MANFRED MOHR

CUBIC LIMIT

source:emohrcom

Manfred Mohr is considered a pioneer of digital art. After discovering Prof. Max Bense’s information aesthetics in the early 1960’s, Mohr’s artistic thinking was radically changed. Within a few years, his art transformed from abstract expressionism to computer generated algorithmic geometry. Encouraged by the computer music composer Pierre Barbaud whom he met in 1967, Mohr programmed his first computer drawings in 1969.

Some of the collections in which he is represented: Centre Pompidou, Paris; ZKM | Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe; Joseph Albers Museum, Bottrop; Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Chicago; Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Ludwig Museum, Cologne; Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen; Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, Stuttgart; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Museum im Kulturspeicher, Würzburg; Kunsthalle Bremen, Bremen; Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain, Strasbourg; Daimler Art Collection Berlin / Stuttgart; Musée d’Art Contemporain, Montreal; The Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv; Espace D’Art Concret (EAC), Mouans- Sartoux; Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Cologne; Borusan Art Collection, Istanbul; McCrory Collection, New York; Esther Grether Collection, Basel; Thoma Art Foundation, Chicago.

Mohr has had many one-person shows / retrospectives in museums and galleries like: ARC – Musée d’Art Moderne de la ville de Paris, Paris 1971; Joseph Albers Museum, Bottrop 1998; Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen 1987, 2002; Museum for Concrete Art, Ingolstadt 2001; Kunsthalle Bremen, Bremen 2007; Museum im Kulturspeicher, Würzburg 2005; Grazyna Kulczyk Foundation, Poznan 2007; ZKM – Media Museum, Karlsruhe 2013; Featured Artist at Art Basel, Basel 2013; Center for the Arts, Virginia Tech 2014; Simons Center Gallery, Stony Brook 2015; Kunstverein, Pforzheim 1988, 2008; Museum Pforzheim Gallery, Pforzheim 1998, 2017.

He took part in innumerable group shows for example at: MoMA – Museum of Modern Art, New York 1980; MoMA-PS1, New York 2008; Centre Pompidou, Paris 1978, 1992, 2018; ZKM | Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe 2005, 2008, 2010, 2018, 2019; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York 2019; Grand Palais, Paris 2018; Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin 2018; Prague City Gallery (G HMP), Prague 2018; Victoria and Albert Museum (V & A), London 2009, 2018; Whitechapel Gallery, London 2016; CCCB, Barcelona 2016; Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, Stuttgart 2005, 2009, 2011, 2012, 2015, 2016, 2017; Kunstmuseum Bremen, Bremen 2007, 2017, 2018; Vasarely Museum, Budapest, 2007, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2017, 2018; Espace D’Art Concret (EAC), Mouans- Sartoux 1994, 1995, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2009, 2012, 2018; Museum Ritter, Waldenbuch 2005, 2006, 2008, 2013; Centro Cultural de la Villa, Madrid 1989; MoCA, Los Angeles 1975; National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo 1984; Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco 1973, 1977, 1980; MACM – Musée d’Art Contemporain, Montreal 1974, 1985, 2013; Fundacion Banco Santander, Madrid 2014; Muzeum Sztuki, Lodz 1981, 2011; Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, 1999; New Tendencies 5, Zagreb 1973; Leo Castelli Gallery, New York 1978; Galerie Paul Facchetti, Paris 1965 und Zürich 1970.

Among the awards he received are: elected to the SIGGRAPH Academy, 2018; ACM SIGGRAPH Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement in Digital Art, 2013; [ddaa] d.velop Digital Art Award, Berlin 2006; Artist Fellowship, New York Foundation of the Arts, New York 1997; Golden Nica from Ars Electronica, Linz 1990; Camille Graesser-Preis, Zürich 1990.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source:medienkunstnetzde

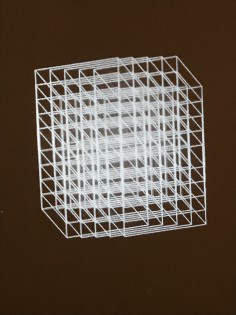

In «Cubic Limit,» Mohr introduces the cube into his work as a fixed system with which signs are generated. In the first part of this work phase (1972–75), an alphabet of signs is created from the twelve lines of a cube. In some works, statistics and rotation are used in the algorithm to generate signs. In others, combinatorial, logical and additive operators generate the global and local structures of the images.

In the second part of this work phase (1975–77), cubes are divided into two parts by one of the Cartesian planes. For each image the two partitions contain independent rotations of a cube. They are projected into two dimensions and clipped by a square window (the projection of a cube at 0.0.0 degrees). By rotating both parts of these cubes in small but different increments, long sequences of images are developed.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source:bitformsart

Cubic Limit

During Manfred Mohr’s legendary 1971 exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, he met the CEO of a data storage and preservation company, which specialized in microfilm. Mohr was invited to experiment on their brand new machine to make computer animations. Mohr accepted and during the next four years made several short computer films, such as Cubic Limit. According to Mohr, “it was a very painful experience since the process was very slow and the turnover dragged out over many months.”

Each frame was drawn in high resolution with a light beam directly from the computer onto 16mm film to create the animations. How did you come up with the idea to use this computer to create moving images? I made several short 16mm computer films in the early 1970’s. In 1971, at ARC in Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, I showed my work calculated and drawn by a computer, which was a first in a museum at that time. During that show I made demonstrations of plotter drawings. On one occasion I met the CEO of La Compagnie Générale de Micromatique, a graphic company. He invited me to experiment on their graphic machines. I had no prior knowledge of this graphic machine, which by the way, is not a computer as it only renders a pre-calculated digital result from a computer into graphics.

At that moment in time I was also struggling with some other philosophical problem about computer generated graphics. I had so many ideas every day that I could not program fast enough to bring them all on paper. I realised that all my ideas were so diverse, and yet did not really have a common theme. Going back to my music background, I dreamt of inventing a sort of musical instrument on which I could play “graphics” that would be recognisable with a common theme. If I play saxophone, no matter what I play, it would always sound like a saxophone. Then the cube came to my mind and I immediately adopted it as my instrument: A rigid structure of 12 lines and fixed relationships (later expanded into n-dimensional hyper-cubes) Visual equations of cubes, plotter drawings on paper, 1975. This became my vocabulary, and the connection to the above mentioned CEO came just in time to experiment with a rotating cube as a moving image. It was also the time when I was very interested in the mathematician René Thom and his idea of a ‘catastrophe point’. I wanted to experience the moment (catastrophe point) when a rotating cube was not anymore recognisable and dissolved into just abstract lines.

In which language did you write Cubic Limit?

I programmed in FORTRAN IV and ran the program at the institute of Meteorology in Paris, where I had access at the time. I wrote the results on magnetic tape, which I then brought to the company to execute it on their graphic machine. From a small internal screen, a camera made a 16mm film. Since I had no experience in filmmaking, it took me a while to figure out all the programming details of filming, speed, size etc. I had to write all the software myself because nothing existed in this field at that time. From the moment of delivering the tape and the finished 16mm film it took weeks, and since I had no priority, sometimes months. After three years I lost patience and interest. I have an archive in Germany of print-outs of most of my early programs. You might not realise at that time one wrote programs on punched cards. I have about 10,000 punched cards sitting there. Here in New York, I have most of the basic printed code because I always made books of my computer printouts for my own reference and the pleasure of making books.

You say the work of Max Bense altered the way you look at the world. I came upon Bense by accident. A friend of mine who studied Philosophy suggested that I read Bense’s poetry in the early 1960’s. I did, and got so impressed

by the language, that I also bought his philosophical writings Aesthetica IV, which contained the four books

he wrote since 1952. I slowly realised that the ideas he developed corresponded to something I was unconsciously seeking for a long time. I was very much interested in the content of what I was doing as an artist, and less in emotions. Through Bense I got the lead of where to go. A few years later I was ready to write algorithms of my ideas. I was irreversibly attached to the fact that I can create a visual result from a non-visual logic. Since knowledge is irreversible, up to this day when I see an artwork, my mind looks immediately for its logical content. I cannot and I do not want to return to emotional expressions.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source:grandpalaisfr

Manfred Mohr place les algorithmes, la géométrie et les mathématiques au coeur de sa pratique artistique. Prises comme point de départ, les mathématiques sont transcendées pour devenir une partition combinatoire évolutive où chaque forme tracée émerge à partir de celle qui l’a précédée.

Pionnier de l’art génératif et informatique, Manfred Mohr (1938, Pforzheim, Allemagne) commence sa carrière artistique sous l’influence de l’expressionnisme abstrait. Mais la découverte de la pensée du philosophe allemand Max Bense sur l’esthétique de l’information et le travail du compositeur français Pierre Barbaud sur la musique générée par ordinateur vont changer radicalement son approche. Il se tourne alors vers la géométrie et les algorithmes et, en 1969, commence à réaliser ses premiers dessins par ordinateur avec un traceur à l’Institut de météorologie de Paris, où il vit à l’époque.

Depuis, Mohr travaille exclusivement par ordinateur, développant des algorithmes qui donnent forme à ses idées visuelles. Son motif principal est l’hypercube, un cube de plus de trois dimensions, qui peut seulement être partiellement représenté dans un espace bidimensionnel. En 1971, l’exposition Computer Graphics, une esthétique programmée au Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris devient la première exposition monographique d’art informatique dans un musée.

Présenté dans l’expo Artistes & Robots, Cubic Limit a été présenté lors de son exposition Computer Graphics en 1971, où Mohr était invité par la Compagnie générale de micromatique à expérimenter leur nouvelle machine graphique. Ce film est le premier travail où Mohr utilise le cube comme un alphabet pour « écrire » une série de signes visuels abstraits. Chaque élément cubique apparaît dans une grille, produisant une image en mouvement d’un cube en rotation. Un cube est divisé horizontalement en deux parties par l’un des plans cartésiens. Pour chaque image, les deux partitions contiennent des rotations indépendantes d’un cube qui sont projetées en deux dimensions et rognées par une fenêtre carrée. En faisant tourner les deux partitions du cube par de petits mais différents incréments, Cubic Limit crée de nouvelles relations visuelles en fracturant la symétrie du cube. Chaque image du film a été dessinée en haute résolution par un faisceau lumineux directement depuis un ordinateur sur un film 16 mm. L’artiste présente également dans l’exposition Artistes & Robots l’oeuvre P-200-E, une série de 46 dessins réalisés avec un traceur qui interroge la structure du cube.