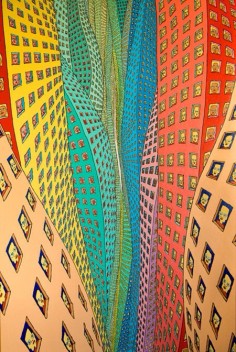

Hariton Pushwagner

Vertigo 23

source: artdiscover

Hariton Pushwagner es el pseudónimo artístico de Terje Brofos.

Él fue bautizado Terje Brofoss y nació en Oslo en 1940. Su nombre de su artista es un genuino invento de la era hippie. Hariton viene de “Hari ” como en “Hari Krishna” – el “ton” se añadió sólo por darle algo de peso. “Pushwagner “es una alegoría peculiar a la sociedad consumista y los carritos de compra en los supermercados.

Durante los últimos 20 años su obra principal “Un día en la vida de la familia Mann” ha perseguido a Brofoss como un niño indefenso.

En 1980, intentó liberarse del alcance de su obra con una exposición en el Centro de arte de Hovikodden, pero el interés del público fue más bien pobre.

En 1988, formó parte del Hotel Chelsea en Nueva York, donde se creó la versión final de la obra. La serie despertó la atención en los círculos de arte americano.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: theguardian

Reading this on mobile? Click here for the video

Pushwagner’s magnum opus, the graphic novel Soft City, is as feverish as a nightmare acid trip. Across 154 now-yellowing original sheets, in thin pen lines, a numbed world unfolds in relentlessly repetitive detail. It pictures identical family units en masse, going about identical lives, in apparently infinite identical flats and offices, in tower blocks that stretch upwards and outwards forever.

The story is simple and circular: get up, take a pill, kiss the baby, go to work, punch in, punch out, go home, kiss the baby, go to sleep. Everyone frogmarches to the same rhythm, ruled by the clock (if you’re late, you’re fired). Everyone drives – the multistorey car park is a major fixture. Everyone’s happy: for Soft City inhabitants, the mind is as much a prison as the routine lifestyle and oppressive architecture. There is no sky; there is no way out.

Soft City was created in the 1970s, fuelled by a dystopian vision the artist shared with his friend and mentor, the counter-culture novelist Axel Jensen, whose celebrated science fiction books he illustrated. The graphic novel then disappeared for decades, in which Pushwagner’s life went on a downward spiral from making art to marital breakdown, heavy drug use and, in the late 1990s, two years sleeping rough.

In his native Norway, the septuagenarian is now a celebrated square peg, as notorious for his wild lifestyle as he is for his unforgiving comic art. Literally “picked up from the gutter” by his manager, Stefan Stray, he’s only been more widely appreciated in the last decade. The recently rediscovered Soft City was one of the standout works in the 2008 Berlin Biennale, while a Norwegian documentary released last year chronicled his topsy-turvy life.

All of Pushwagner’s work builds on Soft City’s core themes, which are rooted in classic dystopian sci-fi. Think of the mechanised underworld of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, or the social classes polarised by Blade Runner’s soaring skyscrapers. His 1990 painting series Apocalypse Frieze focused on military factories churning out war machines and carnage. A Day in the Life of Family Man, a wickedly funny set of pink, grey and black silk screenprints conceived with Jensen in 1980, brings billboard advertising, surveillance technology and TV-as-placebo into the picture.

Indeed, with the recent rapid rise of power with a friendly face – from Ikea villages to self-policing social media – his vision feels more and more prophetic.

Why we like him: For the fiendish work Jobkill, the central painting in Apocalypse Frieze. Revellers dine and dance on the decks of an armoured battleship, sailing on a sea of bones. The landscape is black with tanks, police vans and fighter planes, and parachuting soldiers fill the sky.

Name game: Hariton Pushwagner is a moniker that the artist, born Terje Brofos, adopted in 1970. It’s a nod to Hare Krisna and Eastern philosophy, and push wagons or shopping trolleys.