ROBERT WILSON

بوب ويلسون

鲍伯·威尔逊

בוב וילסון

ロバート·ウィルソン

밥 윌슨

БОБ УИЛСОН

Odyssey (Οδύσσεια)

source: n-tgr

Το μεγάλο έπος της αρχαίας ελληνικής γραμματείας παρακολουθεί το ταξίδι της επιστροφής του Οδυσσέα στην πατρίδα μετά τον Τρωικό πόλεμο, αλλά και όσα συμβαίνουν όταν ο ήρωας φτάσει στην Ιθάκη. Πρόκειται για ένα υπερβατικό “παραμύθι”, που υπήρξε πάντα και θα συνεχίσει να αποτελεί το κατεξοχήςν συμβολικό κείμενο για την ανθρώπινη περιπέτεια και την περιπλάνηση της ύπαρξης σε έναν τραχύ αλλά συναρπαστικό κόσμο.

Η συνάντηση του Ρόμπερτ Ουίλσον με τον ομηρικό κόσμο είναι ένα από τα μεγάλα καλλιτεχνικά γεγονότα της φετινής περιόδου. Ένας από τους πιο σημαντικούς και καταξιωμένους δημιουργούς του παγκόσμιου θεάτρου προσεγγίζει με τον δικό του, μοναδικό τρόπο το υλικό του Ομήρου. Η ευαισθησία, η ευρηματικότητα και η φαντασία του μεγάλου αμερικανού δημιουργού συντονίζονται με το ομηρικό πνεύμα και οδηγούν σε μια ιδιαίτερη θεατρική γλώσσα, που μαγεύει τις αισθήσεις του θεατή. 18 αυστηρά επιλεγμένοι ερμηνευτές και οι σταθεροί, διεθνούς φήμης, συνεργάτες του Ουίλσον υλοποιούν με υψηλή αισθητική το ξεχωριστό αυτό εγχείρημα, που απευθύνεται σε όλους τους θεατές, ανεξάρτητα από την ηλικία ή τη θεατρική τους προπαιδεία.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: minglewitharts

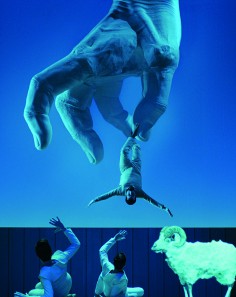

Ο Robert Wilson είναι ένας πραγματικός μάγος που κατόρθωσε να στήσει μια παράσταση υπερθέαμα… μια παράσταση εμβληματική μέσα στην απλότητά της. Η Οδύσσεια – Μια παράσταση του Robert Wilson, βασισμένη στο έπος του Ομήρου υπό τη σκηνοθετική του ματιά γίνεται ένα παραμύθι για μικρούς και μεγάλους… μας διηγείται μια ιστορία επική αλλά πέρα για πέρα ανθρώπινη… παρουσιάζει έναν Οδυσσέα στις πραγματικές τους διαστάσεις που ο καθένας επιθυμεί να γνωρίσει και να ακούσει τις ιστορίες του. Πέρα από στερεότυπα και κλισέ η Οδύσσεια του Wilson είναι ένα τρίωρο ανατρεπτικό καρτούν επί σκηνής (μου θύμισε αρκετά το χιούμορ από το Les triplettes de Belleville και τη λυρικότητα του L’illusionniste). Η εικονοκλαστική του γλώσσα πλούσια, με αναφορές σε ποικίλες μορφές τέχνης από τις εξαϋλωμένες φιγούρες του El Greco και τους χαρακτήρες της κωμωδίας του William Shakespeare, Όνειρο καλοκαιρινής νυκτός, στο βουβό κινηματογράφο και την παντομίμα και από εκεί ως την πανκ κουλτούρα και τα σκίτσα του Enki Bilal.

Κάθε σκηνή στην Οδύσσεια του Wilson θα μπορούσε να είναι μια τεράστια μετόπη ενός αρχαϊκού ναού που εξιστορεί την ιστορία του πολυμήχανου ήρωα και το ταξίδι της επιστροφής στην Ιθάκη. Σκηνές στημένες με μια δωρικότητα αλλά τόσο ζωντανές και γεμάτες ενάργεια που κάνουν το θεατή να συμπάσχει στο δράμα του ήρωα. Οι ηθοποιοί καλυμμένοι με λευκή πούδρα και χρωματιστό μακιγιάζ, το οποίο τονίζει τα χαρακτηριστικά τους, θυμίζουν τόσο πολύ αρχαϊκά αγάλματα που κανείς μπορεί να θαυμάσει στο Μουσείο της Ακρόπολης. Άλλες φορές ο τρόπος που είναι στημένες οι σκηνές και οι ηθοποιοί μοιάζουν λες και έχουν ξεπηδήσει από κλασσικούς αμφορείς ενώ τα πρόσωπα των ηθοποιών παραπέμπουν στις νεκρικές μάσκες των μυκηναίων βασιλιάδων που υπάρχουν στο Εθνικό Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο Αθηνών.

Η σκηνή του Εθνικού Θεάτρου μετατρέπεται σε ένα τεράστιο μουσικό κουτί το οποίο καλούμαστε να ανοίξουμε…. Και η μουσική ξεκινά, ο Όμηρος – Νικήτας Τσακίρογλου αρχίζει να απαγγέλλει τους πρώτους στίχους του έπους του Οδυσσέα, τα φώτα αναβοσβήνουν εναλλάξ στη σκηνή, στην οροφή, στην πλατεία και η μαγεία ξεκινά… οι ηθοποιοί πιάνουν την άκρη του μύθου και ξετυλίγουν την ιστορία σε μια μαγεία εικόνων που μας μεταφέρουν στα βάθη του χρόνου…

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: n-tgr

The great epic work of ancient Greek poetry tells the story of Odysseus’s journey home after the Trojan War and what happens when the hero arrives at Ithaca. It is a transcendental tale that has always been the symbolic text par excellence about human adventure and the wanderings of existence in a harsh but exciting world.

Robert Wilson’s encounter with Homer is one of the major artistic events of this season. One of the most influential and acclaimed artists in world theatre brings his own unique approach to the material. The sensitivity, inventiveness and imagination of the great American director resonate with the Homeric spirit, creating a spellbinding new theatrical language. Eighteen carefully chosen performers and Wilson’s own internationally renowned collaborators bring all their artistry to bear on this unique venture, which is intended for all audiences, regardless of age or experience of the theatre.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: klpteatroit

“Bob, te lo confesso, me l’aspettavo pesante, ma mi hai illuminato l’anima di blu”.

“Da ragazzo mi trovavo in Grecia per la prima volta, quando qualcuno mi portò a vedere un’edizione teatrale dell’Odissea – racconta Robert Wilson – Davvero non ricordo quanto sia durata veramente, ma mi sembrò interminabile, pesantissima, seriosa. E ricordo di aver pensato: ma deve proprio essere così?”.

“Odyssey”, coproduzione Piccolo Teatro di Milano e Teatro Nazionale di Grecia, tiene fede a quella che è la risposta del regista: “Per me dovrebbe essere più lieve”.

Lievità, leggerezza, ironia, giocosità. L’opera è il tripudio di un perfetto lavoro d’ensemble che si manifesta agli occhi con assoluta semplicità e leggerezza, strappando sorrisi e risate con le sue trovate ironiche e destabilizzanti.

Come tradizione vuole, l’Odissea viene narrata. E quindi Omero, seduto sul bordo del proscenio, attende gli spettatori in sala. La voce del poeta ci conduce all’assemblea degli dei dell’Olimpo, “i mortali si imbattono in una tragedia dopo l’altra, non crescono, non imparano dai loro errori” proclama Zeus furente, ma Atena cerca di farsi sentire ponendo l’attenzione sul singolo e non sul genere umano. E il singolo altri non è che Odisseo, di cui Atena invoca la salvezza.

Un viaggio a tinte blu su una scena essenziale: lo spazio si contrae e si dilata modificandosi sotto gli occhi del pubblico. I toni dell’indaco e del cobalto si mescolano in quel colore tutto wilsoniano, trasognante e nostalgico, nei racconti di Odisseo; si modifica alla luce illuminandosi nell’azione quando la storia diviene presente. A far da contrasto, la furia del rosso campeggia nel regno dei morti, nelle azioni violente.

Lo spettacolo interagisce con la platea e coinvolge il pubblico nei suoi giochi di luce; le armi di vetro e specchi rifrangono i riflessi in ogni dove, le luci di sala e quelle di scena duettano prima del prologo in un concerto visivo di impatto notevole. Tutto è un felice connubio.

Le musiche di Thodoris Ekonomou, eseguite dal vivo dallo stesso compositore, aggiungono un plusvalore, accompagnando i personaggi principali con un tema musicale proprio e diventando esse stesse non colonna sonora ma intreccio drammaturgico.

Lo spettacolo è un susseguirsi di immagini evocative ed eleganti che potrebbero essere tutte narrate, ma chi scrive decide di non illustrarle perché “Odyssey”, come tutte le opere di Wilson, è uno spettacolo per gli occhi, e dallo sguardo deve esser direttamente contemplato. Come tutte le opere, si diceva, ma con una differenza fondamentale: l’Odissea raccontata così sorpassa lo stupore e soddisfa.

Soddisfa perché è un’opera bella, d’una bellezza neoclassica, ed epurata dal naturalismo tende all’ideale, alla perfezione delle proporzioni; nell’equilibrio delle proporzioni dell’universo wilsoniano non ci sono solo le forme, ma vi è spazio, luce, suono, tempo.

Il vivido immaginario wilsoniano mette tutti d’accordo. Il pubblico si diverte, riflette e si lascia trasportare da un’Odissea in greco moderno che si serve del gesto come medium principale, come un film muto.

La trascrizione di Simon Armitage rende contemporaneo il più antico dei poemi; l’adattamento è di Wolfang Wiens, drammaturgo tedesco deceduto nel maggio scorso, a cui l’opera è dedicata.

Qualcuno dice che il teatro non è per tutti, ma l’“Odyssey” è capace di incantare un pubblico variegato, scolaresche, curiosi, amatori, dando al teatro ciò che è gli è proprio: il confronto e la relazione.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: robertwilson

Of Wilson’s artistic career, Susan Sontag has added “it has the signature of a major artistic creation. I can’t think of any body of work as large or as influential.” A native of Waco, Texas, Wilson was educated at the University of Texas and arrived in New York in 1963 to attend Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute. Soon thereafter, Wilson set to work with his Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds and, together with his company, developed his first signature works including King of Spain (1969), Deafman Glance (1970), The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin (1973), and A Letter for Queen Victoria (1974). Regarded as a leader of Manhattan’s then-burgeoning downtown art scene, Wilson turned his attention to large-scale opera and, with Philip Glass, created the monumental Einstein on the Beach (1976), which achieved worldwide acclaim and altered conventional notions of a moribund form.

Following Einstein, Wilson worked increasingly with major European theaters and opera houses. In collaboration with internationally renowned writers and performers, Wilson created landmark original works that were featured regularly at the Festival d’Automne in Paris, Der Berliner Ensemble, the Schaubühne in Berlin, the Thalia Theater in Hamburg, the Salzburg Festival, and the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival. At the Schaubühne he created Death, Destruction & Detroit (1979) and Death, Destruction & Detroit II (1987); and at the Thalia he presented the groundbreaking musical works The Black Rider (1991) and Alice (1992). He has also applied his striking formal language to the operatic repertoire, including Parsifal in Hamburg (1991), Houston (1992), and Los Angeles (2005); The Magic Flute (1991) and Madame Butterfly (1993); and Lohengrin at the Metropolitan Opera in New York (1998 & 2006). Wilson recently completed an entirely new production, based on an epic poem from Indonesia, entitled I La Galigo, which toured extensively and appeared at the Lincoln Center Festival in the summer of 2005. Wilson continues to direct revivals of his most celebrated productions, including The Black Rider in London, San Francisco, Sydney, Australia, and Los Angeles; The Temptation of St. Anthony in New York and Barcelona; Erwartung in Berlin; Madama Butterfly at the Bolshoi Opera in Moscow; and Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen at Le Châtelet in Paris.

Wilson’s practice is firmly rooted in the fine arts and his drawings, furniture designs, and installations have been exhibited in museums and galleries internationally. Extensive retrospectives have been presented at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. He has mounted installations at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, London’s Clink Street Vaults, and the Guggenheim Museums in New York and Bilbao. His extraordinary tribute to Isamu Noguchi has been exhibited recently at the Seattle Art Museum, and his installations of the Guggenheim’s Giorgio Armani retrospective have traveled to London, Rome, and Tokyo.

Each summer Wilson decamps to the Watermill Center, a laboratory for the arts and humanities in eastern Long Island. The Watermill Center brings together students and experienced professionals in a multi-disciplinary environment dedicated to creative collaboration. A gala benefit and re-dedication of the reconstructed main building takes place every summer.

Wilson’s numerous awards and honors include an Obie award for direction, the Golden Lion for sculpture from the Venice Biennale, the 3rd Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize for Lifetime Achievement, the Premio Europa award from Taormina Arte, two Guggenheim Fellowship awards, the Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship award, a nomination for the Pulitzer Prize in Drama, the Golden Lion for Sculpture from the Venice Biennale, election to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the National Design Award for Lifetime Achievement. He has been named a “Commandeur des arts et des letters” by the French Minister of Culture.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: nadiadallevedove

Robert Wilson (Progetto, regia, scene e luci) voleva realizzare un’Odissea leggera. Che potesse anche farci sorridere.

Ha scelto la Compagnia del Teatro Nazionale Greco per innalzare un ponte tra il passato e il presente, tra la Grecia odierna e il resto del mondo, stravolgendo la visione di chi ha sempre visto e messo in scena quest’opera in maniera tradizionale.

Wilson ha riempito di vuoto l’Odissea, il viaggio dei viaggi.

Il vuoto commovente dei volti truccati di bianco, di quelle movenze dei corpi più vicini al teatro senza parola, di quel testo così scarno che s’inclina a ogni soffio di vento che arriva dagli incontri che Omero fa insieme ai suoi compagni di viaggio. Un vuoto che respiriamo dall’antichità a oggi, per ammettere che esiste una sola Odissea: quella che riporta ciascuno di noi nella propria Itaca.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: prelecturstanfordedu

Robert Wilson is an acclaimed director, stage designer, performer, writer, furniture designer, draftsman, and educator of international and multidisciplinary scope. A Texas-born American, he has to a large degree made his career in Europe. An artist of the stage, he has come to that profession by way of business school, architectural training, painting, and chance encounters with uniquely inspirational individuals. Perhaps because of this non-linear trajectory, he has again and again felt cause and had vision to test and question all of the presumed essential elements of the theater: the spectator, the performer, the writer, the stage, the story. His productions are lengthy yet highly controlled, minimalist yet intricately detailed. “I never studied theatre,” he admits. “If I had studied theatre, I would not be making the theatre I’m making.”

Born in Waco in 1941, Wilson was exposed to the performing arts as a child only in the most peripheral of manners, by way of a dance instructor whose teaching has since then manifested a steady presence, directly or indirectly, within his work:

[Byrd Hoffman] was a dancer — she was a ballet dancer — she was in her 70’s when I met her. She taught the dance — she understood the body in a remarkable way….[S]he talked to me about the energy in my body, about relaxing, letting energy flow through….She was amazing because she never taught a technique, she never gave me a way to approach it, it was more that I discovered it on my own.

The initial result of his interaction with Hoffman was, according to Wilson, the correction of his childhood speech impediment. But years later, when he was a young adult and had begun his career in earnest, he named the group with which he was creating and performing experimental theatrical works in New York the Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds. More than anything this seems to have been a tribute to the way in which Hoffman directed Wilson toward a knowledge of the body — or, better, a knowledge of the body’s own knowledge, innate and unconscious.

The challenge Wilson set for himself, then, was to create works that drew upon this bodily knowledge from both sides of the invisible boundary that divides the stage from the audience. An early, resonant example of Wilson’s approach was Deafman Glance (1970). Inspired in part by Wilson’s important friendship with a deaf boy named Raymond Andrews, whom he adopted as his son, the mostly silent work was constructed of fantastical scenes composed purely of performed images: this was not performance that resulted in images, but images that, essentially, called for performance. It was a feat of theater innovative enough to incite Louis Aragon, the Surrealist poet, to compose a fervent letter to his colleague André Breton:

The world of a deaf child opened up to us like a wordless mouth. For more than four hours, we went to inhabit this universe where, in the absence of words, of sounds, sixty people had no words except to move…I never saw anything more beautiful in the world since I was born. Never never has any play come anywhere near this one, because it is at once life awake and the life of closed eyes, the confusion between everyday life and the life of each night, reality mingle[d] with dream, all that’s inexplicable in the life of [a] deaf man.

Directing the stage toward the presentation of images, while avoiding the traditional notion of what constitutes “plot,” Wilson had undertaken what he describes as a formalist approach, one that has not faltered in the intervening years. “I prefer formalism in presenting a work because it creates more distance, more mental space,” he asserts. He has always believed that the more structurally, procedurally, emotionally, and visually controlled a theatrical situation is, the more “space” there is for real truth — not represented truth — to crystallize in the openness that remains. “Often I feel that what I’m seeing onstage is based on a lie,” he says about traditionally acted theater. “You know, an actor thinks he’s being natural but he’s not, he’s acting natural and that is something that is artificial. By being artificial, I think you can…know more about yourself, be closer to…a truth.”

Thus Wilson directs his performers’ movements down to the smallest minutiae (the way a wrist turns; the precise angle of the shoulders) and, very often, compels the performers to reduce their actions to a strikingly slow pace. The delivery of lines requires equal control; he instructs actors to speak in regulated monotones: not robotic, yet not dynamic. And Wilson’s attention to the intricacies of stage design is as intense as, or more intense than, his interactions with the performers. In fact, even as Wilson began to move beyond mostly silent works and into productions that included language (narrative or not), beginning with the linguistically deconstructive A Letter for Queen Victoria (1974) the visual design remained the foundational focus. In reference to his work for two actors I was sitting on my patio and this guy appeared I thought I was hallucinating (1977) Wilson describes the transition from writing to envisioning the production:

…I began making sketches, often on long rolls of paper (as well as in my notebook), of the image I was thinking of using for a basic stage set. I made about twenty-five drawings a day for two weeks, sometimes making slight alterations in them. I often follow a similar procedure before arriving at a final image used as a model for scenery.

His fervent interest in formal control — how each theatrical element fits together — extends to his personally designing the often-spare set pieces, which are most notably chairs thematically suited to the mood or character(s) of the theatrical pieces. Both his drawings and his chairs have been exhibited numerous times and are considered legitimate works of art in their own right by Wilson and critics alike.

Wilson also pays a great deal of attention — perhaps the most — to a more ineffable part of his productions: the lighting. This is not to say that he is formally trained as a lighting technician; indeed, as with so many of the elements of his works, including choreography, set construction, dramaturgy, and even directing, “Wilson” implies a collaborative effort. But it is he who, in painstaking planning sessions, determines exactly how light should define any given scene. Beverly Emmons, who has worked with Wilson on many projects, describes his method:

What Bob does with light which is extraordinary and difficult and unusual is to separate all the elements from each other and control them independently….He wants the floor treated as a whole unit and separately painted with light. He wants the background treated as another whole, with maybe one color shaded into another….Then he wants the human figure separately etched out with light, and very often he wants the head or even nose of that figure separately lighted.

And it is because he can create this particular sort of structured visual control that Wilson is — and has been to an increasing degree over the years — willing to include elements that are, as it were, outside of himself. The most well known early example is Einstein on the Beach (1976) the spectacularly reviewed, four-hour-long opera that he created with composer Philip Glass. The two chose their subject jointly — Albert Einstein becoming the mythic focus around which images of motion, space travel, and justice in the twentieth century circled — and then Wilson led the discussion regarding the visual structure. It was not until that dialogue had been mostly completed that Glass began to compose his minimalist, mathematically measured score. Glass remembers:

I put [Wilson’s notebook of sketches] on the piano and composed each section like a portrait of the drawing before me. The score was begun in the spring of 1975 and completed by the following November, and those drawings were before me all the time.

As his career moved forward, hitting bumps in funding and critical response, and always, for better or worse, achieving more acclaim in Europe than in America, Wilson began to diversify the works upon which he applied his formal structure. In the 1980s, while continuing to craft productions purely Wilsonian in character — the multinational, multi-site epic the CIVIL warS: a tree is best measured when it is down (1981-83); The Golden Windows (1982); a revival of Einstein on the Beach (1984); The Knee Plays (scenes that had been presented as “joints” between acts in the CIVIL wars; 1984) — he began to more regularly approach texts that he had had no part in writing. He produced Hamletmaschine (1986), in conjunction with its author, Heiner Müller. He staged Euripides’ famed tragedy Alcestis (1986), Shakespeare’s King Lear (1985), and Ibsen’s Peer Gynt (2005). And he continued to demonstrate a dedication to the theater’s intersection with music as well, not only in such collaborations as that with Tom Waits and William S. Burroughs in the musical The Black Rider: The Casting of the Magic Bullets (1990), but also in classic works of opera. In 1991 he produced both Mozart’s The Magic Flute at the Opéra Bastille in Paris and Wagner’s Lohengrin at the Opernhaus Zürich (the latter also at the Metropolitan Opera, New York, in 1998); he went on to stage the entire Ring Cycle, starting in 2000 at the Opernhaus Zürich.

A striking feature of all of these later works is the fact that, as Wilson refracts the original text or score through his unmistakable, structured aesthetic, the result again and again is a production that remains true to the artist’s earliest tenets. Hamlet: A Monologue, an adaptation first produced in 1995 and starring Wilson himself as the sole actor, is a focused example of this skillful mediation. In the midst of fifteen disjointed, disordered scenes, he maneuvers the iconic work, so well known to so many audiences, into an entity both discernible and utterly strange. By setting the play in his typically visually spare and location-less zone, stripped even of the directorial structure that Shakespeare had given it, Wilson allows the text to form open-ended meanings, freed from a singular plot. Ann-Christin Rommen, who has collaborated with Wilson in a director’s role numerous times, explains this strategy:

Bob will always try to keep [the text] as open-minded and as inexpressive as possible. He doesn’t want [the actors] to express the meaning too much. He wants them to leave it open for the audiences to experience and hear it for themselves and make up their own mind.

Indeed, Wilson has always been willing to consider interpretation the most collaborative of exercises. He has always hoped that each spectator, each critic, each performer might approach his work directly and truthfully, through eyes that have begun to listen.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: kommersantru

Роберт Уилсон, пятидесятипятилетний уроженец штата Техас, оказался востребован в Европе гораздо больше, чем у себя на родине. Старый Свет больше двадцати лет назад впервые испытал на себе наркотический эффект уилсоновского театра и с тех пор прочно “подсел” на Боба (в театральном мире режиссера привыкли называть уменьшительным именем). Его часто упрекают в том, что все его спектакли похожи один на другой. На что Уилсон всегда отвечает одинаково: про Сезанна тоже можно сказать, что он всю жизнь писал одну и ту же картину.

До сих пор похожий на долговязого вундеркинда-компьютерщика, Уилсон сегодня — едва ли не самый плодовитый, удачливый и дорогой (в смысле гонораров) театральный постановщик. Он уже не считается авангардистом-новатором, каким был лет двадцать назад, но еще не перешел в ареопаг ископаемых царствующих классиков, находясь, таким образом, в зените славы и продолжая быть весьма актуальной фигурой.

Уилсону удалось то, что в последние десятилетия не удавалось почти никому. Прославиться и занести свои имена в театральные анналы сумели многие европейские экспериментаторы-шестидесятники, но создать собственный новый театральный язык не получалось почти ни у кого. Кроме Боба. Когда его попросили коротко определить суть его стиля, Уилсон ответил неопределенно, но красиво: театр — это кубик хрусталя в сердцевине спелого яблока.

Аутизм, от которого Уилсон был излечен в детстве, оставил в сознании режиссера стойкое недоверие к литературным текстам. То, как говорится слово, для минималиста Уилсона несравненно важнее того, что оно обозначает. Поэтому и облик вещей в его театре никак не связан с их названием. Уилсон успешно борется с живыми эмоциями на сцене и виртуозно работает с музыкой и светом. Он выстраивает ослепительно красивые статичные композиции и никогда не ошибается в предварительных расчетах. Он ценит европейскую актерскую школу и ненавидит поиски смысла в театре. Вообще, привычное первенство человека на театральных подмостках он отменил.

Все элементы в спектаклях Уилсона равнозначны. Обычный стул или луч света он заставляет “играть” наравне с актером. Архитектор по образованию, он предоставляет слово прежде всего пространству. Соотношение человека и предмета в театре Уилсона все время меняется и зависит от малейшего движения. В приезжающей в Москву “Персефоне” всего один жест — будь то резко отставленная в сторону рука Поэта-рассказчика или безвольно запрокинутая кисть танцовщицы — может оказаться столь значительным, что организует и подчиняет себе все пространство. Кажется, что Уилсон сидит за особым пультом, откуда он незаметным движением фокусирует в любой точке сцены пронизывающие ее невидимые силовые линии.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: nyfilmetcexblogjp

ウィルソンはマルチ・メディアを用いた舞台セットのパイオニアであり、いわゆる“前衛”舞台芸術をメジャーにすることに貢献したアーティストである。彼の作品は1970年代初めからニューヨークやヨーロッパ各地で上演されるようになり、芝居にダンス、オペラとジャンルも幅広い。現在65歳になる彼は世界各地の芸術団体から依頼されたプロジェクト10以上を同時進行させるという売れっ子ぶり。舞台作品の演出・デザイン以外にも、数年前にグッゲンハイム美術館で開かれたジョルジョ・アルマーニ展の照明も手がけたり、自分自身がハムレットを演じたりと、多彩な活動をしている。

このドキュメンタリーの魅力は、まず、大学時代に彼自身が踊った作品から、最近のオペラまで、過去40年間にわたる彼の作品の抜粋が見れること。初期の、ひょんなことから彼が引き取ることになった障害児を主演させた作品や、革命前のイランで数日間ぶっとおしで屋外上演した作品(彼自身も含めて多くが脱水症状を起こした)、知り合いの自閉症児からアイデアを得た”A Letter for Queen Victoria”(1974年)など、珍しい映像が豊富。

そして、ロバート・ウィルソン自身による回想が面白い。テキサスの名家に生まれたが、母親は愛情表現の薄い人で、父親は頑固な保守主義者。幼年時代は、ひどい吃音症と学習障害で惨めな学校生活を送っていたが、あるバレエ教師に何気なく「もっとゆっくりしゃべるようにしてみれば?」と言われたことがきっかけで、1年以内に普通にしゃべれるようになったそうだ。彼の同性愛は「直せる」と信じていた父親の意向で、テキサス大学に入学してロースクール(!)を一度はめざすものの、アートへの興味が捨てきれず、ニューヨークへ。60年代初めのニューヨークは、ポップアートが注目を集め、公民権運動も盛んになり始めた頃。水を得た魚のようにクリエイティビティを発揮し始めた彼は、自分の演劇グループを作って、次々と新作を上演するようになる。自己を束縛から解放し、同じような夢やテイストを持つ人間と知り合える場所としてのニューヨークの役割は、多くのアーティストに共通している。そう言えば、彼だけでなく、サム・シェパードやルー・リードも同じようなことを書いていた。

ウィルソンの舞台では、しばしば俳優たちの動きはおそろしくスローだが、吃音症を克服するきっかけになった女性のことばが関係あるのかもしれない。後年、若手アーティストの育成に力を注ぐようになったことについて、学習障害で苦しんだ自分の経験から、教師の力の偉大さを知っているからだと語っている。

また、親友は一家の使用人の息子だったが、彼が黒人だったために、つきあいは禁じられていた(当時は、人種差別が合法だった)。しかし、こっそりと、その友人とよく黒人の教会に行って、熱狂的な説教や霊歌を聴いたという。「それがすべてポジティブなメッセージだったのが印象的だった」と語っているが、ウィルソンにとって、それが最初のパフォーミング・アーツ体験、異文化体験だったのだろう。

驚いたのは、テキサス時代は内向的で、家庭でもコミュニティでも居場所がないと感じていたウィルソンが、すぐにプロデューサーとしての才能も発揮し始めたこと。人を集めて動かすのがうまく、”Einstein on the Beach”がメトロポリタン・オペラ劇場で上演されたときは、彼自身がプロデュースした。「チケットは2000ドルから2ドルですぐ売り切れになった。わざと2ドルの席を2000ドルの席の隣にしたんだよ(笑)」。(つまり、寄付金つきの高いチケットを買った金持ちの隣に、若い貧乏学生が座ったのである。)なるほど、プロデューサー的手腕は、前衛からメジャーになれた大きな要素だったにちがいない。

セット準備中や演出中のウィルソンを撮影したシーンを見ると、黒沢明に負けず劣らず、おそろしく口の悪い完璧主義者。手の動きについて彼から細かい注文を受けたイザベル・ユペールは心なしか頬がぴくぴくしている。ウィルソンはエネルギーも人一倍高く、少ない睡眠時間でも機能し、飛行機の中でもアイデアをスケッチしている。スタッフは彼のエネルギーについてゆくのが大変そう。

ロバート・ウィルソンは既に世界ブランドなので、何をやっても客が集まる状態。これはある意味では危険なことでもあるのだが、彼のはてしない好奇心と精力的な制作姿勢はずっと変わっていない。

若手の育成という目的に加えて、自分の感性を磨くという意味でもあるのだろうが、ロング・アイランドにある自分の財団で、夏にジャンルを超えた、世界各地からのアーティストたちを集めてワークショップを行っている。毎年、30カ国近くから100人近くが参加するとのこと。ダンサーのバリシニコフにしろ、彼にしろ、私財と寄付でこういった施設を作って、アート・コミュニティに貢献しているのには感心する。

このドキュメンタリーの中で、”Einstein on the Beach”を40回以上見たというスーザン・ソンタグが「彼の成功はアートに助成金を出すヨーロッパでの活躍のおかげ。アメリカでだけだったら、彼は絶対ここまでにはなれなかった」と語っているが、日本はアメリカよりもはるかに助成金制度は整っていない。だいたい、賞金つきの賞や補助金を、既に成功した芸術家に出すのはひどくばかげている。財政援助やPRが必要なのは、まだ芽の出ていないアーティスト、商業的に自立できないアーティストなのに。