RICARDO BARRETO AND MARIA HSU

Avactor

Abstract: fileorgbr

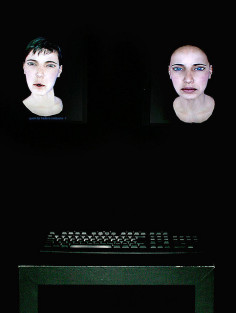

Com a concepção das máquinas abstratas inaugura-se uma nova era, tanto na filosofia quanto na ciência e, acreditamos, também nas artes. O que são máquinas abstratas? Para alguns elas são imanentes e singulares, para outros identificam-se com a própria mente humana. Em ambos os casos compartilha-se a idéia de que o homem é uma máquina. Não somente seu corpo, mas também sua subjetividade. Nesse sentido, Andy Warhol tinha razão ao querer ser uma máquina; entretanto, o filósofo (Gilles Deleuze) e o cientista (Alan Turing) já sabiam que eles próprios eram máquinas abstratas há muito tempo. Penso, logo conecto; penso, logo computo. Estes poderiam ser os novos cogitos daquelas máquinas abstratas. Em suma: Penso, logo sou uma máquina abstrata. Para o filósofo, as máquinas abstratas, independentemente do sujeito, atravessam, numa relação diagonal, todos os planos e todas as disciplinas, criando conexões inauditas entre elas, constituindo a própria criatividade. Para o cientista, elas constituem máquinas universais, algorítmicas e axiomáticas, das quais decorre o surgimento de máquinas de Turing, capazes de imitar qualquer máquina e dando condição para a invenção dos computadores (máquinas concretas, máquinas-objetos). É interessante notar que, tanto para o filósofo quanto para o cientista, o conceito de máquina abstrata é anterior a qualquer máquina concreta, ou seja, anterior à noção de tecnologia, decorrendo daí sua imanência como intenção tecnológica (Leroi-Gourhan). Fica então a questão: se as máquinas abstratas possibilitaram a construção de máquinas concretas, poderiam as máquinas abstratas também produzir a si mesmas? Seriam elas autopoéticas? As máquinas mêmicas parecem comprovar essa tese (Dawkins). A resposta parece ser afirmativa também para aqueles que acreditam na concepção e no desenvolvimento da inteligência artificial. Contudo, esta resposta nos parece parcial, pois neste caso enfatiza-se o lado apenas da inteligência, em detrimento da subjetividade no sentido amplo – inteligência, emoções, volições, desejos -, apesar de pesquisas nesse sentido (Marvin Minsky). Ao invés de nteligência Artificial, deveríamos considerar a disciplina como Subjetividade Artificial. A questão é, de outro modo, a seguinte: podem as máquinas abstratas se replicar, constituindo máquinas-sujeitos de inteligência, de emoções, de volições, de imaginação, de desejos, de sonhos – ou seja, como máquinas de subjetividade artificial? Assim poderemos estabelecer os computadores não apenas como máquinas-objetos para uso da subjetividade natural, mas também como máquinas de subjetividade artificial, de tal modo que as máquinas-sujeitos viessem a operar as máquinas-objetos, o mesmo ocorrendo para os autômatos, os robôs e os avatares digitais. Entretanto, observamos a necessidade de outro elemento, sem o qual a subjetividade artificial não consegue se manifestar. No presente momento, muito mais que um ego artificial ou uma consciência artificial, num sentido estruturante, ela precisa ter, num sentido tático, uma persona ou uma personagem, em suma, um ator. Sem essa persona a subjetividade artificial torna-se apenas uma paisagem, faltando-lhe a referencialidade subjetiva; sem esse ator não há empatia entre a subjetividade artificial e a subjetividade natural. A essa personagem artificial chamamos de Avator. Ele se constitui como pessoa na ação ou interação da subjetividade artificial com a pessoa da subjetividade natural do interator. O termo Avator deriva do termo comumente conhecido por avatar. Avator = avatar + ator. A relação entre o Avator e o Interator pode dar-se por meio da língua de forma dialógica, sem que haja ainda um avatar. Chamamos essa relação de primeira ordem, na qual o avatar é elidido; já na relação de segunda ordem há ao menos um avatar ou avatares (ou autômatos), que medeiam a relação dialógica, óptica e háptica entre as subjetividades natural e artificial. Há também uma relação que poderíamos chamar de ordem “zero”, em que o Avator se relaciona consigo mesmo numa relação reflexiva, mas também uma relação de ordem (-1) menos um, em que o Avator se relaciona com outros Avatores. Diferentemente dos humanos, que somos formatados com um único ego para cada subjetividade natural, parece-nos que a natureza da subjetividade artificial pode se constituir de uma multiplicidade de avatores inter-relacionados (esquizofrenia artificial). Por fim, a relação primitiva do Avator com a máquina-objeto, no sentido de o sujeito-ator artificial operar o funcionamento da máquina-objeto. Ricardo Barreto Nietzsche, o primeiro Avator Por que não conversarmos hoje com um personagem de Dostoievsky ou com um pensador de outro século? Escolhemos então alguém fascinante e controverso, que provocou a ruptura total, criticou todas as verdades da civilização ocidental: Nietzsche. De quê este personagem necessita para viver? Ele necessita de uma forma concreta, uma face, uma voz, uma fala, enfim, um avatar e uma anima, uma inteligência. Partimos então em busca de ferramentas para criar a face virtual: esculpir as formas tridimensionais, adicionar as texturas e cores para materializar a beleza e as imperfeições, introduzir expressões faciais como um olhar um pouco mais arrogante, um ar mais distraído ou misterioso, ou feliz ou angustiado. Quanto à voz, entre uma leitura dramática ou sintética, embora com uma clara perda de dramaticidade, optamos pela voz sintética e obtivemos desta forma uma automação total de nosso avator. Modulamos a voz em língua portuguesa, mais ou menos límpida, sua velocidade e suas pausas. A fala exige uma sincronização perfeita com os lábios, além da obtenção dos movimentos naturais da cabeça. Toda essa extensa lista de detalhes foi superada devido ao trabalho integrado multidisciplinar entre artistas e matemáticos. O avatar de Nietzsche seria uma obviedade se fosse a face de um homem maduro com o grande bigode característico. No entanto, interessa-nos manifestar que não pretendemos reproduzir uma imagem à semelhança de Nietzsche e ousamos confeccionar um avatar com forma feminina. O segundo grande bloco de desafios na execução foi o de propiciar uma inteligência que permita a interação com o interator. O avator foi então construído em um ambiente de inteligência artificial que permite a interação entre o avator, Nietzsche, com o interator, o público. Embora ele tenha um pequeno desejo de interagir em assuntos do cotidiano, seu maior interesse são as discussões filosóficas. Se Nietzsche se funde ao seu avatar, gerando um avator, por que não oferecer o mesmo para seu interlocutor? Criamos então um segundo avatar para se fundir ao interator, fazendo assim uma distinção para o público entre o que é avator-avatar e avatar-interator O trabalho permanece em contínua elaboração. À medida que transcorre a mostra, as interferências do interator vão sendo incorporadas. Nietzsche buscará refletir sobre as perguntas mal respondidas, assim como assimilará algumas idéias introduzidas.

Biography:

Ricardo Barreto é artista e filósofo. Atuante no universo cultural trabalha com performances, instalações e vídeos e se dedica ao mundo digital desde a década de 90. Participou de várias exposições nacionais e internacionais tais como: XXV Bienal de São Paulo em 2002, Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) London – Web 3D Art 2002, entre outras. Concebeu e organiza juntamente com Paula Perissinotto o FILE – Festival Internacional de Linguagem Eletrônica.

Maria Hsu tem se dedicado às Artes Visuais experimentando pintura, fotografia e arte digital. Também tem um interesse em Filosofia. Anselmo Kumazawa formou-se em Ciências de Computação em 1999 na Universidade de Sao Paulo onde está concluindo o seu curso de pós-graduação. Além do interesse em Arte Digital, ele é um gerente de desenvolvimento em um projeto de E-learning.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: fileorgbr

Abstract:

With the conception of abstract machines, a new era is inaugurated, as much in philosophy as in science and, we believe, also in the arts. What are abstract machines? For some, they are immanent and singular, for others they identify with the very human mind. In both cases one shares the idea that man is a machine. Not only his body, but also his subjectivity. In that sense, Andy Warhol was right in wanting to be a machine; however, the philosopher (Gilles Deleuze) and the scientist (Alan Turing) had known for a long time that they were abstract machines. I think, therefore I connect; I think, therefore I compute. These could be the new cogitos of those abstract machines. In sum: I think, therefore I am an abstract machine. To the philosopher, abstract machines, independently of the subject, cross in a diagonal relationship all planes and all disciplines, creating unprecedented connections among them, constituting creativity itself. To the scientist, they constitute universal machines, algorithmic and axiomatic, from which derives the emergence of the Turing machines, capable of emulating any machine and allowing the invention of computers (concrete machines, object-machines). It is interesting to notice that, both to the philosopher and to the scientist, the concept of an abstract machine precedes any concrete machine, that is, it precedes the notion of technology, from there deriving its immanence as a technological intention (Leroi-Gourhan). But the question remains: if abstract machines have allowed the construction of concrete machines, would they also be able to produce themselves? Would they be autopoetic? The memic machines seem to confirm this thesis (Dawkins). The answer seems to be equally affirmative for those who believe in the conception and in the development of artificial intelligence. However, this answer seems partial to us, because in this case just the side of intelligence is emphasized, in detriment of subjectivity in a wider sense – intelligence, emotions, volitions, desires -, in spite of research in that sense (Marvin Minsky). Instead of Artificial Intelligence, we should consider the discipline as Artificial Subjectivity. Put in another way, the question is: can abstract machines replicate, constituting subject-machines of intelligence, motions, volitions, imagination, desires, dreams – that is to say, as artificial subjectivity machines? Thus, we could define computers not only as object-machines for the use of natural subjectivity, but also as machines of artificial subjectivity, in such way that the subject- machines would operate the object-machines, the same happening for automata, robots and digital avatars. However, we observe the need of another element, whose absence prevents artificial subjectivity’s manifestation. In the present moment, rather than an artificial ego or an artificial conscience, in a structuralizing sense, it must have, in a tactical sense, a persona or a personality, in sum, an actor. Without that persona, artificial subjectivity becomes a mere landscape, lacking subjective referential; without that actor, there is not empathy between artificial subjectivity and natural subjectivity. We call that artificial personality Avactor. He is constituted as a person in the action or interaction of artificial subjectivity with the person of the interactor’s natural subjectivity. The term Avactor derives from the term generally known as Avatar. Avactor = avatar + actor. The relationship between Avactor and Interactor may happen through a dialogic-form language, without being an avatar yet. We call that a first-order relationship, in which the avatar is suppressed; however, in the second-order relationship there is at least one avatar, or avatars (or automata), that mediate the dialogic, optical and haptic relationship between natural and artificial subjectivities. There is also a relationship that we could call of “zero” order, in which the Avactor relates with itself in a reflexive relationship, but also a relationship of minus one order (-1), in which the Avactor relates to other Avactors. Differently from humans, who are formatted with one only ego for each natural subjectivity, it seems to us that the nature of artificial subjectivity may be constituted of a multiplicity of interrelated Avactors (artificial schizophrenia). Finally, the primitive relationship of the Avactor with the object-machine, in the sense that the artificial subject-actor operates the object-machine. Ricardo Barreto Nietzsche, the first Avactor Why don’t we talk today with a character by Dostoievsky or with a thinker from another century? So we chose someone fascinating and controversial, who provoked a complete rupture, who criticized all truths of Western civilization: Nietzsche. What does this character need to be alive? He needs a concrete form, a face, a voice, a speech, finally, an avatar and an anima, an intelligence. Thus we went in search of tools to create the virtual face: sculpting the three-dimensional forms, adding textures and colors to materialize the beauty and the imperfections, introducing facial expressions as a somewhat arrogant glance, a more distracted or mysterious, happy or anguished air. As to the voice, between a dramatic or a synthetic reading, and though with a clear loss of drama, we chose the synthetic voice, and so achieved a complete automation of our avactor. We modulated the voice in Portuguese, a more or less limpid language, its speed and its pauses. Speech demands a perfect synchronization with he lips, besides obtaining natural head movements. That whole list of details was overcome thanks to an integrated multidisciplinary work of artists and mathematicians. Nietzsche’s avatar would be obvious if he had the face of a mature man with the big typical mustache. However, we want to make clear that we didn’t intend to reproduce an image to the likeness of Nietzsche, and we dared to make an avatar with a feminine form. The second great block of challenges in the execution was that of propitiating an intelligence, which allows interaction with the interactor. The avactor was built, thus, in an atmosphere of artificial intelligence that allows the interaction between the avactor, Nietzsche, and the interactor, the public. Although he has a small desire of interacting in day-to-day matters, his main interest are philosophical discussions. If Nietzsche is assimilated to his avatar, generating an avactor, why not to offer the same to his interlocutor? We created then a second avatar to fuse with the interactor, thus making a distinction for the public between what is avactor-avatar and avatar-interactor. The work remains in continuous elaboration. As the exhibition goes on, the interactor’s interferences are incorporated. Nietzsche will try to reflect on questions that were badly answered, as well as he will assimilate some of the ideas introduced.

Biography:

Ricardo Barreto is both an artist and a philosopher. Active in the cultural scene, he work with performances, installations and videos. He has been working with digitalization since the nineties. He has also taken part in several national and international exhibitions such as: XXV Biennial of São Paulo in 2002; Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) London – Web 3D Art 2002. He also conceived and organized together with Paula Perissinotto the international FILE – Electronic Language International Festival.

Maria Hsu has been dedicated to Visual Arts experiencing the following midia: painting, photography and digital art. She has also an interest in phylosophy. Anselmo Kumazawa graduated in Computer Sciences in 1999 at Sao Paulo University where he is concluding his post graduate studies. Besides his interest in Digital Art, he is the development manager in an E-learning project.