SIMON STARLING

سيمون ستارلينغ

西蒙·斯塔林

サイモン·スターリング

사이먼 찌르레기

Саймон Старлинг

The Mirror Room

source:

‘Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima): The Mirror Room’, The Modern Institute, Osborne Street, Glasgow, 20/11—17/12/2010

SIMON STARLING

Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) / Mirror Room

The Modern Institute is pleased to present Simon Starling’s exhibition Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima): The Mirror Room.

This is the first part of a two-part exhibition to be realized at The Modern Institute, Glasgow and Hiroshima City Museum, where Simon will exhibit in January 2011. The Mirror Room of the title refers to the dressing room in a traditional Japanese Noh theatre where the actors fit their masks and are ritually possessed by the characters they will perform on the adjacent stage. It is a space in which identities are traded, in which ghosts assume human form , men are transformed into women, the young become old, and the old young.

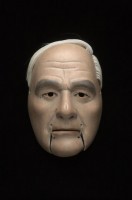

The exhibition at The Modern Institute presents nine characters in the form of six carved wooden masks, two cast bronze masks and a hat*. This cast of characters has been assembled for the proposed performance of a 16th century Noh play, Eboshi-ori, the story of a young noble boy who, with the help of a hat maker, disguises himself to escape enforced exile and begin a new life in the east of Japan. When populated by the assembled cast, this tale of personal reinvention, serves to mirror the complex Cold War saga that surrounds the double life of Henry Moore’s multifaceted sculpture Atom Piece (1963-65).

*Note: the carved wooden masks where made by Yasuo Miichi, a master mask maker from Osaka, Japan. The bowler hat or coke is an exact replica of one made in 1964 by Lock and Company, London, for the actor Harold Sakata.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: frieze

In Simon Starling’s Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima): Mirror Room (2010), the sculpture’s various histories are collapsed into one polyvalent narrative (the exhibition toured from The Modern Institute to the Hiroshima City MOCA, where it is currently showing). Conflating references to Japanese Noh theatre, the Manhattan Project, Goldfinger (1964) and the Cold War-era art world, the installation comprises eight masks and a single hat (a replica of Goldfinger’s henchman Odd Job’s lethal steel-rimmed bowler) mounted like heads on anthropomorphic iron tripods (a booklet with the back-story also accompanies the exhibition). These objects tell a story based on Eboshi-ori, a 16th-century Noh play in which a young noble boy (named Ushiwaka) disguises himself to escape enforced exile and begin a new life in the east of Japan. Starling, however, assigns each role to one of the players in the Nuclear Energy saga – a motley crew of objects and personages, both real and fictional.

Nuclear Energy itself is given the role of Ushiwaka, the protagonist from Eboshi-ori. Moore is cast as the milliner who disguises the young boy by making him a highly encoded eboshi hat. The art historian and Soviet spy Anthony Blunt is given the role of the hat-maker’s wife, who in the Noh drama reveals a startling secret past. (Blunt was also a staunch supporter of Moore. A second Moore sculpture features among the players: Warrior with Shield (1953–4), which was purchased by the Art Gallery of Ontario on the recommendation of Blunt.) Fast-food icon Colonel Sanders plays the Innkeeper, who welcomes Ushiwaka and warns him of imminent danger. (As the face of the KFC franchise, Sanders serves as a representation of American influence in Japan; KFC also makes an appearance in Goldfinger, in a scene set in Fort Knox, Kentucky.) In the role of the opportunistic bandit Kumasaka is Joseph Hirshhorn, the multimillionaire-cum-voracious art collector, who owned dozens of works by Moore and whose wealth was derived from uranium mining (the ore of which was used to produce nuclear weapons). In Eboshi-ori, the bandit Kumasaka is fought off by a gold merchant, Kichiji. Starling assigns this role to James Bond himself, as portrayed by Sean Connery in Goldfinger, who poses as a gold merchant to ensnare the film’s eponymous villain.

Handcrafted by Yasuo Miichi, a master mask-maker from Osaka, the carved wooden masks make Starling’s spatial and temporal compressions visually manifest. They are amalgams: their assigned identities are uncannily recognizable, yet they also look like traditional Noh masks, with real hair and meticulously applied pigment. Connery (as Bond) is given Asiatic eyes, arched brows and a bow-shaped mouth; Blunt is depicted with delicate feminine features, his eyes closed with only narrow slits for peep holes (characteristic of female Noh masks); Hirshhorn is shown as a fiery demon, with a face like a furious Fu dog (similar to the Kijin-kei, or Fierce God, type of Noh mask). Starling risks losing the viewer with these strange recontextualizations, but the work has striking visual impact, as arcane references coalesce into an elegant, minimal installation. Like an iceberg, the narrative is mostly submerged, with the physical installation only alluding to the depth of Starling’s discursive process as elucidated in the exhibition guide.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: listcouk

The pan-global plot of Simon Starling’s latest work is as labyrinthine as a Cold War spy thriller. The quiet elegance of the GSA-trained 2005 Turner Prize winner’s Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) / Mirror Room similarly references both real and imagined history to highlight events relating to an ongoing East-West divide. Taking in everything from a Henry Moore sculpture to Japanese Noh plays and James Bond to art historian-turned-Russian spy Anthony Blunt, the show is a complex sculptural meditation that takes us backstage to witness an array of individually carved masks and imagine the actors inhabiting their characters before the real drama begins next year on the other side of the world.

‘It’s kind of the first part of an exhibition that will take place later in Hiroshima,’ says Starling down the line from Copenhagen, where he’s lived with his family for the last five years. ‘The Glasgow part is sort of an ante-chamber to the second exhibition.’

Starling’s mission impossible goes something like this. While researching Moore’s work for his own ‘Infestation Piece (Musselled Moore)’, first shown in Toronto in 2008, Starling became fascinated by Moore’s 1965 ‘Nuclear Energy’, commissioned to commemorate the site of the first nuclear reactor in Chicago. This had grown out of ‘Atom Piece’, commissioned by Hiroshima museum two years earlier. When Starling was approached by the same institution, his imagination was fired by assorted conspiracy theories involving CND posters, political intrigue and the lingering diplomatic fallout over the American bombing of Hiroshima in 1945.

Turning to a 16th century Noh play about an aristocratic boy escaping in disguise from a Buddhist temple aided by a local milliner, Starling began work with a Noh mask-maker in Osaka to create images featuring a star-studded cast that includes KFC founder Colonel Sanders, Sean Connery’s Bond circa Goldfinger as – what else? – a gold merchant, and Blunt as the hat-maker’s wife.

‘It’s looking at these things in a playful way,’ Starling says, ‘but using this ancient and incredibly intricate artform.’

In Hiroshima next year a film will be shown of the masks being made, although given the West’s long-standing fascination with Noh aesthetics by theatrical auteurs including Bertolt Brecht, Peter Brook and Robert Lepage, the logical next step would be to see Starling’s vision staged.

‘It would be interesting if that did happen,’ says Starling, ‘but I’m not sure how possible that would be. The mask-maker’s art is an incredibly entrenched form that remains belligerently unchanged. His job is to make masks for specific actors, so for him to step out of this very small Noh community for this show is incredibly brave.

‘Before the masks are painted, the mask maker writes little messages inside them that personalises them in some way. On one of the masks he wrote in Japanese something along the lines of “Ban the Bomb”. I didn’t ask him to do it, but he was very happy about it.’

The plot, as they say, thickens.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: art-itasia

2011年上旬、サイモン・スターリングの個展『仮面劇のためのプロジェクト(ヒロシマ)』[注1]が広島市現代美術館で開幕した。同名の新作は、能の謡曲『烏帽子折』(宮増作、16世紀初頭)のために、従来の登場人物にイギリス人彫刻家ヘンリー・ムーアや革新的な原子核物理学家のエンリコ・フェルミらを割り当て、一連の新しい能面の制作を能面師に依頼するというものだ。その中で、冷戦時代の陰謀、ジェームズ・ボンドのようなキャラクターや美術史を連関させていく。完成した能面は天井から吊られた鏡の前に配置され、その鏡の裏側にあたるスクリーンに能面の制作の様子をとらえたドキュメント映像が投影される。

本作を以てスターリングは、能面と能面との間に複雑に入り組んだ、何層も重なり合う複数の物語を織り込むことにより、能と現代彫刻というふたつの様式化された表現方法の限界に挑み、それぞれの表現方法の意味を伝達する能力を拡大すると同時に反証をも挙げている。

欧米と日本との全く異なる文化からの引用を操作する創意とデリカシーと、純然たる存在感とコンセプトレベルでの巧みな転覆との組み合わせとによって、「仮面劇のためのプロジェクト(ヒロシマ)」は2011年に最も印象的だったプロジェクトのひとつとなった。今回の年末特集の一環として、展覧会の際に広島で行なったサイモン・スターリングとのインタビューを以下に収録する。なお、同日に行なわれたアーティストトークにて、「仮面劇のためのプロジェクト(ヒロシマ)」の前で語られた内容も抜粋し別途掲載する。

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: groupelaurafreefr

Plus qu’un créateur de formes, l’artiste britannique Simon Starling est un conteur : il revisite l’histoire, crée des ponts entre différentes valeurs et catégories, propose un regard nouveau sur ce que nous avons perdu l’habitude de remettre en question. Les installations et les processus qu’il met en place sont autant de manières de se réapproprier le passé, de s’introduire dans des systèmes a priori fermés, d’y replacer de la subjectivité afin de modifier notre rapport au monde et tenter de nous ressaisir… de notre présent.

1995 – An Eichbaum Pils Beer Can found on the 6th April 1995 in the grounds of the Bauhaus, Dessau, and reproduced in an edition of nine using the metal from one cast aluminium chair designed by Jorge Pensi : Simon Starling utilise l’aluminium d’une chaise conçue par le designer argentin Jorge Pensi afin de réaliser une série de neuf canettes de bière, sur le modèle d’une canette trouvée sur le site du Bauhaus à Dessau.

1997 – Blue Boat Black : l’artiste fabrique une barque avec le bois provenant d’une vitrine d’exposition du Musée National d’Ecosse à Edimbourg. Durant son voyage de Glasgow à Marseille, il pêche une dizaine de poissons qu’il fera ensuite griller avec la braise de la barque brûlée. Les reliques de l’action seront ensuite exposées. 1997 – Work, Made-Ready, Kunstalle Bern : une chaise de Charles Eames (l’un des pionniers du design moderne) est répliquée à partir de l’aluminium d’un VTT Sausalito, et inversement : un VTT est reconstruit avec l’aluminium d’une chaise de Eames.

2000 – Rescued Rhododendrons : dans le cadre d’une commande publique, des artistes sont invités à proposer des projets de sculpture sur une lande de bruyère en Ecosse. Apprenant que les rhododendrons qui poussaient sur cette lande allaient être détruits afin qu’ils ne nuisent pas à l’écosystème, Simon Starling entreprend de sauver les rhododendrons, considérés là-bas comme de la mauvaise herbe, et de les rapporter sur leurs terres d’origine, dans le sud de l’Espagne. (Les rhododendrons avaient en effet été importés d’Espagne en Ecosse en 1763, par un botaniste suédois, à l’époque où l’horticulture prenait naissance et était associée à l’idéologie de la colonisation – exhibition des plantes exotiques). Starling décide donc de renverser le processus en transportant des rhododendrons, dans sa Volvo (voiture suédoise), du nord de l’Ecosse au sud de l’Espagne.

A travers les installations, les performances et les processus complexes qu’il met en place (dont ceux décrits ci-dessus ne sont que quelques exemples), Starling créé des hyper-liens qui mettent en relation des espaces, des temps, des histoires et des cultures différents. Les objets sont fondus, transformés, reconstruits, de la même manière que situations et contextes sociaux, économiques ou esthétiques se voient remodelés, déplacés ou reliés soudainement les uns aux autres. En traversant les frontières comme les époques, l’artiste impulse des mouvements et des principes de mutation qui parviennent à reconfigurer à la fois l’appréhension de l’histoire et celle de l’expérience quotidienne.

En général, Starling se passe d’inventer de nouvelles formes ou de nouveaux objets : il créé des relations, rassemble des fragments, fait jouer entre elles des valeurs existantes, impose des structures à des événements qui sans lui ne seraient pas nécessairement mis en relation. Ce qui pourrait néanmoins passer pour du ready-made – voir par exemple la chaise de Eames, le VTT, les canettes de bière – est en fait du “ remade ”, du refait, du refondu, un travail d’artisan que précisément Duchamp entendait bannir – l’artiste pervertissant ainsi la valeur d’usage et la valeur d’exposition, réduisant l’écart entre des objets dits de valeur et des objets de consommation de masse. Mais se jouant finalement aussi bien du ready-made duchampien que du mythe du savoir-faire de l’artiste qui, en l’occurrence, ne produit rien d’autre que des répliques d’objets industriels. Sur ce dernier point, Starling ranime les positions du mouvement britannique “ Arts and Crafts ”, et plus généralement la problématique art – industrie propre à la fin de l’époque victorienne : quand il s’agissait de saisir à quel point la révolution technologique avait transformé les modes de fabrication et de diffusion des produits manufacturés ; de tenter de concilier l’art traditionnel et les nouvelles possibilités offertes par l’industrie. En rapprochant sa propre activité d’artiste à celle de l’artisan, en jouant sur le statut des objets, les faisant changer de contexte ou de matériaux, les déplaçant, les métamorphosant et les recyclant, Starling rend confuses les distinctions entre production industrielle, manufacture et métier ; il parvient aussi à questionner la légitimité des systèmes qui créent les catégories et attribuent les valeurs (économiques autant que culturelles), l’institution muséale en tête ; en délivrant l’art de l’artistique, et les objets de leur quotidienneté, il réactive en outre l’utopie des années 50 et 60 qui voulait considérer l’art comme une activité non séparée de la vie.

Prenant le contre-pied du principe avant-gardiste de la rupture, la démarche de Starling repose, on le voit, sur l’établissement de ponts historiques, sociaux et culturels : tout est affaire d’échos, de renvois et de réminiscences. De la modernité, l’artiste réévalue les impacts, ralentit le temps, comprime les espaces, trouble les mécanismes et s’engouffre dans les béances afin de créer des micro-utopies au sein de la macro-histoire, afin de s’accorder des marges de manœuvre à l’intérieur de ce qui apparaît comme un déterminisme. Il revisite les catégories inhérentes à l’esprit moderne marqué par la rationalité unitaire et progressiste, confiant dans une vérité système. Il substitue aux grands récits totalisateurs des micro-récits qui s’appuient sur la prolifération des réseaux de communication, sur l’aléatoire et la discontinuité afin de créer des jeux multiples et autant de nouvelles perspectives sur le réel.

Starling réorganise le monde, à sa guise, mais sans la prétention de l’artiste romantique : en privilégiant l’amateurisme, en refusant la maîtrise et la perfection, en abordant, à la manière de Bouvard et Pécuchet, des activités extrêmement diverses et fragmentées… Et si ces processus sont inscrits, à chaque fois, dans des contextes économiques, culturels et esthétiques précis, issus de recherches longues et laborieuses, c’est sans doute aussi pour faire apparaître la poésie du jeu, du détour ; et le temps infini de la rêverie…