ERWING HAUER AND ENRIQUE ROSADO

2008

source:digitalartarchivesiggraphorg

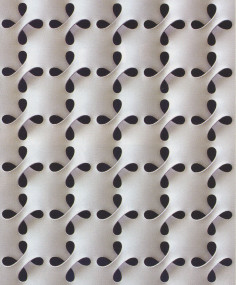

The concepts of continuity and potential infinity have been central themes of Erwin Hauer’s opus from very early on in his career as a sculptor. In his native Vienna, he began to explore infinite continuous surfaces that evolved into perforated modular structures that were appropriate in architectural applications. Hauer’s sculptural walls are intricately woven forms that create a visual sense of infinity – a frozen poetry in motion. He patented these designs, developed the technology to produce them, and installed the modular, light-diffusing walls in buildings throughout the United States and seven other countries.

Hauer continued this work after he moved to the US, first as a Fulbright scholar and then as a faculty member in the Department of Design at Yale University, where he was invited by Josef Albers, a giant of modernism and one of the pillars of the Bauhaus.

Hauer derived the concept of continuous surface primarily from his studies of biomorphic form, an experience reinforced by his first encounters with the work of Henry Moore. He examined how Moore interlaced “… the dominant continuity of surfaces with an unprecedented cultivation of interior spaces within his sculptures.” These reflections led Hauer to the awareness of the so-called saddle surface, a type of mathematical surface that looks like the peculiar shape of horse saddles that curve both up and down. These surfaces influenced his sculptures and soon evolved into a repeat pattern because, as Hauer states, “the saddle surface refuses to permit the closure of form.” While Naum Gabo accepted this fact, Hauer responded to the open-endedness of the single saddle by adding replicas of it around its boundaries, in a seamless and flush manner. When this procedure is repeated for every open-ended edge, the result is in an infinite continuous surface. This characteristic is central to most of Hauer’s screen designs.

In 2003, Hauer formed a partnership, Erwin Hauer Studios, with Enrique Rosado, a former student of his at Yale who has extensive knowledge in the digital field. Their purpose is to re-issue a selection of Hauer’s original screens of the 1950s, to adapt some of these classic designs to modern production methods using digital technology, and to develop new designs as well. With the same intensity and scrutiny Hauer applied to his original molds and casts, Enrique Rosado now focuses on design transformations, creation of custom tools, and CNC-milling techniques.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source:architectureyaleedu

“Beginning in 1950, very early during my studies in sculpture, I developed a series of works that were modular in structure and featured surfaces that were continuous. They also showed the potential for continued progression toward infinity.“

This is Erwin Hauer (1926-2017) describing the development of the first Continua, the modular planar sculptures that launched his career. The Austrian-born sculptor would go on to patent these designs, develop the technologies to manufacture them and install several screen walls based on the designs for churches in Vienna. Based on the attention these screens generated, he was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship and came to the United States in 1955. Josef Albers invited him to join the faculty of Yale in 1957 where he taught until 1990. Hauer’s patented designs for the Continua were licensed to the New York firm Murals Inc. and marketed throughout the United States and six other countries. The light-filtering screens were embraced and used as brise soleil and room dividers by modern architects including Edward Durell Stone, Gordon Bunshaft, and Florence Knoll. After about twelve successful years, the manufacture of the architectural screens ceased due to changing market conditions.

Hauer continued to work as an independent sculptor in Bethany, Connecticut. During this period, he furthered his work with double curved or “saddle surfaces”, begun in the 1950s, but now advancing out of the plane into what he called “fully three-dimensional modules that potentially propagate throughout all of space.” These modules, which he happened upon intuitively, were later acknowledged as a mathematically significant achievement and given the name I-WP surfaces by the mathematician Alan Schoen. This line of inquiry led Hauer through numerous variations on encapsulating infinite space within finite formal configurations. These sculptures include small studies as well as tall towers and are rendered in a range of materials.

With the publication of Erwin Hauer: Continua in 2004 by Princeton Architectural Press, there was renewed interest and demand for Hauer’s modular installations. Hauer teamed up with his former student Enrique Rosado to produce some of his earlier designs and to adapt his Continua screen walls for production with computer assisted techniques. They remain in production in New Haven today.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source:hardecorcombr

Os painéis modulares de Erwin Hauer, nascido em 1926, começaram a ser confeccionados na década de 1950 na Austria, terra natal do escultor/designer. Depois de instalar suas peças em várias igrejas em Viena, Hauer foi convidado a ir para os EUA para lecionar na Rhode Island School of Design, e logo após, mudou-se, a convite de Josef Albers para a Yale University, onde permaneceu por mais de três décadas. Considerados uma pérola do modernismo, os painéis de Hauer foram usados em obras importantes no Brasil pelos arquitetos Marcio Kogan e Kiko Salomão, que entrevistou pessoalmente o designer em seu estúdio em New Heaven, EUA, e ficou bem impressionado com a vitalidade e sabedoria de Hauer, na época com mais de 80 anos. Depois de quase duas décadas sem produzir, o designer e seu pupilo e ex-aluno Enrique Rosado recolocaram o produto no mercado, agora fabricado segundo a mais moderna tecnologia. Encante-se!