Tony Oursler

Оуслер, Тони

ID

source: thecreatorsproject

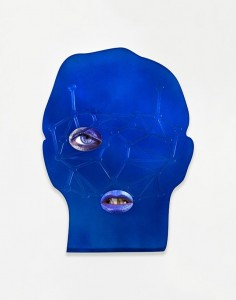

Walk into the Lisson Gallery off London’s Edgware Road and you’ll be greeted by rooms full of peering, uncanny masks, some of them recognizble as human faces, others distorted, reassembled abstractions with just an eye and mouth hanging there. Something’s amiss.

These unusual portraits are part of American artist Tony Oursler’s artist’s first UK show in five years, template/variant/friend/stranger, that explores the human face as filtered through the aesthetics of surveillance. Using biometrics, and facial recognition to inform the works, the show looks at how our identities are being impacted by the vast collation of data by global security services.

The masks, or portraits, take different forms—one room is full of seven looming photographic faces, each etched with the geometric analysis of facial recognition software, with moving videos for their eyes and mouths.

“We created these machines to extend our desires,” Oursler tells The Creators Project. “It seems like these days they’re pulling away from us, aggregating enormous amounts of data, looking back at us and taking measure of their maker. So there we are, trapped in our own system again, humanity looking out of an algorithmic web.”

As you walk around the gallery the portraits become more surreal. Metallic hoods with facial features cut out from stainless steel jar you with their artificiality. Downstairs, a frantic video projection of 150 algorithmically made eigenfaces—blurry, ghostly machine imaginings of the human face—which flash briskly on a head-shaped screen.

“I stumbled across these creepy images on the internet and was intrigued by the notion of a sort of machine gaze,” Oursler explains of the eigenfaces. “Constantly sifting, shuffling, combining features, viewing as indexical references within a database—eigenfaces seem to do that. My studio interfaced with Dr. Thomas Busey of the Department of Psychological and Brain Studies at Indiana University, and he and his students kindly rendered a group of images for us to use.”

There’s definitely a creepy element to the portraits, which Oursler says comes from our own apprehensiveness towards technologies—especially the biometric kind—and the encroachment on privacy they seem to demand in an increasingly paranoid world, a world that also asks us to be ready for new mixed-realities (virtual and non-virtual) wherein devices like Oculus and Microsoft’s HoloLens will augment our lives and perceptions.

“The viewer is spooked by technology, I don’t have to do that,” explains Oursler. “There are many dark elements at work but simultaneously there are great creative and social leaps to be made. As we unlock those aspects I see a rosy future. But ask anyone who’s been hacked or crashed out what it feels like. Catassing is a spooky state of mind.”

We’re left trying to understand where these technologies are taking us and what kind of invasions we’ll allow them. Artists and designers are already fighting back against surveillance tech with stealth fashions and Faraday cages for our phones, but how realistic is it to think that we’ll actually adopt these countersurveillance measures into our lives? It all seems so sci-fi right now, too much like William Gibson novels. Could you see your mom rocking Adam Harvey’s CV Dazzle look?

“As it turns out, science fiction is just as neurotic as we are,” Oursler notes. “Phillip K Dick was correct about that: we are going to drag faults and human abstractions into the future. Perhaps these things are what makes us human and interesting to begin with. For the Lisson show, I made some video of camo-designs that are supposed to confuse facial recognition algorithms, people have been playing with this in clothing design and make up. It was projected with the eigenfaces as a kind of push back. One can imagine a whole industry built up around privacy and/or protecting these flaws. Maybe, subliminally, that’s how all this technology is functioning right now.”

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: lissongallery

Always rooted in the medium of film, Tony Oursler conjures sculptural and immersive experiences using technologies that hark back to magic lanterns, Victorian light shows, camera obscura and auratic parlour tricks, but that also look forward to the fully networked, digitally assisted future of image and identity production. As a pioneer of video art in early 1980s New York, Oursler specialised in hallucinogenic dramaturgy and radical formal experimentation, employing animation, montage and live action: “My early idea of what could be art for my generation was an exploded TV.” From performative and low-fi beginnings, Oursler has developed an ever-evolving multimedia and audio-visual practice utilising projections, video screens, sculptures and optical devices, which might take form as figurative puppets, ethereal talking automatons or immersive, cacophonous environments. His enduring fascination for the conjunctions between the diametrically opposed worlds of science and spiritualism have allowed him to explore all kinds of occult and mystical phenomena, employing not just smoke and mirrors, but playing the role of circus showman and extricating the sham from the shaman. Oursler’s aesthetic and interactive technomancy reveals not only the ghosts in the machine, but the psychological impact of humanity’s headlong dive into cyberspace.

Tony Oursler lives and works in New York. Born in 1957, he graduated from the California Institute of the Arts and collaborated on early works with artists such as Mike Kelley. His museum exhibitions include Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (2014); Pinchuk Art Centre, Kiev (2013); ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, Denmark (2012); Helsinki City Art Museum, Finland, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2005); Kunsthaus Bregenz (2001); Whitney Museum, New York (2000) and Kunstverein Hannover, Germany (1998). In addition to participating in prestigious group exhibitions such as Documenta VIII and IX, Oursler’s work is included in many public collections worldwide, including the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC; Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Museum of Osaka, Japan; Tate Gallery, London; Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven and ZMK/Center for Art & Media, Karlsruhe, Germany.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: eaiorg

Tony Oursler’s brand of low-tech, expressionistic video theater is singular in contemporary art. Willfully primitive, often grotesque, and crafted with an ingenious visual shorthand, his psychodramatic landscapes of image and text are fabricated within the ironic vernacular of pop culture.

Oursler has worked in installation, painting, sculpture, and video since the mid-1970s. His recent mixed media installations, in which theatrical objects such as puppets and dolls are layered with video projections and spoken text, are prefigured in the wildly inventive body of videotapes that he has produced over the past twenty years.

In his single-channel video works, Oursler’s idiosyncratic fictions take the form of bizarre narrative odysseys, horror-comedies that evoke Caligari by way of Eraserhead. Subjective visions of cultural and psychosexual delirium are pursued with outrageous black humor and a surreal theatricality.

The miniaturized, hand-constructed and painted mixed-media sets that are Oursler’s signature suggest post-punk spectacles via German Expressionism; his somnambulant voiceovers and disorienting sound collages evoke stream-of-consciousness dreamstates. To enter one of his insular universes is to embark on a twisted journey that assumes the form and content of a hallucination of the contemporary collective unconscious. Strewn with the objects and idioms of adolescent fantasies, the detritus of mass cultural artifacts, and the macabre inversions of nightmares, Oursler’s elaborate theatrical microcosms are populated by jerry-rigged props, hand-made puppets, found objects, body parts and, at times, human actors.

Fusing media-saturated artifice with primal obsessions, the iconography of his visual tableaux ranges from the biblical to the perverse; the language of his narrated texts is hilarious, irreverent and unexpectedly poetic. Utilizing low-tech gadgets to simulate and satirize video effects, his disjunctive fictions are haunted by themes of sexual alienation and hysteria, political and cultural violence, and the dichotomies of good and evil, life and death.

Early works, such as The Weak Bullet (1980) and Grand Mal (1981), have been described as “half Jackson Pollack, half David Cronenberg, and as funny as [they are] paranoid.” The faux-naivete of his visual and spoken tales belies the textual sophistication of his meta-language of pop culture and subversion of narrative modes.

In the late 1980s Oursler increasingly used his narrative and visual strategies to construct social critiques. His more recent installation works continue to explore a kind of macabre psychodramatic theater with pop cultural elements. Fantastic Prayers, a 1999 CD-ROM project that translates many of these themes into an interactive format, is a collaboration of Oursler, writer Constance DeJong and composer/musician Stephen Vitiello.

Oursler’s exploration of sound has led from stream-of-consciousness narration and voiceover of inanimate objects to collaborations with acclaimed musicians and sound artists. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, he experimented with sound and collaborated with Mike Kelley and John Miller as part of The Poetics, an “art band” that united the artists’ interest in music and performance. The 1990 Tunic (Song for Karen), a music video made in collaboration with and starring Sonic Youth, merges Oursler’s distinctive visual strategies with Sonic Youth’s rock critique of the relation of celebrity, gender and body image. Works such as >Pop, a 1999 video portrait of musician Beck, Empty (2000), with David Bowie voicing text by Oursler, and Sound Digressions in Seven Colors, which features seven sound artists, are more recent collaborations with musicians. Oursler was born in 1957. He studied at Rockland Community College, Suffern, New York, and received a B.F.A. from the California Institute for the Arts, Valencia, where he studied under John Baldessari.

Oursler’s videos and installations have been widely exhibited internationally, including one-person shows at Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Centre d’Art Contemporain, Geneva; Musée D’Orsay, Paris; Kunstverein, Hannover, Germany; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE); Jeu de Paume, Paris; Metro Pictures, New York; Lisson Gallery, London; Nyehaus, New York; Lehmann Maupin, New York; Museum Fur Gegenwartskunst, Basel; and the Museo D’Arte Contemporanea, Rome; among others. In 1999, a mid-career retrospective of Oursler’s work was exhibited at Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, and toured to The Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston and Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. His work has also been seen in group shows at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.; Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels; Documentas IIX and X, Kassel, Germany; The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial, New York; the Tate Gallery, London; and DuMont Kunsthalle, Cologne.

Oursler lives in New York.