Liza Lou

ЛИЗА ЛУ

לייזה לו

汪明荃楼

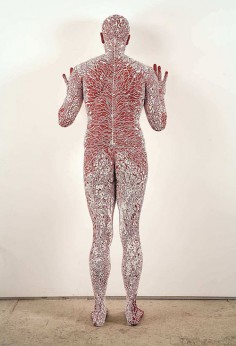

Homeostasis

source: theguardian

Before he left for the last time, Daddy did something bad to Liza Lou. He’d already whacked her around the kitchen for making too much noise, already driven Mom from prayer to the bottle, already whipped and blinded and cut the family dog. No calls to the Lord would drive out those demons. Whatever was done to Mommy’s little Pumpernickel should never happen to a six-year-old. He made her lie obedient on the worktable in the basement, the one where he made some kind of living with his Bible study illustrations. She was blindfolded and in her best dress. Poor Liza Lou.

Born Again is a sorry tale, told in an up-close, 50-minute filmed monologue. The way Lou tells it, her mother had minor roles on Broadway in the 1960s, and lived in a New York loft, below the painter Roy Lichtenstein. She’d hung out at the Factory, she knew Andy Warhol. She met her handsome beau at a cocktail party; married within weeks in a whirlwind romance, they went one night to a Billy Graham revival meeting and were reborn. Not long after they burned all their books, tore up the paintings Lichtenstein had given to Mom, fed their bohemian liberal Manhattan life into the wood-burning stove and booked one-way tickets to small-town Minnesota. As the plane swung away from the coast Mom wept. “Isn’t it wonderful?” she said, emptily. After that they wore their happy born-again Christian smiles and never once looked back.

Liza Lou sings plaintive gospel songs, recalls bitter memories and the blind hypocrisies of a strict, Pentecostal upbringing among the Christian right. She is filmed in a single, static take. But on screen Lou is animated, clambering over the table, leaning into the camera, her face looming in intimacy. She slumps, she croons, she recollects the confusions of her childhood world. There are moments of adult irony and of snot-dribbling tearful anger. She does all the voices. It is a terrific performance, brilliantly framed and choreographed, stark in black and white. Her story and her delivery are funny, harrowing and awful; Liza Lou is a natural performer. Her whole body talks.

Born Again is screened every hour on the hour in a small room, a few doors away from White Cube, where Lou’s first British solo show is installed. Born Again is more than a counterpoint to the strange and at first sight overwrought sculptures and tableaux she has become famous for. How much of her story is gospel truth we’ll never know, but it makes one look at her art differently. “What happened to her, what goes on happening to her, does not account for her work,” writes Jeanette Winterson in the catalogue to the show.

Liza Lou has often been trivialised as the “bead lady”. Her art is distinguished by the thousands of tiny threaded and glued beads that cover every millimetre of her life-sized sculptures and environments. There are those who would see Lou’s work as a kind of extreme and cranky craftwork, an obsessional but minor art. Her most famous piece is a full-scale kitchen, whose counters, cupboards, sink, dishes, tap and even the gushing water are all picked out in chains and whorls of beads. There has been a beaded trailer home and a backyard, every blade of grass a spike of beads. Beaded blankets, beaded portraits of all the US presidents, a beaded toilet bowl with beaded stains, beaded saints, a beaded suicide. When can it ever end? It started when she was in college. If Lou could she’d bead the world.

At White Cube, a chainlink cage of security fencing topped with razor-wire stands in the centre of the gallery. There is no gate, no way in or out. What should appear stark and brutal shimmers: the wire, the steel poles and the chainlink are all iced in glass beads, a strange and sparkling coating. It took a year of work, with a group of 20 Zulu women in Durban, South Africa, where Lou has recently been living, to complete. South Africa, lest we forget, is where the British invented the concentration camp, where black townships were corralled behind fences boiling with wire coils, where gated housing estates keep the wealthy safe behind their perimeter walls and razor-wire. Wire is everywhere. It is impossible not to think of compounds in Bosnia, fences in Palestine, the pens at Guantánamo Bay. Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib were on Lou’s mind. But what does it mean to anoint this object? I have begun to see each bead as but one of a million light-fingered, dextrous touches. One of the women Lou worked with said of the cage that: “We are covering it with love.” Each bead a blessing, then, or a kind of forgiveness.

Perhaps. Is this also how we are intended to think of the big, gnarled branch that sticks out of the gallery wall, above head height, which Lou has called Scaffold? Is this work an invitation to a lynching, or a memory of one? What about the golden noose, dangling above an upturned plastic bucket, which has been installed in a small alcove? Is this a corner of Daddy’s cellar? The bucket bears a beaded safety label: “Warning. Children can fall into bucket and drown.” Not when they’re standing on it to reach for the rope, they can’t. This is called Stairway to Heaven, and reminded me of Robert Gober’s lovingly remade domestic artefacts, all of which carry a sour unease. In the best of Lou’s work, something similar is going on. But love, it strikes me, is not what the beads invoke. What they do instead is create a sense of remove, of unreal presence.

I have a great deal of difficulty with Lou’s figures, which have a very different sense of unreality. I just can’t believe in them. A man, doubled over into some absurd, almost Hieronymus Bosch-like yoga position, balances a knife between his testicles and his mouth. Another, vaguely Christ-like, loinclothed figure, squats, holding up a plank of wood. He has no head; the red tunnel of his trachea disappears down into the darkness of his body. This unrecorded station of the cross is ridiculous and awkward. I could not but think of the gruesome and ultimately laughable statuary one sometimes comes across in Spanish churches.

Lou doesn’t need human figures, not least because they illustrate what is already there. We are the figures in her art – both as spectators, and as witnesses to all those other absent hands that toiled with all those beads, whose trace is everywhere we look. And to the figures who might be lynched, might be behind the wire, might be about to top themselves.

The show really comes unstuck in the gallery upstairs, where a naked figure stands, facing away from us, his hands raised and pressed against the wall. Called Homeostasis, his body is a variegated mosaic of red and white beads, a surface pattern tracing blood flow, heat variations, surging lymph. It is horrible only in a boring, illustrative way. The real problem is that he stands, in the gloom, beside a small inspection slot cut through a false wall built into the gallery. Beyond the wall is a cell, whose proportions are based on the death-row cubicles at San Quentin jail. Standing there, peering into the cell, one emulates the position adopted by Lou’s homeostatic man. I don’t think this is either intended or properly thought through. The cell alone would have been more than enough.

The room beyond the wall is empty, brightly lit by a single strip light. Every detail is tessellated with grey, tan and white beads – the cinderblock walls, the scabrous concrete ceiling, the grouting, the soiled cement flooring, with its alluvial, shit-curdled stains. Even the dangling threads of dust from the ceiling are beaded. The work took years. Lou insisted on using the smallest possible beads, all placed the right way up. Fabricating this work was itself a kind of sentence. I think of each bead as the counting out of each moment in the cell, every heartbeat, each breath, every cough. This, I thought, is somewhere she knows, her own jail.

There is something deathly about this threnody of beads, many so small they had to be handled with tweezers. All those millions of glass and plastic atoms, all that finger-numbing, eye-straining, relentless, painstakingly repetitive work. Lou also decided that the beading should be built up in successive layers, stratified and laminated in beads. During the fabrication of the cell, she allowed no talking among her assistants. You wonder who was being punished here. Right at the end, she hacked away about a year’s worth of work, leaving the cell with a palpable sense of use, damage, lost time, lost lives.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: scpt209

Liza Lou is an American artist who works in Africa and Los Angeles. She’s been part of exhibitions since 1994 and is also a writer. She is best known for working with small beads to complete her works. Liza Lou’s sculptures and environments thrive on the tension between the apparent impossibility of their construction, the seductive beauty of their surfaces and the often sinister implications of their subject matter. Over the past several years, while living and working in South Africa, Liza Lou has developed a body of work based upon further ideas of confinement and protection. Security Fence (2005) is a full-scale, silver beaded enclosure of chain-link and razor wire that can neither be entered nor exited.Her first major work was completed in 1995 and took four years to create. “Kitchen” is a 168-square foot to-scale and fully equipped replica of a kitchen covered in tiny beads. It’s bright, bold and colorful and takes an ordinary kitchen and turns it into an extraordinary art piece.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: refreshblograiit

Un giorno Liza Lou si piegò con pazienza, e con una pinzetta, a coprire di perline ogni superficie di una cucina. Molti la ritenevano un’ossessione, altri una perdita di tempo, ma dopo cinque anni l’artista aveva concluso la sua incredibile Kitchen.

La vita di Liza Lou è complessa da raccontare, dalla torbida infanzia in una famiglia bohemien convertita al fondamentalismo cristiano fino alla scuola d’arte da cui si distaccò per seguire la propria strada.

Ma la sua incredibile arte, inizialmente bollata come “bigiotteria”, continua a stupire e ad incantare fino ad aver fatto meritare a Liza, oltre alle tante esposizioni, il titolo di “genio” (ed il relativo premio) della celebre MacArthur Foundation.

La sua tecnica consiste nell’uso di milioni di piccole perline di vetro con cui ricopre la superficie delle proprie sculture. Tra il 1991 ed il 1996, mentre lavorava alla sua cucina, oltre ad attirarsi le proteste e le irrisioni da parte di insegnanti e compagni di corso si procurò una terribile tendinite. Il suo lavoro successivo, per cui le furono necessari tre anni di paziente lavoro, riproduceva il piccolo giardino che si trova sul retro delle case.

I soggetti di Liza Lou si sono poi evoluti fino a rappresentare temi mistici, classiche opere d’arte (come nel caso di Damned, in cui è facile riconoscere gli Adamo ed Eva di Masaccio), figure umane o luoghi simbolici.

Quello che mi ha colpito del suo lavoro, oltre alla convinzione con cui Liza ha individuato e percorso la propria strada, è il lento respiro del tempo. Pare che l’infatuazione per l’arte abbia colpito Liza Lou durante un viaggio in Italia, nelle maestose cattedrali fiorentine e veneziane: opere per le quali hanno lavorato intere generazioni e che, in alcuni casi, a distanza di secoli non sono state ancora concluse o mancano della facciata. Ecco, quello che trovo in Liza Lou è la totale assenza di paura del tempo. La immagino iniziare un’opera senza la minima preoccupazione dei mesi che impiegherà per completarla, me la figuro rapita dall’ipnotico movimento ritmico con cui aggiunge ciascuna piccola perlina sulle sue sculture. Subito ripenso alla pazienza silenziosa con cui cresce un albero o con cui, cellula su cellula, si costituisce l’organismo di un feto che si prepara all’esistenza.

Forse è un tormentato e doloroso passato a spingere l’artista newyorkese nella realizzazione delle sue sculture e molti critici hanno parlato di inquietudine nella contemplazione delle opere di Liza Lou. Io però mi sento rispondere con emozioni diverse: so, ad esempio, che Liza nasconde piccole poesie o segni infinitesimali ed indecifrabili nei dettagli dei propri lavori. Ed è proprio con una visione ravvicinata che si può apprezzare la sua arte, nell’ordinata geometria della disposizione delle perline che crea disegni simili ad un mandala e comunica una pace straordinaria, riducendo il tempo (e l’ansia che spesso produce in noi) in una divertente collana infinita di perline colorate.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: forblabla

Лиза Лу (Liza Lou) родилась в 1969 году в Нью-Йорке.

Она стала известной, благодаря своей инсталляции «Кухня». Представленная в 1996 году в Нью-Йоркском музее современного искусства скульптура изображала интерьер современной типично американской кухни в натуральную величину, где все поверхности были покрыты миллионами стеклянных бусинок. Чтобы создать эту работу, Лиза потратила пять лет.

Заявив о своей творческой манере широкой публике, художница верна выбранной технике до сих пор. В галереях Америки, Европы, Японии регулярно выставляются скульптурные инсталляции из бисера и стекляруса, в которых Лиза Лу затрагивает актуальные социальные и политические темы, такие как права женщин или расовая справедливость.