LINDER STERLING

source: colunaesplanada

Nascida em Liverpool no ano de 1954, Linder Sterling (nascida como Linda Mulvey e que assina apenas Linder) é, além de artista plástica, performer e música. Hoje, após ter morado durante dez anos em Manchester, onde estudou na conceituada faculdade de artes Manchester Polytechnic, mora em Lancashire.

Como uma feminista radical e hiper conhecida na cena punk and pós-punk, Linder acertou em cheio o mote desta exposição: “Linder, Femme/Objet” que, como um “slogan”, trás o princípio gerador do trabalho e ainda como a artista britânica orienta o conjunto de sua obra onde abusa da foto-montagem, da performance e do vídeo para denunciar o machismo.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: 032c

Born in Liverpool, LINDER STERLING studied art and design at Manchester Polytechnic in the late 1970s. She was in the year above the graphic designers Peter Saville and Malcolm Garrett, and in 1977 Garrett used a photomontage she had made for the cover of Buzzcocks single “Orgasm Addict,” a piece that has since become one of punk’s iconic images. In 1978 Linder formed the band Ludus, joined in 1980 by Ian Devine. At a performance at Manchester’s Hacienda she wore a dress made of meat with a dildo as a means of satirizing the club’s policy of showing pornography as entertainment. The evening remains a seminal moment in the history of sub-cultural Manchester. Ludus were signed to the Manchester label New Hormones and also the Belgian label Les Disques du Crepuscule in 1982, but disbanded disharmoniously soon after.

Possibly most famous for being Morrissey’s best friend, Linder is also celebrated for her uncompromising feminist collages and more recently her installations and performances, many of which take place in a psychic territory she calls Linderland. She took part in the 2006 Tate Triennial with a performance that pitted three Northern rock groups against a dozen women performing Shaker rituals.This work is part of a dual fascination with a model of masculinity epitomized by Clint Eastwood’s appearance in the films of Sergio Leone, and a form of quiet female resistance represented by the founder of the Shaker movement, Ann Lee.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: theguardian

“One name seemed sufficient.” Since the late 1970s, the English artist Linder has sculpted – or more accurately, in light of her signature photomontages, scalpelled into being – a persona and a body of work that are discreet as well as scandalous, earthy and visionary. At the heart of her work is a vexed idea of glamour, in its older sense of a sinister lure or spell – Linder’s art has long been obsessed with both the exploitations or liberating potential in contemporary media and style, and with certain ancient ritual scenes and personae culled from an occult or outsider culture. She is as likely nowadays to use images from pornography or advertising as she is to appear in person tricked up as a witch or medium, channelling energies from the material present or a deep spiritual past.

Born Linda Mulvey in Liverpool in 1954, she became (or invented) Linder in Manchester in the mid-to-late 1970s, assuming punk’s “transformative plumage” – already an art-glam casualty thanks to Roxy Music, she was known to stalk the streets in Waaf uniform and red stilettos. She played a key role in the city’s aesthetic and political response to the galvanising arrival of the Sex Pistols in June 1976. To this day she remains best known for the posters and record sleeves she made for her equally punk-energised friends, Buzzcocks, the following year. But Linder, with her single and singular name and her unsettled sense of what “Linderland” (a later imagined rubric in which to corral her disparate activities) might contain, has been many artists: photomonteur indebted to Modernism, musical conduit from 1970s feminism to art-inflected post-punk, collaborator and adviser, too often dismissed as “muse”, for others such as Morrissey and Magazine vocalist Howard Devoto, latterly contriver and often star of shamanic and gruelling gallery performances.

In the past decade, so much of Linder’s early art – including the well-known Buzzcocks collages that had been languishing in under-the-bed boxes for years – has been the subject of numerous gallery shows. The early work is installed permanently at Tate Britain and was lavishly reproduced for a 2006 catalogue. It has also ghosted a good deal of her later photomontage and performance. For all her mercurial shifts of medium, genre and self-definition, Linder’s career has been remarkably of a piece. An exhibition earlier this year at Stuart Shave/Modern Art in London (a substantial retrospective show is to follow at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in the autumn, and she is currently in an Arts Council England touring show of collagists), revealed an artist bringing her imagery luridly up to date while maintaining an unmistakable style and texture.

Here were large-scale photographs (displayed for the first time in lightboxes) of her latest montages: originally hand-spliced (then rephotographed) juxtapositions of images from contemporary porn magazines, pictures of cars, cosmetics and accessories from more mainstream magazines and queasily close-up photographs of food. The bodies, objects and surfaces were recognisably 21st century, but details and composition seemed oddly out of time, not least because the imagery was excised from print magazines and not from the internet, but also because the completed works so readily recalled Linder’s first photomontage experiments. Her pairings of different types of consumerist desire, which once declared themselves as critiques of misogynist objectification, are now equally a part of an abiding artistic practice. For example, looking at a particular conjunction of mock-ecstatic porn performers and ornate confectionery, we get the “message” but know too that we can only be in the obsessive, repetitive world of Linderland.

Some of Linder’s recent work explicitly recalls the visual environment in which she first took up her scalpel and a stack of magazines. One series brings together photographs from 1970s men’s magazines, with their suggestions of framing narrative around the central act of revelation or performance, their distractingly busy decor and (so it seems in comparison with the contemporary images) unnecessary props and other complexities in the background. Photographs are less sharp, colours muddier, models less airbrushed. (The temptation is to say also less alienated, though this is no doubt a lure of such vintage imagery in general.) Considerably more alarming was a series of photographs of Linder and an American gallerist accomplice covered in a wild array of gloopy, dripping colour; in one image, only the artist’s eyes were recognisable, such was the quantity of what seemed to be viscid pigment. It turned out to be a selection of various foodstuffs – custard, rice pudding, raspberry sauce – and the photographs an antic reference to, as Linder puts it, a very English type of pornography. “Splosh” fetishists are typically somewhat sadder creatures than these – the whole thing smacks abjectly of the nursery – but Linder and friend looked like glamorous aliens or a kind of deconstructed Leigh Bowery.

By the late 1970s, Linder was already considering her photomontages as creatures of a sort; she has spoken of the process of cutting and splicing as, “performing cultural post-mortems and then reassembling the corpses badly, like a Mary Shelley trying to breathe life into the monster”. Equipped with a sheet of glass, glue and a Swann-Morton No 11 scalpel, she emerged from Manchester Polytechnic, where she studied graphic design, calling herself a “monteur” and with certain key artistic influences in place. The political works of John Heartfield and George Grosz were crucial, though in its ambiguous critique of modern glamour her early art was also indebted to the prewar montages of Hannah Höch, with their alluringly odd redeployment of magazine images. As an adolescent in a house with few books, Linder had been politicised by Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch, and by the mid 1970s Spare Rib was her “Bible”. Avant-garde aesthetics and feminist politics now combined to produce an art of fearless effrontery.

Her cover for Buzzcocks’ Orgasm Addict is merely the most notorious image of this period: a naked woman’s body brutally topped with a Morphy Richards iron where her head should be and grinning lipsticked mouths for nipples, neatly complementing the song’s tale of mechanically compulsive sex. (Subsequent exhibitions have revealed that the black-and-white sleeve image was originally in lurid colour, the faceless body oiled and glistening.) In a stark and amusing appraisal of the conventions of top-shelf misogyny, Linder’s early montages depict soft-porn scenes invaded by the shiny tat of domestic technology – Super 8 cameras for heads, vacuum cleaners for genitals, a young woman in a photo-romance clinch stabbing herself in the eyes with a dinner fork. Some of these images were made for the Secret Public, the fanzine she contrived with the music critic Jon Savage, whose own more laconic montages look now like remnants of earlier pop art rendered bleakly up-to-date by the influence of JG Ballard and the Situationists.

In 1977, Linder formed a band, Ludus, with guitarist Arthur Kadmon, who was later replaced by her long-time (and current) collaborator Ian Devine. Ludus played a fretful and subsequently jazz-inflected post-punk, their singer’s playfully stentorian vocals (which Morrissey admired, and in part mimicked a few years later) describing vignettes charged with the sexual politics of the time and occasionally veering into ecstatic screeches. For all their daring, songs such as “Breaking the Rules” and “My Cherry Is in Sherry” were possessed of a pop sensibility that might have seen Ludus thrive in the ambiguous era of bands such as the Associates and (slightly later) the Smiths, but Linder’s persona was too restive. Among her last gestures before she and Devine split was an astonishing performance at the Hacienda in Manchester, on 5 November 1982. Video footage shows the vegetarian singer wearing a dress made of discarded chicken parts from a nearby restaurant and at the show’s climax ripping it off to reveal a shiny black strap-on dildo.

In some ways it is Linder the unruly performer who has returned in the past decade. As a physical presence in much of her recent work, she is no less formidable, nor any less conflictedly in thrall to the history and present potential of glamour, her own and others’. But she’s added to her intensively researched image repertoire an interest in visionary female predecessors such as the Manchester-born founder of the Shakers, Ann Lee and the subjects of early-modern witch trials. It’s this “hex factor'” as Linder puts it, that lends recent marathon gallery performances such as “The Darktown Cakewalk” and “Your Actions Are My Dreams” their dandy-occultist allure: Linder channelling mediums and beauty queens, ragtime performers and figures from magical English legend.

Montage, however, remains central to her art. The Arts Council’s collage show puts her in the presence of such disparate British artists as Richard Hamilton, John Stezaker and Grayson Perry, where her lacerating gaze seems more essential than ever.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: lespressesdureel

La carrière artistique de Linder Sterling (née Linda Mulvey à Liverpool en 1955, vit et travaille à Lancashire) s’étend sur plus de trente ans et couvre de nombreux champs culturels. Ses travaux ont eu un impact important sur le public à partir de leur diffusion au travers du fanzine punk The Secret Public, et de la pochette du premier single des Buzzcocks qu’elle a réalisée (Orgasm Addict). Linder a ensuite fondé son propre groupe Ludus avec Ian Devine et les amis qui posaient pour ses photomontages des années 1970.

Si ses apparitions publiques à l’époque sont restées célèbres dans le milieu musical (le mémorable costume de viande crue porté avec un vibromasseur noir à l’Hacienda…), c’est plus récemment que l’artiste a obtenu une réelle reconnaissance pour ses contributions visuelles à la scène punk et post-punk. Sans plan de carrière et en l’absence d’un réel soutien institutionnel jusqu’à récemment, son travail performatif et multidisciplinaire est à considérer comme partie intégrante de sa vie. Il a souvent été dit que Linder était le chaînon manquant entre Tracey Emin et Yoko Ono : la richesse visuelle de son travail et la singularité de sa démarche sont irréductibles à une filiation simple, aussi évocatrice soit-elle.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: denniscooper-theweaklingsblogspot

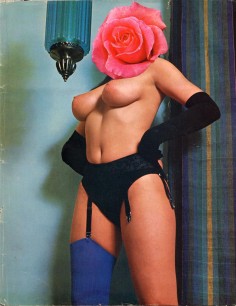

‘A radical feminist and a well-known figure of the Manchester punk and post-punk scene, Linder Sterling was known for her montages, which often combined images taken from pornographic magazines with images from women’s fashion and domestic magazines, particularly those of domestic appliances, making a point about the cultural expectations of women and the treatment of female body as a commodity. Many of her works were published in the punk collage fanzine Secret Public, which she co-founded with Jon Savage. One of her best-known pieces of visual art is the single cover for Orgasm Addict by Buzzcocks (1977), showing a naked woman with an iron for a head and grinning mouths instead of nipples.

‘”At this point, men’s magazines were either DIY, cars or porn. Women’s magazines were fashion or domestic stuff,” Linder has said. “So, guess the common denominator – the female body. I took the female form from both sets of magazines and made these peculiar jigsaws highlighting these various cultural monstrosities that I felt there were at the time.” Linder was also a partner of Howard Devoto, a founding member of Buzzcocks, who left the group to form Magazine. She also designed the cover for Magazine’s debut album Real Life (1978) and was known for her ‘menstrual jewellery’ (beads and ear-rings made of broken coat hangers with absorbent lint dipped in translucent glue and painted red, in order to resemble bloodied tampons) and the mythical ‘menstrual egg-timer’ (a series of beads with different colours – red, white and purple – devised to chronicle the cycle from ovulation to menstruation) that she designed for Tony Wilson’s Factory Records (designated Fac 8), which never entered production. She also collaborated on a short film called Red Dress, a rare Factory/New Hormones project.

‘In addition to visual art, Linder has in recent years devoted herself to performance art, which includes photography, film, print and artefact. Centred around the themes of outsiderdom, religious non-conformism, ecstatic states and female divinity/sainthood, her performance art evokes mythical figures ranging from historical figures such as St. Clare of Assisi and the founder of Shakers, Mother Ann Lee, to the Man With No Name, Clint Eastwood’s character from Sergio Leone westerns. “I find glorious parallels between Leone’s portrayal of the heroic and the malign with that of legal and illegal activity in north Manchester – or ‘Gunchester’. Think of it as Lowry with guns.”

‘In 1997 she put on a one-woman exhibition in London’s Cleveland Gallery titled What Did You Do in the Punk War Mummy?, and the next year she performed a work called Salt Shrine – filling a room in a disused Widnes school with 42 tonnes of industrial salt. In 2000, her work in different media was exhibited in Cornerhouse, Manchester, under the title The Return of Linderland, featuring the short film Light the Fuse, which combined re-enactment of scenes from Leone films – with Linder performing in drag as Clint Eastwood – with images of modern day cowboys and young men from north Manchester. Her performance pieces in subsequent years have included The Working Class Goes to Paradise (2001) and Requiem: Clint Eastwood, Clare Offreduccio and Me (2001). A new instalment of Working Class Goes To Paradise was played on 1 April 2006 in the Tate Gallery, as a part of the Tate Triennial 2006. With the musical accompaniment provided by three indie rock bands playing simultaneously for four hours, a group of women re-enacted the ritualisic gestures of 19th century Shaker worship, while Linder performed assuming different roles, including that of a figure from one of her photomontages, that of Ann Lee, and of a fusion of Ann Lee, Christ and Man With No Name. Audience members were able to view the performance and to join in.’ — collaged

‘In 1978, Linder Sterling co-founded the post-punk group Ludus, and she remained its singer until the group split in 1983. She designed many of the band’s covers and sleeves, or posed for artistic photographs taken by photographer Birrer and used for Ludus sleeves and the SheShe booklet that accompanied Ludus’ 1981 cassette Pickpocket. Ludus produced material ranging from experimental avantgarde jazz to melodic pop and cocktail jazz, characterised by Linder’s voice and unorthodox vocal techniques (which occasionally included screaming, crying, hysterical laughter and other unusual sounds), as well as her uncompromising lyrics, centred around themes of gender roles, love and sexuality, female desire, and cultural alienation. Although critically acclaimed, they never achieved any significant commercial success. Most of their material, originally released between 1980 and 1983 on the independent labels New Hormones, Sordide Sentimentale and Crepuscule, was reissued on CD in 2002 by LTM.’ — collaged

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: vietcuonghoangwordpress

Bảo tàng “Nghệ thuật đương đại” Paris, giới thiệu lần đầu tiên những tác phẩm của nữ nghệ sĩ Linder Sterling (gọi tắt là Linder) sinh năm 1954 tại Liverpool.

Với gần 200 tác phẩm được trưng bày, bao gồm nhiếp ảnh, tranh cắt dán, trang phục, những đoạn phim, âm thanh, những buổi “performance” (nghệ thuật trình diễn) mà cô đã thực hiện. Buổi triễn lãm giới thiệu ba trục chính trong tác phẩm của Linder: nghệ thuật thị giác, âm nhạc và thời trang.

Kể từ năm 1976, Linder làm việc với các loại hình nghệ thuật khác nhau, từ nghệ thuật thị giác đến âm nhạc thông qua một cái nhìn thời trang. Trong phần lớn các tác phẩm của mình, cô sử dụng phương pháp « ghép ảnh », đi theo phong cách của những nghệ sĩ theo trường phái Dada như John Heartfield và Hannah Hoch.

Đối với cô, những bức ảnh « cắt dán » tạo ra một cái nhìn mới, qua đó bày tỏ quan điểm về các hoạt động chính trị của nữ quyền. Linder giới thiệu tác phẩm của mình như là « auto-montage » (tự lắp ráp). Cô muốn phá vỡ hình ảnh về một người phụ nữ lý tưởng qua việc thực hiện những « bức chân dung của sự tha hóa » về chính bản thân mình.

Sử dụng những bức ảnh, những chi tiết trong những tạp chí khiêu, cắt dán, lồng ghép lên nó là những hình ảnh của tạp chí xe hơi, về văn hóa, về ẩm thực, mọi thời kì dường như lẫn lộn với nhau. Nữ nghệ sĩ muốn tố cáo những bạo lực vẫn đang diễn ra đối với người phụ nữ, khi mà người phụ nữ được xem như là một món hàng thương mại, hay chỉ như là một thứ “đồ chơi tình dục”.

Những tư thế chụp hình khiêu gợi mà chúng ta vẫn thường thấy trong các tạp chí khiêu dâm, Linder mở ra một cái nhìn về một xã hội tình dục phóng khoáng, phá tan những định kiến xã hội mà người đàn ông đã áp đặt lên người phụ nữ qua hàng thế kỉ.

Ngoài việc khẳng định về nữ quyền, Linder còn nhấn mạnh đến sự khiếm nhã mà chúng ta vẫn thường thấy trong hình ảnh quảng cáo ngày nay.

Linder còn hài hước đề cập đến Ballets Russes (một đoàn ba lê nổi tiếng tại Nga), cô tôn vinh các vũ công trong khi đó lại che khuôn mặt của họ vào bằng bánh, bằng các loại trái cây…

Trong buổi triễn lãm lần này, chúng ta có thể bắt gặp hình ảnh những người đàn ông đồng tính, bởi theo Linder “Tôi không thể tìm thấy sự khiêu dâm ở những chàng trai dị tính”.

Buổi triễn lãm “Femme/Objet” theo mình khá thú vị, nó là một tuyên ngôn, sự đấu tranh không ngừng nghỉ về nữ quyền, song qua cách thể hiện của Linder, triễn lãm trở nên đầy màu sắc, châm biếm và cũng đầy hài hước.

Nếu muốn có thêm thông tin về cuộc triễn lãm, các bạn có thể xem qua clip ngắn trong đó nghệ sĩ Linder giới thiệu những quan điểm của mình.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: kestnergesellschaftde

Als Linda Mulvey 1954 in Liverpool geboren, ändert sie ihren Vornamen als sie 22 Jahre alt ist, auch wegen des deutschen Klangs von »Linder«. Zu dieser Zeit studiert Linder in Manchester Grafikdesign. Die ehemalige Industriestadt ist Opfer einer schweren ökonomischen Krise, über 70% der Gebäude in der Stadt stehen leer. Über New York und London kommend stößt der Punk in das kulturelle Vakuum. Es beginnt mit einem legendären Konzert der Sex Pistols im Juni 1976, indessen Folge Bands wie Buzzcocks, Magazine, Joy Division, The Fall und The Smiths mit Morrissey Musikgeschichte schreiben. Linder ist eine Schlüsselfigur der Szene und schafft mit ihrer Collage für das Cover der Buzzcocks-Single »Orgasm Addict« eine Ikone des Punk: ein glänzender, nackter Frauenkörper mit zwei grinsenden Mündern auf den Brüsten und einem Bügeleisen als Kopf.

Linders Collagen folgen dem »Do-it-yourself-Prinzip« des Punk. In einem Spiel zwischen Offenbaren und Verbergen montiert sie Bilder aus Pornomagazinen mit Fotos von Haushaltsgegenständen, Maschinen, Kuchen oder Blumen – um nur einige der eingefügten Bildausschnitte zu nennen –, die meist den Kopf oder das Geschlecht verdecken. Seit ihren frühen Collagen aus den 1970er Jahren sind vorgegebene Bilder von Weiblichkeit, insbesondere der sexualisierte Körper als Konsumprodukt und die domestizierte Frau Hauptangriffspunkte von Linders Arbeiten. Dabei geht sie immer von vorhandenen Bildern aus, die sie durch Eingriffe mit dem Seziermesser in einen anderen Zusammenhang stellt, deren suggestive Kraft umleitet und ihre Bedeutung verschiebt. Dazu bemerkt Linder: »Collage hat auch ihre eigene Form der Gewalt, in der Bestimmtheit, mit der sie Bilder einfordert oder zurückfordert, die mit Punk übereinstimmt – mit schreiendem Gesang und zerschlagenen Gitarren […]. Mich interessiert die Bedeutung des Schnitts und was es heißt, heute auf die gleiche Art Collagen zu machen in unserer Gegenwart des ‚cut and paste‘, das ohne die physische Geste auskommt.«

Ein Spiel mit Geschlechternormen dokumentieren auch Linders Fotos von Transvestiten in Manchesters Dickens Club. Die Schwulenbar war ein Rückzugsort, wo man als Punk nicht wegen seines Kleidungsstils angefeindet wurde. »Die Männer und Frauen in dem Dickens Club waren alle geschickt darin, ein gespaltenes Leben zu leben, sie konnten mühelos darin wechseln als Mann oder Frau wahrgenommen zu werden – sie hatten die Sprachen von beiden gelernt und beherrschten beide fließend.« 1978 gründet Linder ihre Band Ludus. Im Begleitheft der Ludus-LP »Pickpocket« erscheint die Serie »She/She« (1981), in der sie auf kühlen Schwarz-Weiß-Fotos glamourös Gesten weiblicher Maskerade durchspielt. Zwei Jahre später wird Linders letzter Auftritt mit Ludus in dem Club The Haçienda, der sich einem unpolitischen Hedonismus verschriebenen hatte, zu einer provokanten Performance. Linder als überzeugte Vegetarierin trägt ein Kleid aus Geflügelresten, ihre Managerinnen verteilen im Publikum Fleischreste, die in Pornomagazine eingewickelt sind, der Club ist mit rot tropfenden Tampons dekoriert und schließlich offenbart Linder unter ihrem Kleid einen Dildo, den sie umgeschnallt hat. Sie singt und schreit: »Woman, wake up!«

Ebenso wie die Bilder, die Linder in neue Kontexte setzt, werden für sie auch Geschlechternormen zu flexiblen Rollen, deren Bedeutung in performativen Inszenierungen immer wieder verschoben werden kann. Die von dem Modefotografen Tim Walker fotografierte Serie »Oh Grateful Colours, Bright Looks« (2009) zeigt Linder aufreizend posierend als englische Hausfrau im durchsichtigen Kunststoffkleid mit Plastikkorsett. Linders Faszination für Tanz spiegelt sich nicht nur in Collagen mit Balletttänzern sondern auch in dem Kurzfilm »Forgetful Green« (2010), der innerhalb eines Tages nach der dreizehnstündigen Performance »The Darktown Cakewalk: Celebrated From The House of FAME« (2010) mit denselben Charakteren in einem Rosenfeld gedreht wird. Ihre Erschöpfung kehren die Beteiligten – darunter Linder als Minerva Maus – in eine unbekümmerte Leichtigkeit um und improvisieren eine Pastorale aus Verrücktheit, Begehren und Chaos.

Aggressive Hardcorepornos unserer Zeit verfremdet Linder, in dem sie diese mit Fotos von Kuchen verbindet. Von Food Designern gestylt und verführerisch in Szene gesetzt, bekommen die Kuchen im Zusammenhang mit den Pornos eine verstörend körperliche Qualität. Die Leuchtkästen annektieren Hochglanzbilder einer Werbewelt, in der Begehren allein auf konsumierbare Objekte gerichtet ist, alles dem Warenkonsum unterworfen und zum Objekt wird. Einer einfachen Unterteilung in die Kritik böser Pornografie und Vergegenständlichung vs. Konstruktion alternativer Bilder von Weiblichkeit entziehen sich Linders Arbeiten jedoch. Besonders neuere Arbeiten, in denen Linder Blütenköpfe auf heute fast antiquarisch anmutende Bilder von Pin-up-Girls montiert, wechseln mehrdeutig zwischen einer affirmativen Sinnlichkeit und der Überzeichnung gängiger Klischees von Weiblichkeit und Erotik. Linder stört den klar definierten Zweck der Bilder, und lenkt den Blick auf ihre bildnerischen Qualitäten auf unerwartete Analogien, Kontraste, und Spannungen. Sichtbar ist dabei immer auch die Lust, mit vorgefundenen Bildern zu experimentieren, sie mit fremden Bildern zu konfrontieren, ohne dass die Aussagekraft des Resultats immer vorhersehbar oder gar eindeutig bestimmbar wäre.