KAO CHUNG-LI

source: taipeibiennial2012org

Kao Chung-Li’s work investigates the relationship between history and personal biography, between time, images, and media. He is a photographer and a collector of historical pictures as much as a filmmaker, animator, and media-archeologist. “Taking a picture means an interruption of reality. Showing that picture means a cessation of fantasy,” states the artist. For him, the slideshow in particular sustains a tension between image, time, and stillness—and is situated beyond fantasy and reality, subsuming both photography’s indexical relation to past events, and the expectancy of cinematic time and storytelling.

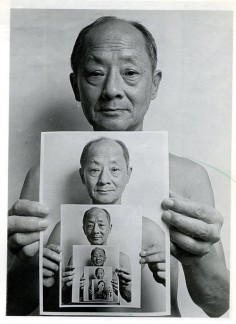

The protagonist of both works—a slideshow and a new video—shown here is Kao Chung-Li’s father, now 93 years old. The story told spans more than 90 years. A key motif in this work is the bullet in the father’s body, which has remained in his lower cranium since the days of the Chinese Civil War. Shot in the head by the Liberation Army during the Huaihai Campaign in 1948–49—a battle that was decisive for the victory of Communists over the KMT—this bullet has remained as a material witness.

Chung-Li’s father was born in the year of the May 4th Movement, and thus his biography stands for the Chinese historical experience of the twentieth century, set against the global histories of colonization, the wars of decolonization, and the struggles against neo-colonialism in the era that has called itself “globalization.” What is being told here is a counter-story to the hegemonic version of a “universal history” entailed in the propagandistic promise of progress and modernization. The universality of historical experience —that is, general validity beyond a particular context—is here equated with the systemic violence suffered by the vast majority of humanity under colonial and imperialistic regimes. “History is like a language; it is not merely some random noises. A lot of histories are like dialects—restricted by region. Some histories, however, cannot be so restricted,” states the artist in commenting on the work. “If we compare my fathers age to a language, I think we ought to learn that language, at least enough to comprehend it.”

The new video The Way Station Trilogy completes the biography, interlacing the father’s recollection with animated scenes, childhood memories, and Kao Chung-Li’s own life.

Kao Chung-Li, born 1958 in Taiwan, lives and works in Taipei

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: atfmasia

Kao Chung-Li’s artistic career is unique in comparison to most Taiwanese artists. Crossing over filmmaking (experimental, animation and documentary films) and visual art practices such as painting, sculpture, photography and installation. In the eighties, on the one hand, he won several Golden Harvest Awards in the field of filmmaking (in Taiwan) and, on the other hand, took part in the artists group ’Living Clay’ that already put out experimental projects in non-official and unconventional venues when the country was still under the martial laws. The group carried out a series of projects until the end of the nineties, following a consistent anti-establishment conceptual line ; other artists taking part included Lin Ju and Chen Chieh-Jen.

The hand-held projector modified by Kao Chung-Li is constituted of an old cassette as its structure. The viewer sees 8mm film by operating the handle. Courtesy–Tina Keng Gallery, EX!T Experimental Media Art Festival in Taiwan. Copyright–Kao Chung-Li

The diverse artistic attempts of Kao Chung-Li actually center on experiments around the ‘motions of images’, with the 8mm film as his primary medium along with various audiovisual machineries that he reconstructs. Some of the pieces belong to the ‘Photochemical Mechanical Mobile Images’ series which he started in 1998. According to the artist, ‘[…]I continue to make the ‘‘Photochemical Mechanical Mobile Images’’ installation series. Being displayed, they also simultaneously reveal themselves on a minimal degree, which signifies an existence that runs towards the irretrievable and the destruction of the image. The shooting, the hand-drawn animation and projection principles are all visualized in the best possible way through the form of installations. It is an attempt at simultaneously activating several dimensions : those of philosophical, of poetry, of politics, of economy, of history, of aesthetics and of technology. Such is an apprehension that refuses to be inverted.’

Till today, at a time when digital technologies progress and pervade, Kao Chung-Li remains attached to the materials and technologies of image-making that are regarded as outdated, some even simply disappeared ; just as he consistently explores visual machines as an incarnation of power operation and conceives possible ways to its destruction through studying and writing on the history and theories of the image, experiments about various forms of making, treating and showing images, as well as direct intervention on the material level of the visual machine. And if we transpose the metaphor of the act of viewing as incarnation of power relations into the particular context of Taiwan, such visual experiments by Kao Chung-Li actually constitute a resistance to the audiovisual equipment and products largely poured in by the First World (primarily the U.S.). As he states, it is an attempt to ‘push to its end the task of liberating The Third Visual World—the world of the audiovisually disadvantaged.’

Such approaches, concepts and concerns about institutional issues residing in Kao Chung-Li’s oeuvre are epitomized in his recent solo exhibition in Taipei featuring a film, a slideshow with soundtrack and a few projection machines re-composed by the artist. The film ‘My Mentor, Chen Yingzhen’ (2010) is about one of the most important writers in post-war Taiwan who represents an intellectual that insists on his leftist position in an era of political tension. Kao Chung-Li has been part of the study group presidedby Chen Yingzhen ; their mentor-discipline relationship and also friendship were captured in the home movies shot by the artist. Flashbacks of the writer in the middle of meetings or outings with friends and family became a major part of ‘My Mentor, Chen Yingzhen’.The film is also interspersed with archive sequences about Chen Yingzhen : in demonstrations, lectures, etc. along with illustrations by the artist that were based on Chen’s figure and his life story. Such an indirect, somewhat discontinuous potraiture/documentary also contains disjointed sequences or other kinds of ‘disordered’ images, thus intervening in the narrative as well as reminding the viewer of the image’s particular characteristics (which no longer represents itself as a smooth illusionary representation in which one is immersed) so that he/she becomes aware of his/her own viewing act. All these features echo the theme of the curator Liu Yong-Hao’s curatorial statement : ‘Repeat and Pause’.

Another particularity of ‘My Mentor, Chen Yingzhen’ (a work that can be considered one of mixed-medium, including diverse visual materials such as animation, shot sequences and archive footage) is that it also features documentary sequences of the projection process of ’paper-play slides’ fabricated by the artist, thus evoking memories of these images being displayed upon meetings with Chen and considering the projection act as a kind of ‘performance’ that one would ‘exhibit’ and ‘document’. As for the format of the work, although the work’s final version is digital, yet it was also digitalized in a ‘handcraft’ fashion, a method that the artist always employs. Precisely, the transfer was achieved through filming (in digital) images projected from footage or slides without eliminating the noise of the projector. On the one hand, the feeling of ‘live practice’incarnates the artist’s idea of visualization (as aforementioned) : making visible the process of generating images as well as related machineries; for example, the often dismantled audiovisual machineries are shown in the way one would show an exhibit (with lighting for a sculpture work, for example). Therefore, the power of viewing is transferred to the viewer (who can now see through the machine) and the machine which is assigned with the task of fabricating images/illusions is transformed into an object of gaze or a kind of kinetic sculpture. On the other hand, it also constitutes the work’s heterogeneity in spite of its final digital format. As the artist puts it, ‘With the site of performance where the functions of projection and that of taking pictures are displayed all together, the action, the object and the result of image transfer at the moment of projection and of viewing – even though they are meant to be captured by the collective visual unconsciousness constituted of the histories of pre-cinema, of cinema and imagery and thus have no choice but to be assimilated as new objects of aesthetics – still preserve their heterogeneity.’

Besides, the ‘slideshow briefing cinema’ (according to the artist) featured in this show : ‘The Taste of Human Flesh’ (2010) also reflects the History through personal stories. This time, the protagonist is the artist’s father who took part in the battles between the Communists and the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, KMT). He was shot by his neck and the bullet still stays inside his flesh. The voice-over (recited by the artist) is played from a cassette, recounting from the bullet’s first-person point of view (’I am a bullet’) about the young body where it rests as well as countless other bodies of the anonymous individuals under wars. The visual aspect of the work also combines mixed materials such as photographs of as his father, archive footage, virtual images, shot sequences as well as images showing paintings appropriated from the art history, thus extensively referring to thoughts upon war and colonization in relation to all humankind ; such a long process that evolves alternatively and successively in the West as well as in the East has now taken on the name of ‘globalization’. The voice-over goes on to evoke two contemporary historical events : the inauguration of Hollywood film industry in the U.S. and the Revolution of 1911 in China (the Chinese bourgeois democratic revolution led by Dr. Sun Yat-sen which overthrew the Qing Dynasty), thus reiterating the thesis of ‘image as hegemony’. As for the audiovisual construction of the work, again, it reveals itself as a heterogeneous and ambiguous intricacy : the static slide images, the (semi-)continuity interspersed with perceptible breaks along with the autonomous soundtrack from the cassette are nothing but another hybridization act towards the motion of cinema ( visual illusion made with successively displayed individual frames of static images ) and the attached-yet-detached relation between the sound and the image, as the artist puts it, ‘being played, the procession of cassettes and slides preserves their respective autonomy regarding the sense of time and the sense of space and, through their mutual infiltration, further develops a continuous audiovisual relation that is sometimes detached, sometimes attached.’

Through the two pieces as well as a few recomposed vision machines on show, the show incarnates the ultimate attempt of Kao Chung-Li’s practices about images : to change our ways of seeing and of perceiving history and social reality. The condensed form of the show is proposed by Liu Yung-Hao, the curator, in the frame of ‘2011EX!T Experimental Media Arts Festival in Taiwan’. Not only does it stands as an example in contrast to groups shows or film festivals with abundant films, but its venue – inside an art gallery(Tina Keng Gallery, date : 2011.11.18-11.27)– is unusual for a generally termed ‘experimental film festival’ in a strict sense. The project thus corresponds perfectly to Kao Chung-Li’s own line : bordering on experimental cinema and contemporary art, and tests the limit between generally termed experimental cinema and art. Above all, it offers a positive reply to link the two fields whose distinction is more than often questioned upon.