LEBBEUS WOODS

Леббеус Вудс

レベウス・ウッズ

san francisco project

source: onlinewsj

‘Lebbeus Woods, Architect” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art articulates several reasons why this cultish figure (1940-2012) deserves to be better known yet, perhaps without meaning to, also suggests as many reasons why he isn’t.

The two rooms of drawings, models and theoretical writings offer a hypnotic portrait of an American out of step in his later years with his age and profession. A space-age philosopher more enamored of the incredible than the doable, closer in his own view to a malcontent firebrand like Friedrich Nietzsche than to any of his contemporaries, he seems to have spent more time as an adult composing aphorisms and manifestos than going about the tedious business of winning commissions or seeing that his fantastic schemes were actually realized. He leaves behind almost nothing that any of us will ever walk through.

Joseph Becker and Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, assistant curators in the Architecture and Design department, plunge the visitor immediately into the stormy world view of a thinker who once declared that “architecture and war are not incompatible. Architecture is war. War is architecture. I am at war with my time, with history, with all authority that resides in fixed and frightened forms.”

Neither the introductory wall text nor materials in the rooms provide any biographical data. One would never suspect that this iconoclast was a self-described “military brat” from Lansing, Mich., who began his career in the 1960s along a traditional path, in the office of Kevin Roche at Eero Saarinen & Associates, and ended up for several decades as a professor of architecture at Cooper Union in New York. Rather than trace the evolution of his thought, the curators have tried to unhusk the kernels of it, at least as revealed in his major post-1975 projects.

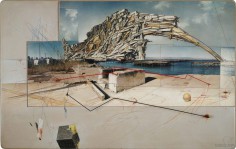

This approach has some advantages. He is presented as his ideas alone. On one side of the first room is a suite of 16 sumptuous drawings from his 1987 “Centricity” series. This futuristic vision of what appears to be a colony for a planet other than ours—in colored pencil, ink and sepia wash—is done in the calligraphic hand of a fastidious draftsman. It is easy to see why museums treat him as an accomplished artist, and why his imaginings, full of romantic ardor for all of their constructivist vocabulary, bring to mind Etienne-Louise Boullée, Giovanni Battista Piranesi and Vladimir Tatlin, as well as Henri de Montaut’s illustrations for Jules Verne’s novels.

On the other side of this entry room are Woods’s 1988 plans and model for the “Einstein Tomb,” an orbiting spacecraft in the shape of a cruciform cenotaph that would have carried the physicist’s ashes throughout the universe, were they not already scattered on the Atlantic Ocean.

Instability was an accepted feature in the architecture Woods developed in the 1980s and ’90s, and he believed that the places we inhabited should reflect this uncomfortable fact. The long main room of the exhibition contains plans from the 1990s for Berlin, Zagreb and Sarajevo in which he argued that these war-torn cities not be tidied up. The rifts of history should instead be reflected in the buildings. A drawing of a Sarajevo building from his “War and Architecture” series has left—or perhaps expanded—the riven facade so that a section protrudes in layered folds, like the tissues of an open wound.

What is missing from the show is any context for Woods’s unorthodox ideas. This is no doubt a deliberate attempt to honor his memory by presenting his work undiluted, without the usual trappings of art history. And it may be just as well that the curators don’t explore the imprint of French literary theory on American architecture in the 1970s and ’80s.

But there is no mention on the walls that Woods co-founded the Research Institute for Experimental Architecture or even that he was a deeply respected teacher. He is described as having had an “enormous influence” on the field. But how, why or on whom is left for the viewer to puzzle out. Only in the sketchbooks from 1998-2002 does one read the names of other New York or European architects (Peter Eisenman, John Hejduk, Aldo Rossi) who were contemporaries of Woods. However much of a maverick he may have been, these dreams did not pop into his head ex nihilo.

The curators present his ideas without a murmur of dissent or skepticism. His program of a new architectural outline for San Francisco, one that would not resist earthquakes but use their destructive energy to create new kinds of structures, sounds marvelous. Until one reflects that mutating architecture would likely be worse than the ills it seeks to cure. The son of a military engineer, he was oddly shy about mechanical specifics. “Einstein Tomb,” Woods mischievously submitted, would be transported throughout the heavens on a beam of light.

Not surprisingly, his thinking has been welcomed in film design and science fiction, where the laws of physics and finance can be overcome with CGI or words on a page. His rhetorical skills sometimes got the better of him. He wrote a lot of high-flown nonsense, such as “changing the way people change means changing the rules of change.” Like most utopians, even ones like himself who pledged allegiance to a bottom-up democratic politics, he could not help sounding at times authoritarian.

It is somehow fitting that the only Woods project that the architect lived to see realized was the 2011 “Light Pavilion”—a complex hole, really—within the Steven Holl-designed Raffles City Center in Chengdu, China. Planned in collaboration with the architect Christoph A. Kumpusch, it is a void crisscrossed by columns and stairs and illuminated from inside. As Woods wrote: “The space has been designed to expand the scope and depth of our experiences. That is its sole purpose, its only function.”

While many of his theory-besotted colleagues from the 1970s and ’80s—Messrs. Holl and Eisenman, and Daniel Liebeskind—went on to impressive careers, Woods was unable to make the compromises often required to build in the real world. “I’ve always worked, more or less—except in certain moments—alone,” he said in 2007.

In this intriguing exhibition, and in the moving tributes by his friends Mr. Holl and Sanford Kwinter (available on Youtube), one sees the lasting value, and the folly, of an architect pursuing such a devout and solitary life.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: sfmomaorg

Architect Lebbeus Woods (1940-2012) dedicated his career to probing architecture’s potential to transform the individual and the collective. His visionary drawings depict places of free thought, sometimes in identifiable locations destroyed by war or natural disaster, but often in future cities. Woods, who sadly passed away last year as planning for this exhibition was under way, had an enormous influence on the field of architecture over the past three decades, and yet the built structures to his name are few. The extensive drawings and models on view present an original perspective on the built environment — one that holds high regard for humanity’s ability to resist, respond, and create in adverse conditions. “Maybe I can show what could happen if we lived by a different set of rules,” he once said.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: wired

He envisioned underground cities, floating buildings and an eternal space tomb for Albert Einstein worthy of the great physicist’s expansive intellect. With such grand designs, perhaps it’s not too surprising that the late Lebbeus Woods, one of the most influential conceptual architects ever to walk the earth, had only one of his wildly imaginative designs become a permanent structure.

Instead of working with construction and engineering firms, Woods dreamed up provocative creations that weren’t bound by the rules of society or even nature, according to Joseph Becker and Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, co-curators of a new exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art titled Lebbeus Woods, Architect.

“It was almost a badge of honor to never have anything built, because you were not a victim of the client,” Becker told Wired during a preview of the fascinating show, which opens Saturday and runs through June 2. While not a full retrospective of Woods’ career, the exhibit shows off three decades of his work in the form of drawings, paintings, models and sketchbooks filled with bold ideas, raw concepts and cryptic inscriptions. (See several examples of Woods’ work in the gallery above.)

As the curators discussed Woods’ work and his impact on the world of architecture, they talked of a brilliant mind consumed with disruption, with confronting the boring, repetitive spaces humans have become accustomed to living in by challenging the “omnipresence of the Cartesian grid.” Woods’ fantastic visions included buildings designed for seismic hot zones that might move in response to earthquakes, or a sprawling city that would exist underneath a divided Berlin, providing a sort of subterranean salon where individuals from the East and West might mingle, free from the conflicting ideologies of their governments.

“He was very focused, I think, in all of his work, in what he said was ‘architecture for its own sake,’” Becker said. “Not architecture for clients, not architecture that is diluted, and not architecture that really had to be held up against certain primary factors, including gravity or government.”

Woods found his place in the conceptual architecture movement that sprang from the 1960s and ’70s, when firms like Superstudio and Archigram presented a radical peek into a possible — if improbable — future. Casting a skeptical eye on the way humans lived in cities, these conceptual architects were more interested in raising questions than in crafting blueprints for buildings that would actually be built of concrete, steel and glass.

In fact, only one of the nearly 200 fascinating drawings and other works on display in Lebbeus Woods, Architect was ever meant to be built, said Dunlop Fletcher. Instead of the archetypical architect’s detailed plans and models, carefully calibrated to produce a road map to a finished structure, Woods’ drawings are whimsical and thought-provoking, with radical new ideas being the intended result of his efforts. “No project is fully designed,” she said. “This is intentional — Woods allows the viewer to complete the project in his or her mind.”

Woods’ ideas started in his sketchbooks, which he crammed with detailed drawings. “He was extremely gifted with the pen,” said Becker, adding that many of the pieces are notated in a strange hybrid language that could be part Latin, part invented. The curators likened it to a kind of code that connected the conceptual fragments that run through Woods’ highly theoretical work.

“It could mean something, it could be that he’s creating almost these fictional artifacts of these supporting elements to engage with the larger drawings that he would do later,” Becker said. “They’re almost Da Vinci-like in their illegibility.”

Other questions remain about just what, exactly, Woods was up to with when he took pencil to paper. Take, for instance, a piece called Aero-Livinglab, from his Centricity series from the late 1980s, in which the architect was “essentially creating a utopian city” with “its own set of rules,” according to Becker. The drawing depicts a floating room that resembles an insect as much as it does some sort of alien zeppelin. Just what would the purpose of such a construction be?

“It could be an inhabitable space,” Becker said. “It could be small, it could be large. Often these things don’t have clear scale, but we do know that the point of Centricity was to invite a question of ‘what if?’”

An obituary on the Architectural Record website dubbed Woods “the last of the great paper architects” and said he “achieved cult-idol status among architects for his post-apocalyptic landscapes of dense lines and plunging perspectives. Deconstructivist in the most literal of ways, they were never formalist exercises. Instead, they conveyed the architect’s deep reservations as to the nature of contemporary society, and particularly its penchant for violence. He eschewed practice, claiming an interest in architectural ideas rather than the quotidian challenges of commercial building.”

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: barrachunkywordpress

Lebbeus Woods (1940 – 2012) fue un arquitecto conocido internacionalmente sobre todo por sus expresivos dibujos, con los que generó una poética particular de aires neorrománticos y cuya veta continuaron muchos estudios de los denominados deconstructivistas como Coop Himmelblau o la propia Zaha Hadid.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: rublouinartinfo

Тридцатого октября 2012 года архитектор Леббеус Вудс скончался в своей нью-йоркской квартире в возрасте семидесяти двух лет. Утром, в день его смерти, случившейся во время разрушительного урагана, эта новость осторожно просочилась в твиттер. Те, кому было знакомо это имя — архитекторы, критики, студенты и другие люди, восхищавшиеся его творческим видением, были опечалены; возможно, их больше поразил тот факт, что такой выдающийся голос замолчал столь внезапно. В хвалебных отзывах, появившихся в большом количестве после его смерти, о Вудсе писали как об архитекторе для архитекторов. Люди, знавшие его хоть немного лично, оставили проникновенные свидетельства о его оригинальном мышлении. Его считали почти священной фигурой, чью неподкупность в этой области поддерживало ее двойственную идентичность: как формы искусства и коммерчески успешного предприятия. Благодаря чему Вудс получил статус уникальной фигуры?

Строительство единного реализованного здания архитектора – «Павильон света» (удачное сочетание искусства и архитектуры), было завершено в китайском Ченгду лишь в этом году. Вудс получил известность за свой огромный вклад в архитектурный рисунок: его концептуальные планы с их резкими рваными линиями зданий и архитектурных ландшафтов, соединенных между собой простыми стальными конструкциями, попирающими законы гравитации, считаются одним из самых радикальных работ в экспериментальной архитектуре 1980-х и 1990-х годов. Известные архитекторы, такие, как Стивен Холл и Заха Хадид, и бесчисленные бывшие студенты Вудса (он преподавал в колледже «Купер Юнион» в Нью-Йорке и Европейской школе в Саас-Фи, Швейцария), выразили свое восхищение и признательность этим двухмерным архитектурным планировкам.

И все же, влияние его творчества распространяется не только на его активно проектирующих и строящих современников и учеников. Из-за своего небольшого портфолио Вудс незаслуженно оказался в стороне от широкого дискурса. Однако считать Вудса просто источником вдохновения для других, учителем и помощником, было бы одновременно уважительным и редукционистским объяснением. Принимая во внимание исключительную нематериальность его творчества, важно оценить, как те, что не знали архитектора лично, те, кто лично не извлек пользу из его научного руководства, могут осмыслить его наследие. Почему Леббеус Вудс был одним из самых признанных архитекторов своего времени?

Единственный раз я общался с Вудсом – это была непродолжительная переписка по электронной почте –прошлым летом. Тогда я искал архитектора, чтобы взять у него интервью, однако не учел того, что Вудс был уже болен. Он любезно поблагодарил меня за то, что я проявил к нему интерес, и предложил перенести это интервью на конец года (и я сделал это за несколько дней до его кончины). С работами Вудса я впервые столкнулся только три года назад. Я увидел проекцию одного из его эскизов на стене лофта в районе Трайбека во время демонстрации слайд-шоу для благотворительного аукциона.

В тот же вечер меня поразило мастерство Вудса, с которым он выполняет свои эскизы, и при этом почти не уделяет внимания деталям своего призрачного образа. С тех пор у меня сложилось новое представление о его нереализованных фантазиях. Находясь в стороне от практической деятельности, Вудс как будто бы постигал архитектуру вместо того, чтобы размышлять о том, как ее создавать. Я считаю, что эскизы Вудса по своей силе вполне могут сравниться с самыми крупными осуществленными проектами. Влияние его идей усиливается тем, что архитектор очень редко занимался строительством.

Вскоре после смерти Вудса архитектурный критик Дуглас Мерфи написал небольшой панегирик, в котором раскрывается значение этого архитектора в новейшей истории. «Откройте книгу по экспериментальной архитектуре того периода [конца 1980-х годов], где проникновенные и запоминающиеся эскизы Вудса…находятся рядом с работами таких архитекторов, как Даниэль Либескинд и Заха Хадид». Мерфи допускает довольно очевидное эстетическое сравнение. Если бы замыслы Вудса, выполненные им в виде эскизов или моделей, осуществились на практике, то они были бы очень похожи на те выразительные проекты, благодаря которым Либескинд и Хадид достигли вершин международной славы.

Но вместе с тем Мерфи выделяет Вудса и приводит доводы о том, что он отличается от «того поколения, которое в результате карьерного роста превратилось из авангардистских выскочек в звезд мировой величины». Опасаясь такой неизбежной перемены, начавшейся в 1980-х годах, Вудс провозгласил идею, что влияние архитектуры и ее способность к содержательному воздействию на среду заметно уменьшились.

Занятая огромным потреблением времени и ресурсов, среда вынуждена была отказаться от той роли архитектуры, где она формирует человеческое познание, а вместо этого заставить архитектуру участвовать в безудержном накоплении капитала. В какой-то мере, почти полный отказ от строительства был в своем роде, осмыслением этой превалирующей тендеции и личной позицией архитектора.

Вудс давал волю своим чувствам в cвоем удивительно проникновенных заметках, опубликованных в его блоге. Размышляя о проекте Олимпийского центра для водных видов спорта в Лондоне, он написал в феврале:

«Я чувствую себя брошенным и одиноким, потому что один [из] самых одаренных архитекторов моего времени опустился до простого решения функциональных задач в чисто экспрессионистских формах, не давая единственному лучу своего гения осветить подлинную человеческую сущность». В своих упреках Вудс выражает разочарование своим «безнадежно больным» другом: «Советовалась ли она со мной по поводу того, каким образом форма спорткомплекса должна выражать “геометрию воды в движении?” Нет. Если бы она спросила меня, то я порекомендовал бы ей отказаться от этой идеи, так как она слишком проста и банальна. Даже если бы это было бы достижимо в архитектурных формах (чего здесь не получилось, потому что текучесть воды не имеет ни формы, ни границ), это было бы гораздо привлекательнее, и отражало бы подлинный характер их отношений».

Критическое отношение Вудса к своим современникам говорит нам о его теоретических расхождених с ними. Сравним его эскизы с современными им разработками Хадид, Либескинда и других проектировщиков, которые увлекаются экспрессионизмом, созданным на компьютере. Сразу можно отметить то, что представления Вудса не предполагают точного переложения на строительные конструкции. Его структуры нависают и парят над городским пространством, вторгаются в уже существующие здания, зачем-то цепляются за их фасады и предлагают такие сложные конструктивные решения, которые выходят за рамки нашего понимания.

Кроме того, располагая бесконечным числом листов бумаги и полной свободой действия, Вудс всегда стремился изобразить неустойчивые «мимолетные» антиутопии и никогда не предлагал утопических решений. Его эскизы не дают представления о внутреннем пространстве и не имеют поперечных сечений. В противном случае они бы не вписались в концепцию Вудса об обманчивом подобии стабильности в этом мире. Его эпатажные проекты пронизаны духом того, что расколы, ереси и противоречия в истории человечества могут рассказать о новых способах строительства.

Для своего времени Вудс, конечно, парадоксальная фигура. Можно сказать, что он больше похож на итальянского архитектора XVIII века Джованни Батисту Пиранези, чем на кого-то из своих современников. Этих двух людей, живших в разные столетия, объединяет то, что они были «бумажными» архитекторами, замечательными чертежниками, которые тщательно вырисовывали каждый свой проект, при этом к строительству приняли только один из них. Часто отмечают удивительное сходство биографий этих архитекторов, однако о его значении говорится очень мало.

Как и Пиранези, Вудс понимал, что самые прогрессивные идеи архитектуры часто сдерживаются границами ее материальности. Гравюры Пиранези с видами древнего Рима бросили вызов догмам классицизма. Антиутопические проекты Вудса показали угодливый ответ архитектуры на коммерциализацию, ее готовность к возведению показных фасадов, чтобы сохранить нарушенный порядок вещей.

Вместо того, чтобы сразу же обратиться к решению этих давно назревших проблем путем организации строительства, Вудс, как и Пиранези, работал с другим материалом: он использовал не камень, не сталь, не пространство, а исключительно личное восприятие. Сумеречные пейзажи Вудса, как и римские фантазии Пиранези, почти без всякого посредничества позволяют оценить форму своего мира. Они бросают вызов существующим представлениям, но при этом не навязывая новые. Они вызывают всплеск эмоций, помогая обрести внутреннюю свободу. Они пробуждают новые возможности. Так же, как и величайшие здания в истории, архитектурные рисунки Вудса заставляют нас задуматься об условиях существования нашей собственной действительности.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: frwikipediaorg

Lebbeus Woods né en 1940 à Lansing dans le Michigan et mort le 30 octobre 2012 à New York, est un architecte américain.

Lebbeus Woods a étudié l’architecture à l’université de l’Illinois à Urbana-Champaign et le génie civil à l’université Purdue. Il a commencé par travailler pour Eero Saarinen avant de se consacrer en 1976 à la théorie et aux projets expérimentaux. Il a conçu des bâtiments à Chengdu en Chine et à La Havane à Cuba.

En 1994, il est lauréat du Chrysler Design Award. En 1998, Woods a co-fondé le Research Institute for Experimental Architecture, une institution à but non lucratif dédiée à faire progresser l’architecture expérimentale tout en valorisant l’architecture.

Jusqu’à sa mort, il enseignait l’architecture à la Cooper Union à New York et à European Graduate School à Saas-Fee dans le Valais.