DAVID ROKEBY

大卫·罗克比

데이빗 로커비

Hand-held

source: davidrokeby

David Rokeby is an installation artist based in Toronto, Canada. He has been creating and exhibiting since 1982. For the first part of his career he focussed on interactive pieces that directly engage the human body, or that involve artificial perception systems. In the last decade, his practice has expanded to included video, kinetic and static sculpture. Awards include the first BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) award for Interactive Art in 2000, a 2002 Governor General’s award in Visual and Media Arts and the Prix Ars Electronica Golden Nica for Interactive Art 2002. He was awarded the first Petro-Canada Award for Media Arts in 1988, the Prix Ars Electronica Award of Distinction for Interactive Art (Austria) in 1991 and 1997. See the “Invent” issue of Horizon Zero featuring a variety of perspectives on David’s work.

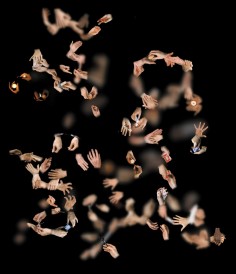

Hand-held is an installation that consists of an apparently empty space which reveals its contents as you explore it with your hands. Today, we regularly use our hands to navigate virtual commercial, social, political and information spaces and relationships using touch-screens, mice and keyboards. Hands, which have evolved to have a great degree of articulation and high concentrations of nerve endings, are reduced to pointers and signifiers.

The work occupies the exhibition space in the manner of a sculpture but is initially invisible. Your hands are your active agents with which to explore the space. When your hand moves into the space occupied by a part of the sculpture, its image appears on the skin of your hands and fingers as though it were physically present there. Moving your hand around allows you to discover the extent of the object and its relationships with things around it. As you approach an object, it is first blurry, then comes into focus as your hand comes closer. As your hand passes beyond it, the object against loses focus and dissolves. Some things move as you pass through them as though a short sequence of video frames is spread through space. In other cases, you see a fluid series of cross-sections of the interior of the object as you pass through it.

The invisible sculpture is built largely of hands and of objects we hold. The hands (cut off from their bodies like those of the tormenters in Fra Angelico’s fresco of the Mocking of Christ) touch each other, pass objects between them in social, practical, financial and symbolic gestures. It is a sort of network of engagements and transactions haunted by spectres of tactility and intimacy.

At the same time it is an evocation of the fullness of the apparently empty space all around us… occupied by our projected ideas, our voyeuristic and surveillant gazes, emotional charges, and, ever more so, the invisible communications through which we increasingly convey information, conduct transactions and relate to each other. The installation occupies a 3 meter by 3 meter area. Two HD projectors and a kinect depth sensor are suspended above. The projectors project images only where they see the body of the visitor. The space is filled with 80 layers of image, each approximately 1 cm thick. The image received on one’s hand is of the image layer present at your hand’s height in space. Layers seamlessly dissolve into each other, and particular hands and objects fall in and out of focus as you approach and move away from their core position in space creating a strong sense of depth in space and at the same time producing a sense of ephemerality and flux. On the other hand, the slight warmth of the projection where images of hands are present adds a haunting sense of presence and tactile immediacy.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: laboralcentrodearte

David Rokeby studied at the Ontario College of Art. Using technology to reflect on human issues, he has won acclaim in both artistic and technical fields for his new media artworks. A pioneer in interactive art and an acknowledged innovator in interactive technologies, he has seen the technologies which he develops for his work given unique applications by a broad range of arts practitioners and medical scientists.

Rokeby’s best known work, Very Nervous System (1986-90) premiered at the Venice Biennale in 1996, won the first Petro-Canada Award for Media Arts in 1988, and is permanently installed in several museums around the world. The work uses video cameras, computers, and synthesizers to create an interactive space in which body movements are translated into music.

The technology Rokeby developed for this work is widely used by composers, choreographers, musicians, and artists. It is also used in music therapy applications and is currently being tested as an activity enabler for victims of Parkinson’s Disease. Other works engage in a critical examination of the differences between human and artificial intelligence.

The Giver of Names (1991-present) and ncha( n)t (2001) are artificial subjective entities, provoked by objects or spoken words in their immediate environment to formulate sentences and speak them aloud. Rokeby has twice been honoured with Prix Ars Electronica of Distinction (Linz, 1991 and 1997). He has been an invited speaker at events around the world, and has published two papers that are required reading in the new media arts faculties of many universities. He recently received a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: laboralcentrodearte

Located at the entrance of the Galería de Exposiciones [Exhibition Gallery and Hall], the piece’s apparent innocence does not make it possible for us to really know how it works until the spectator is positioned on it and interacts. The space of the work is activated by human presence, generating a projection of hand images onto the body which multiply and perform different actions.

What we find interesting is playing with our own hands to see other ones which are superimposed, converting our bodies into a part of the piece. Also, at a certain height the images change, transform, and we have to move to be able to make out all of them.

This conjunction of technology and human intervention is very interesting and is the central theme of the entire exhibition which, as its name indicates, attempts to reflect on how technical and technological evolution condition our way of seeing the world, of how we interpret and experience it, and this is something that plastic arts also work with.

The body has been the object of artistic representation over the course of the history of art, but it wasn´t until the beginning of the 20th century that it also became the subject through different performances, many originating from the theatre.

At the time when digital media began to develop in art, especially in recent decades, it was predictable that this conjunction of technology and the body was given since scientific research in both fields has gone hand in hand for many years. Isn’t technology ultimately a means of improving our place in the world? Isn’t it aimed at facilitating our existence in the space we occupy?

The work by Rokeby holds a part of all of this; it is about being changed into the subject and object: as an active agent that is located in a determined space that interacts with the piece, and as an object of the work, with the hands as the proposed theme which additionally move and change depending on height.

Benjamin Weil, Artistic Director of LABoral and Curator of Elastic Reality, said that this concept “is a state of reality combining all of these layers which describe the complexity and instability of the real”.

Reality, therefore, has become changeable, flexible… And art has been transformed with it. The information has been converted into an artistic piece. The conceptual, as reiterated by Kosuth’s Chairs, have won the battle, and the intangible seems to be the new protagonist of the reality. From smart phones to the internet, the constant flow of information continuously reaches us and, at times, even overwhelms us. It is necessary, therefore, to stop and try to find a proper sense of this new reality.

And this, in the end, is what art has always been about: seeking to be the medium that explains what we are doing in the world and how we interpret it according to the historic time.

We could say that we are living through an elastic historic moment and that this exhibition shows the complexity of this instant through its different pieces.

The sub-heading of Beyond the Exhibition: new interfaces for contemporary art in Europe reflects this idea once again – not only the progressive dematerialisation of art work but also the actual disappearance of the idea of exhibition in its more classical form. The exhibition is no longer a determined physical space but an idea, and as such may be placed anywhere (as an example of an innovative project we could mention La exposición expandida [the Expanded Exhibition], that turned blogs into spaces for exhibiting.

In additional entries in this blog other works have been analysed, such as the one by Maya Da-Rin, who again reminds us of the current reality, that of constant surveillance through mobile devices.

Elastic Reality is a complete exhibition, a labyrinth to be entered so as to find different interpretations of the present time through very accomplished pieces.

In my case, I have deliberately chosen the work by Rokeby for all of its metaphorical and imaginary content. The simple projection of some hands in different attitudes reflects a whole series of concepts as interesting as intervention, reality, corporality and action, among others.

Without a doubt, it is a piece to be enjoyed live, playing with our hands and those of the anonymous protagonists from the projection.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: culturaelpais

Cuando llegaron los adjetivos, la realidad perdió su función para convertirse en virtual, socialista o paralela. Fiscal, aumentada y hasta telerrealidad. Cabría definir la suma de todas ellas como Realidad elástica, concepto que sirve a Benjamin Weil, director de actividades del centro de arte gijonés LABoral, para agrupar como comisario en una exposición inaugurada este fin de semana una decena de obras de jóvenes creadores que hablan de “nuevas interfaces para el arte contemporáneo en Europa”.

Como punto de partida puede sonar abstruso, pero la teoría de Weil debería resultar tan familiar a estas alturas como un teléfono inteligente, un rato muerto en Facebook o uno de esos rituales sociales que solíamos llamar comida y que ahora resulta constantemente interrumpido por los whatsapps recibidos por sus participantes. De la suma de todas las capas de la experiencia, de todos los niveles de interacción, de todos los flujos de información que componen nuestras vidas desde la irrupción de Internet, surge el concepto de Weil, sustanciado en la muestra en las obras escogidas entre los 48 proyectos desarrollados en 2012 por los becarios (y mentores) de la prestigiosa escuela francesa Le Fresnoy Studio National del Arts Contemporains.

Entre ellos, Weil ha destacado una decena de trabajos. “Fue un proceso distinto al habitual en un comisario. Más que elegir obra para sustentar una teoría, tuve que hallar un marco conceptual para englobar a las piezas existentes”, argumentó el sábado ante la obra que abre la exposición: un trozo de moqueta negra. En la penumbra de la sala parece un agujero cuadrado, un trampantojo de los de toda la vida. Cuando uno se sitúa encima de ella, se descubre el truco: la proyección de una selva de manos entrelazadas se anima al reflejarse sobre la piel del visitante en una metáfora que evoca los distintos planos del contacto carnal en esta era poshumana.

La misma sensación de juego revelador propuesta por David Rokeby sobrevuela el resto de las instalaciones. En una de ellas, firmada por Pierre-Yves Boisramé, la maqueta de un teleférico se mueve sin moverse del sitio merced a una escenografía escultórica de tintes cinematográficos. En otra, de Véronique Beland, las señales recogidas por un telescopio interestelar situado en Onsala (Suecia) se traducen en frases inconexas tableteadas en papel continuo por una vieja impresora. Y si en Horizonte de sucesos #Camuflaje, Maya Da-Rin burla moviéndose en círculos el control de un GPS en el Jardín Botánico de Gijón, Tutti, de Zahra Poonawala, construye una orquesta con altavoces que reaccionan a la proximidad humana.

Tras el recorrido prevalece la idea de que con este mismo conjunto de obras se podrían haber armado muchos discursos, pero pocos con la efectividad del propuesto por Weil, tan preocupado desde su posición en la LABoral por “la presentación al público del proceso creativo más allá del producto artístico”, como por crear vínculos entre la tecnología y el arte y entre las empresas de I+D y la cantera creativa europea.

Incluso aunque a diario se dé de bruces con otra realidad: la presupuestaria. El centro, que maneja 1,2 millones de euros, de los cuales la mayor parte se va en mantener la realidad paralela de la vieja universidad franquista que lo alberga, ha visto reducida a la mitad su asignación desde 2011.