LEBBEUS WOODS

ЛЕББЕУС ВУДС

レベウス・ウッズ

Firmament

source: thomforsyth

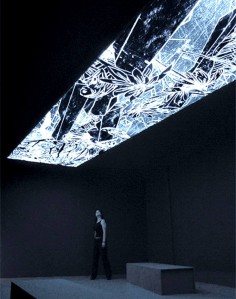

Light art and art lighting are fully incorporated in a gallery installation with architect Lebbeus Woods and artist Kiki Smith. At the heart of the show is a swath of radiant overhead imagery that provides the room’s only illumination. The piece’s integrated lighting creates a subtle luminous dark blue object that appears to float in space, while providing enough lighting to assist viewer navigation. Adjoining rooms feature the same low-level blue glow and art works highlighted with “moonlight.”

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: lebbeuswoods

Flashed around the world in September 2001, the pictures of the World Trade Center towers lying in ruins were both horrifying and—though few would openly admit it—strangely stimulating. The former because we instantly realized, with despair, that many people had died in the towers’ collapse, and that many others would suffer as a result of it for the rest of their lives. The latter because such a grand scale of destruction evoked an essential truth about human existence, a truth so disturbing that it is usually cloaked in denial: we are all going to die.

Not only will we die, but so will all our works. The great buildings, the great works of art, the great books, the great ideas, on which so many have spent the genius of human invention, will all fall to ruins and disappear in time. And not only will all traces of the human as we know it vanish, but the human itself will, too, as it continues an evolutionary trajectory accelerated by bioengineering and future technological advances. What all of this means is that we cannot take comfort in any form of earthly immortality that might mitigate the suffering caused by the certainty of our personal extinction.

It is true that through works of art, artists can live on in the thoughts and actions of others. This, however, is more of a comfort to the living than to the dead, and while it may help a living artist maintain a denial of death effective enough to keep believing that working and striving is somehow lasting, it is an illusion, and a pretty thin one at that. In contrast, the solidarity that develops between people who accept the inevitability of oblivion is more substantial and sustainable. When we witness an accident or disaster, we are drawn to it not because of ‘prurient interest,’ or an attraction to the pornography of violence, but rather to an event that strips away the illusions of denial and reveals the common denominator of the human condition. For the moment of our witnessing we feel, however uncomfortably, part of a much larger scheme of things, closer to what is true about our existence than we allow ourselves to feel in the normal course of living.

Religions have promised immortality and certainty in afterlives of various kinds, but for many today this is an inadequate antidote to despair. There are people who want to focus on the present and in it to feel a sense of exultation in being alive here and now, not in a postponed ‘later.’ This desire cuts across all class, race, gender, political and economic lines. In some religious lore, the ruins of human forms will be restored to their original states, protected and enhanced by the omniscient, enduring power of a divine entity. But for those who feel this is too late, the postponement of a full existence is less than ideal. For them, the present—always both decaying and coming into being, certain only in its uncertainty, perfect only in its imperfection—must be a kind of existential ideal. The ruins of something once useful or beautiful or symbolic of human achievement, speaks of the cycles of growth and decay that animate our lives and give them particular meaning relative to time and place. This is the way existence goes, and therefore we must find our exultation in confronting its ambiguity, even its confusion of losses and gains.

The role of art in all this has varied historically and is very much open to question from the viewpoint of the present. The painting and poetry of the Romantic era made extensive use of ruins to symbolize what was called The Sublime, a kind of exalted state of knowing and experience very similar to religious transcendence, lacking only the trappings of the church and overt references to God. Hovering close to religion, Romantic ruins were old, even ancient, venerable. They were cleansed of the sudden violence or slow decay that created them. There was something Edenic about them—Piranesi’s Rome, Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey,” Friedrich’s “Wreck of the Hope.” The best of such works are unsentimental but highly idealized, located intellectually and emotionally between the programmed horror of Medieval charnel houses and the affected nostalgia for a lost innocence of much architecture and painting of the late nineteenth century.

Taken together, these earlier conceptions are a long way from the fresh ruins of the fallen Twin Towers, the wreckage of Sarajevo, the blasted towns of Iraq, which are still bleeding, open wounds in our personal and collective psyches. Having witnessed these wounds—and in a palpable sense having received them—gives us no comfortable distance in which to rest and reflect on their meaning in a detached way. Hence, works of art that in some way allude to or employ these contemporary ruins cannot rely on mere depictions or representations—today that is the sober role of journalism, which must report what has happened without interpretation, aesthetic or otherwise. Rather it is for art to interpret, from highly personal points of view, what has happened and is still happening. In the narrow time-frame of the present, with its extremes of urgency and uncertainty, art can only do this by forms of direct engagement with the events and sites of conflict. In doing so, it gives up all claims to objectivity and neutrality. It gets involved. By getting involved, it becomes entangled in the events and contributes—for good and ill—to their shaping.

Thinking of Goya, Dix, Köllwitz, and so many others who bore witness and gave immediacy to conflict and the ruins of its aftermath, we realize that today the situation is very different. Because of instantaneous, world-wide reportage through electronic media, there no longer exists a space of time between the ruining of places, towns, cities, peoples, cultures and our affective awareness of them. Artists who address these situations are obliged to work almost simultaneously with them. Those ambitious to make masterpieces for posterity would do well to stay away, as no one of sensibility has the stomach for merely aestheticizing today’s tragic ruins. Imagine calling in Piranesi to make a series of etchings of the ruins of the Twin Towers. They would probably be powerful and original, but only for a future generation caring more for the artist’s intellectual and aesthetic mastery of his medium than for the immediacy of his work’s insights and interpretations. Contemporary artists cannot assume a safe aesthetic distance from the ruins of the present, or, if they do, they risk becoming exploitative.

How might the ruins of today, still fresh with human suffering, be misused by artists? The main way is using them for making money. This is a tough one, because artists live by the sale of their works. Even if a work of art addressing ruins is self-commissioned and donated, some money still comes as a result of publicity, book sales, lectures, teaching offers and the like. Authors of such works are morally tainted from the start. All they can do is admit that fact and hope that the damage they do is outweighed by some good. It is a very tricky position to occupy, and I would imagine that no artists today could or should make a career out of ruins and the human tragedies to which they testify.

Adorno stated that there can be no poetry after Auschwitz. His argument rested on the fact that the Holocaust could not be dealt with by the formal means of poetry, owing to poetry’s limits in dealing with extremes of reality. Judging by the dearth of poetry about the Holocaust, we are inclined to believe he was right. Looking at a similar dearth of painting, sculpture and architecture that engage more contemporary holocausts, we are inclined to extend his judgement into the present. Still, if we concede the impotence of plastic art in interpreting horrific events so close to the core of modern existence, we in effect say goodbye to them as vital instruments of human understanding. If we concede that, because of their immediacy, film and theater have been more effective, then we consign them to the limits of their own traditions. And so, we must ask, how have the arts dealt with the ruins of Sarajevo and Srebrenica, of Rwanda and Beirut and Iraq, of the Twin Towers’ site? How will they deal with the new ruins to come? Time itself has collapsed. The need is urgent. Can art help us here in the white heat of human struggle for the human, or must we surrender our hope for comprehension to the political and commercial interests that have never trusted art?

Today’s ruins challenge artists to redefine both their roles and their arts. People need works of art to mediate between themselves and the often incomprehensible conditions they live with, especially those resulting from catastrophic human violence. While not all works of art are universal, they share a universal quality, namely, the need to be perceived as the authentic expression of the artists’ experience. Without the perception of authenticity and the trust it inspires, art becomes rhetorical, commercial, and, by omission, destructive. What are the authentic forms of interpreting ruins—the death of the human, indeed, ultimately, of everything— today?

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: sfmomaorg

Architect Lebbeus Woods (1940-2012) dedicated his career to probing architecture’s potential to transform the individual and the collective. His visionary drawings depict places of free thought, sometimes in identifiable locations destroyed by war or natural disaster, but often in future cities. Woods, who sadly passed away last year as planning for this exhibition was under way, had an enormous influence on the field of architecture over the past three decades, and yet the built structures to his name are few. The extensive drawings and models on view present an original perspective on the built environment — one that holds high regard for humanity’s ability to resist, respond, and create in adverse conditions. “Maybe I can show what could happen if we lived by a different set of rules,” he once said.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: wired

He envisioned underground cities, floating buildings and an eternal space tomb for Albert Einstein worthy of the great physicist’s expansive intellect. With such grand designs, perhaps it’s not too surprising that the late Lebbeus Woods, one of the most influential conceptual architects ever to walk the earth, had only one of his wildly imaginative designs become a permanent structure.

Instead of working with construction and engineering firms, Woods dreamed up provocative creations that weren’t bound by the rules of society or even nature, according to Joseph Becker and Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, co-curators of a new exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art titled Lebbeus Woods, Architect.

“It was almost a badge of honor to never have anything built, because you were not a victim of the client,” Becker told Wired during a preview of the fascinating show, which opens Saturday and runs through June 2. While not a full retrospective of Woods’ career, the exhibit shows off three decades of his work in the form of drawings, paintings, models and sketchbooks filled with bold ideas, raw concepts and cryptic inscriptions. (See several examples of Woods’ work in the gallery above.)

As the curators discussed Woods’ work and his impact on the world of architecture, they talked of a brilliant mind consumed with disruption, with confronting the boring, repetitive spaces humans have become accustomed to living in by challenging the “omnipresence of the Cartesian grid.” Woods’ fantastic visions included buildings designed for seismic hot zones that might move in response to earthquakes, or a sprawling city that would exist underneath a divided Berlin, providing a sort of subterranean salon where individuals from the East and West might mingle, free from the conflicting ideologies of their governments.

“He was very focused, I think, in all of his work, in what he said was ‘architecture for its own sake,’” Becker said. “Not architecture for clients, not architecture that is diluted, and not architecture that really had to be held up against certain primary factors, including gravity or government.”

Woods found his place in the conceptual architecture movement that sprang from the 1960s and ’70s, when firms like Superstudio and Archigram presented a radical peek into a possible — if improbable — future. Casting a skeptical eye on the way humans lived in cities, these conceptual architects were more interested in raising questions than in crafting blueprints for buildings that would actually be built of concrete, steel and glass.

In fact, only one of the nearly 200 fascinating drawings and other works on display in Lebbeus Woods, Architect was ever meant to be built, said Dunlop Fletcher. Instead of the archetypical architect’s detailed plans and models, carefully calibrated to produce a road map to a finished structure, Woods’ drawings are whimsical and thought-provoking, with radical new ideas being the intended result of his efforts. “No project is fully designed,” she said. “This is intentional — Woods allows the viewer to complete the project in his or her mind.”

Woods’ ideas started in his sketchbooks, which he crammed with detailed drawings. “He was extremely gifted with the pen,” said Becker, adding that many of the pieces are notated in a strange hybrid language that could be part Latin, part invented. The curators likened it to a kind of code that connected the conceptual fragments that run through Woods’ highly theoretical work.

“It could mean something, it could be that he’s creating almost these fictional artifacts of these supporting elements to engage with the larger drawings that he would do later,” Becker said. “They’re almost Da Vinci-like in their illegibility.”

Other questions remain about just what, exactly, Woods was up to with when he took pencil to paper. Take, for instance, a piece called Aero-Livinglab, from his Centricity series from the late 1980s, in which the architect was “essentially creating a utopian city” with “its own set of rules,” according to Becker. The drawing depicts a floating room that resembles an insect as much as it does some sort of alien zeppelin. Just what would the purpose of such a construction be?

“It could be an inhabitable space,” Becker said. “It could be small, it could be large. Often these things don’t have clear scale, but we do know that the point of Centricity was to invite a question of ‘what if?’”

An obituary on the Architectural Record website dubbed Woods “the last of the great paper architects” and said he “achieved cult-idol status among architects for his post-apocalyptic landscapes of dense lines and plunging perspectives. Deconstructivist in the most literal of ways, they were never formalist exercises. Instead, they conveyed the architect’s deep reservations as to the nature of contemporary society, and particularly its penchant for violence. He eschewed practice, claiming an interest in architectural ideas rather than the quotidian challenges of commercial building.”

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: barrachunkywordpress

Lebbeus Woods (1940 – 2012) fue un arquitecto conocido internacionalmente sobre todo por sus expresivos dibujos, con los que generó una poética particular de aires neorrománticos y cuya veta continuaron muchos estudios de los denominados deconstructivistas como Coop Himmelblau o la propia Zaha Hadid.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: rublouinartinfo

Тридцатого октября 2012 года архитектор Леббеус Вудс скончался в своей нью-йоркской квартире в возрасте семидесяти двух лет. Утром, в день его смерти, случившейся во время разрушительного урагана, эта новость осторожно просочилась в твиттер. Те, кому было знакомо это имя — архитекторы, критики, студенты и другие люди, восхищавшиеся его творческим видением, были опечалены; возможно, их больше поразил тот факт, что такой выдающийся голос замолчал столь внезапно. В хвалебных отзывах, появившихся в большом количестве после его смерти, о Вудсе писали как об архитекторе для архитекторов. Люди, знавшие его хоть немного лично, оставили проникновенные свидетельства о его оригинальном мышлении. Его считали почти священной фигурой, чью неподкупность в этой области поддерживало ее двойственную идентичность: как формы искусства и коммерчески успешного предприятия. Благодаря чему Вудс получил статус уникальной фигуры?

Строительство единного реализованного здания архитектора – «Павильон света» (удачное сочетание искусства и архитектуры), было завершено в китайском Ченгду лишь в этом году. Вудс получил известность за свой огромный вклад в архитектурный рисунок: его концептуальные планы с их резкими рваными линиями зданий и архитектурных ландшафтов, соединенных между собой простыми стальными конструкциями, попирающими законы гравитации, считаются одним из самых радикальных работ в экспериментальной архитектуре 1980-х и 1990-х годов. Известные архитекторы, такие, как Стивен Холл и Заха Хадид, и бесчисленные бывшие студенты Вудса (он преподавал в колледже «Купер Юнион» в Нью-Йорке и Европейской школе в Саас-Фи, Швейцария), выразили свое восхищение и признательность этим двухмерным архитектурным планировкам.

И все же, влияние его творчества распространяется не только на его активно проектирующих и строящих современников и учеников. Из-за своего небольшого портфолио Вудс незаслуженно оказался в стороне от широкого дискурса. Однако считать Вудса просто источником вдохновения для других, учителем и помощником, было бы одновременно уважительным и редукционистским объяснением. Принимая во внимание исключительную нематериальность его творчества, важно оценить, как те, что не знали архитектора лично, те, кто лично не извлек пользу из его научного руководства, могут осмыслить его наследие. Почему Леббеус Вудс был одним из самых признанных архитекторов своего времени?

Единственный раз я общался с Вудсом – это была непродолжительная переписка по электронной почте –прошлым летом. Тогда я искал архитектора, чтобы взять у него интервью, однако не учел того, что Вудс был уже болен. Он любезно поблагодарил меня за то, что я проявил к нему интерес, и предложил перенести это интервью на конец года (и я сделал это за несколько дней до его кончины). С работами Вудса я впервые столкнулся только три года назад. Я увидел проекцию одного из его эскизов на стене лофта в районе Трайбека во время демонстрации слайд-шоу для благотворительного аукциона.

В тот же вечер меня поразило мастерство Вудса, с которым он выполняет свои эскизы, и при этом почти не уделяет внимания деталям своего призрачного образа. С тех пор у меня сложилось новое представление о его нереализованных фантазиях. Находясь в стороне от практической деятельности, Вудс как будто бы постигал архитектуру вместо того, чтобы размышлять о том, как ее создавать. Я считаю, что эскизы Вудса по своей силе вполне могут сравниться с самыми крупными осуществленными проектами. Влияние его идей усиливается тем, что архитектор очень редко занимался строительством.

Вскоре после смерти Вудса архитектурный критик Дуглас Мерфи написал небольшой панегирик, в котором раскрывается значение этого архитектора в новейшей истории. «Откройте книгу по экспериментальной архитектуре того периода [конца 1980-х годов], где проникновенные и запоминающиеся эскизы Вудса…находятся рядом с работами таких архитекторов, как Даниэль Либескинд и Заха Хадид». Мерфи допускает довольно очевидное эстетическое сравнение. Если бы замыслы Вудса, выполненные им в виде эскизов или моделей, осуществились на практике, то они были бы очень похожи на те выразительные проекты, благодаря которым Либескинд и Хадид достигли вершин международной славы.

Но вместе с тем Мерфи выделяет Вудса и приводит доводы о том, что он отличается от «того поколения, которое в результате карьерного роста превратилось из авангардистских выскочек в звезд мировой величины». Опасаясь такой неизбежной перемены, начавшейся в 1980-х годах, Вудс провозгласил идею, что влияние архитектуры и ее способность к содержательному воздействию на среду заметно уменьшились.

Занятая огромным потреблением времени и ресурсов, среда вынуждена была отказаться от той роли архитектуры, где она формирует человеческое познание, а вместо этого заставить архитектуру участвовать в безудержном накоплении капитала. В какой-то мере, почти полный отказ от строительства был в своем роде, осмыслением этой превалирующей тендеции и личной позицией архитектора.

Вудс давал волю своим чувствам в cвоем удивительно проникновенных заметках, опубликованных в его блоге. Размышляя о проекте Олимпийского центра для водных видов спорта в Лондоне, он написал в феврале:

«Я чувствую себя брошенным и одиноким, потому что один [из] самых одаренных архитекторов моего времени опустился до простого решения функциональных задач в чисто экспрессионистских формах, не давая единственному лучу своего гения осветить подлинную человеческую сущность». В своих упреках Вудс выражает разочарование своим «безнадежно больным» другом: «Советовалась ли она со мной по поводу того, каким образом форма спорткомплекса должна выражать “геометрию воды в движении?” Нет. Если бы она спросила меня, то я порекомендовал бы ей отказаться от этой идеи, так как она слишком проста и банальна. Даже если бы это было бы достижимо в архитектурных формах (чего здесь не получилось, потому что текучесть воды не имеет ни формы, ни границ), это было бы гораздо привлекательнее, и отражало бы подлинный характер их отношений».

Критическое отношение Вудса к своим современникам говорит нам о его теоретических расхождених с ними. Сравним его эскизы с современными им разработками Хадид, Либескинда и других проектировщиков, которые увлекаются экспрессионизмом, созданным на компьютере. Сразу можно отметить то, что представления Вудса не предполагают точного переложения на строительные конструкции. Его структуры нависают и парят над городским пространством, вторгаются в уже существующие здания, зачем-то цепляются за их фасады и предлагают такие сложные конструктивные решения, которые выходят за рамки нашего понимания.

Кроме того, располагая бесконечным числом листов бумаги и полной свободой действия, Вудс всегда стремился изобразить неустойчивые «мимолетные» антиутопии и никогда не предлагал утопических решений. Его эскизы не дают представления о внутреннем пространстве и не имеют поперечных сечений. В противном случае они бы не вписались в концепцию Вудса об обманчивом подобии стабильности в этом мире. Его эпатажные проекты пронизаны духом того, что расколы, ереси и противоречия в истории человечества могут рассказать о новых способах строительства.

Для своего времени Вудс, конечно, парадоксальная фигура. Можно сказать, что он больше похож на итальянского архитектора XVIII века Джованни Батисту Пиранези, чем на кого-то из своих современников. Этих двух людей, живших в разные столетия, объединяет то, что они были «бумажными» архитекторами, замечательными чертежниками, которые тщательно вырисовывали каждый свой проект, при этом к строительству приняли только один из них. Часто отмечают удивительное сходство биографий этих архитекторов, однако о его значении говорится очень мало.

Как и Пиранези, Вудс понимал, что самые прогрессивные идеи архитектуры часто сдерживаются границами ее материальности. Гравюры Пиранези с видами древнего Рима бросили вызов догмам классицизма. Антиутопические проекты Вудса показали угодливый ответ архитектуры на коммерциализацию, ее готовность к возведению показных фасадов, чтобы сохранить нарушенный порядок вещей.

Вместо того, чтобы сразу же обратиться к решению этих давно назревших проблем путем организации строительства, Вудс, как и Пиранези, работал с другим материалом: он использовал не камень, не сталь, не пространство, а исключительно личное восприятие. Сумеречные пейзажи Вудса, как и римские фантазии Пиранези, почти без всякого посредничества позволяют оценить форму своего мира. Они бросают вызов существующим представлениям, но при этом не навязывая новые. Они вызывают всплеск эмоций, помогая обрести внутреннюю свободу. Они пробуждают новые возможности. Так же, как и величайшие здания в истории, архитектурные рисунки Вудса заставляют нас задуматься об условиях существования нашей собственной действительности.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: frwikipediaorg

Lebbeus Woods né en 1940 à Lansing dans le Michigan et mort le 30 octobre 2012 à New York, est un architecte américain.

Lebbeus Woods a étudié l’architecture à l’université de l’Illinois à Urbana-Champaign et le génie civil à l’université Purdue. Il a commencé par travailler pour Eero Saarinen avant de se consacrer en 1976 à la théorie et aux projets expérimentaux. Il a conçu des bâtiments à Chengdu en Chine et à La Havane à Cuba.

En 1994, il est lauréat du Chrysler Design Award. En 1998, Woods a co-fondé le Research Institute for Experimental Architecture, une institution à but non lucratif dédiée à faire progresser l’architecture expérimentale tout en valorisant l’architecture.

Jusqu’à sa mort, il enseignait l’architecture à la Cooper Union à New York et à European Graduate School à Saas-Fee dans le Valais.