of conforming to the norm wins out, by a hair or by default. The hysteria of the link is denounced each time. Like the little girls in the wigs in Dispositif 3.1 who try desperately to reproduce while on all fours

a movement shown by someone who is standing, literally “showing” it. And the exchange between Régine Chopinot (who was Alain Buffard¹s choreographer when he was still a dancer) and Alain Buffard (now a choreographer) in Wall dancin’… First, Régine asks Alain to execute a certain number of poses which he does, a little “off,” eventually coming up with the “correct” movement. Then it is Alain’s turn to order Régine to perform impossible, nearly sadistic phrases and she submits to it but must inevitably fail. Or and this is much nastier, Laurence Louppe learns German by repeating the story of Heidi, a perfect little girl who wants to please the world and who is therefore extremely submissive. During this time she is literally manipulated by one of the others, forcing her to dirty herself by thrusting her forearms into a basin filled with tomatoes,

or forcing her to perform crazy gestures. It is a way to twist that famous line by Spinoza, “One does not know what the body can do or what one may deduce when considering its nature.” 2. Or perhaps to give it its true value, going against

the interpretations currently in fashion, whose terrible, striking echo is reflected in the final phrase of Les Inconsolés: “you learn it.”

Derision

The element of (auto)derision is almost never absent from the works of Alain Buffard. It can even become sort of sit-com, somewhat sketchy, as at the end of Good Boy or confirmed, as in (Not) a Love song, Self & Others or the lecture in Dispositif 3.1. For him, laughter is a subversive weapon. In most of his works there is usually a comic element

— which is also a trap. It consists of saying what the work is doing, thus cancelling it out. It¹s a turnaround which cleverly explodes from the inside what we are in the middle of watching. A mechanism which is a kind of (auto)derision and there are lots of examples: In Dispositif 3.1, Laurence Louppe confirms in her lecture on contemporary art that a cardboard box “symbolises the critic of scenic space of Western performance based on the black box, with lines of convergence and perspective organising and reorganising the space where the bodies formatting it must appear.” Of course the

work is actually constructed to ruin that space thanks to its bi-frontal structure. Or still in the same work, “Heidi loves wigs,” which are practically a symbol of the piece. The same process happens in Wall dancin’ Wall fuckin’: during a song in

English which is only about touching and seeing (a repeating element in the piece) where we hear, “I don¹t know where you’ve been/ I am watching you on the screen,” another way of highlighting something while annihilating it at the same time. Then there is (Not) a Love song. Although love and singing are central parts of this comedy which is in fact quite musical, punctuated by the song, “This is not a Love song” of course ends with the words, “I don¹t love you.”

1 And including some which are actually not his work.

2 in “L¹Ethique”

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: publicopt

Bailarino e coreógrafo francês Alain Buffard, um artista cuja obra, muito influenciada pela dança experimental da norte-americana Anna Halprin, era ao mesmo tempo íntima e política.

“Grande poeta do palco, bailarino, coreógrafo, encenador, Alain Buffard nunca deixou de questionar o nosso olhar sobre o humano”, disse a ministra francesa da Cultura, Aurélie Filippetti, que ontem lhe prestou homenagem, elogiando o seu trabalho de “artista comprometido e defensor incansável das liberdades”. As obras de Buffard, acrescentou a ministra, “são frágeis e fortes, violentas e delicadas, e sempre portadoras de sentido”.

A programadora Cristina Grande, responsável do serviço de artes performativas da Fundação de Serralves, onde o bailarino e coreógrafo actuou mais do que uma vez, lembra-o como “um homem muito especial”, um artista “muito lúcido e muito crítico, com uma obra de dimensão política muito forte”, mas também alguém “muito generoso e que gostava de partilhar”.

Buffard esteve pela primeira vez em Serralves em 2003 para apresentar, no âmbito do programa paralelo da exposição Caged-Uncaged, de Francis Bacon, a peça Good Boy (1998), um trabalho no qual reflecte sobre a SIDA e a influência da doença na dança. Good Boy, uma peça que reflecte também o seu encontro com Anna Halprin, tornar-se-á uma obra central na sua carreira, tendo regressado a ela várias vezes para criar novas coreogreafias, como Good For… (2001) ou Mauvais Genre (2003), um dos seus trabalhos em que colaborou a coreógrafa e bailarina portuguesa Vera Mantero.

Em 2009, Buffard esteve novamente em Serralves, no Porto, por ocasião da apresentação de Parades & Changes, a reencenação de Anne Collod da pioneira peça que Anna Halprin criou nos anos 60 e que foi banida nos EUA. Além de ter dançado, Buffard apresentou também, na mesma ocasião, o seu filme Lunch With Anna, de 2004, testemunho do seu encontro com a coreógrafa Anna Halprin.

Alain Buffard, que trabalhava desde 2010 com o Théâtre de Nîmes, como artista associado, nasceu em Morez, no leste de França, em 1960, e iniciou-se na dança em 1978, como aluno do coreógrafo americano Alwin Nikolais no Centre Nationale de Danse Contemporaine de Angers. Nos anos 80 trabalhou com coreógrafos como Brigitte Farges, Daniel Larrieu, Régine Chopinot ou Philippe Decouflé, tendo assinado a sua primeira coreografia, Bleu Nuit, em 1988.

Trabalhou depois numa galeria de arte contemporânea, e também como crítico de arte, antes de regressar à criação coreográfica no final dos anos 90, com Good Boy. A sua obra mais recente é Baron Samedi (2012), uma peça que associa a figura homónima da tradição voodoo ao universo musical de Kurt Weil.