KATIE PATERSON

Light-Bulb to Simulate Moonlight

source: glasstire

Existing somewhere between visual poetry, scientific investigation and environmental loss is the work of Katie Paterson. It is quiet and blue (sometimes in color and sometimes in emotion) and seems to reflect the pace of a glacier but much like glacial ice it contains many layers of complex issues within its minimal form. Stratums that can only be unpacked by a viewer willing to take the time to both look and listen.

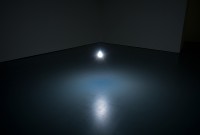

Her work is multidisciplinary, conceptually driven and often the result of intensive research and collaboration with experts in fields outside of the arts. One example, and a piece best viewed if you can alone, is Light Bulb to Simulate Moonlight – an installation that consists of a lifetime of incandescent bulbs designed to simulate moonlight. For this piece Paterson worked with a manufacturer to develop and produce a unique bulb that emits the identical light, in terms of color temperature, wavelength, and amperage, given off by a full moon. When the working bulb burns out, it is replaced with a new one. There are a total of 289 bulbs mounted on the wall in a shelving system with one open slot for the moon bulb in use. Each one is meant to burn 2,000 hours and last 66 years, which was the average human life span in 2008.

For Langjökull, Snæfellsjökull, Solheimajökull, the names of three glaciers in Iceland, three monitors play three separate videos of sound recordings. The glacial sounds were collected, cast from melted ice that had been taken from the glaciers and frozen into ice records. The videos document not only their thaw but also the breakdown of an environment—wind and water. Played on turntables the records start out clean and flat- physical documents made of ice and ambient noise. As they play and slowly break down they are dissolved by the needle, the warm air and ultimately end in a pool of scratchy sounds and dirty sludge.

All the Dead Stars is a large laser etched map on black anodized aluminum that shows the locations of every dead star in the universe, 27,000 in total. In it, our galaxy is indicated by marks on the surface that form a horizontal line across the map’s center. Standing in front of it you see a loss that is larger than each one of us, a realization which is both beautiful and sad. Like all of the work in this exhibition it suggests a dependent relationship with nature and as a consequence it’s impact on us as well as ours on this planet Earth.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: jotta

‘Light Show’ features sculptures and installations that use light in order to affect our sense of space, perception, and vision. The exhibition spans the past fifty years of light being used as a medium within art, including work by some of the earliest innovators as well as new artworks created especially for the show. These intangible sculptures and immersive installations give us the opportunity to explore light and all its facets, from colour to duration, heat to projection, as well as its impact on our senses.

The earliest work in the exhibition is that of Dan Flavin, labeled as the pioneer of Light art, he created his first fluorescent works in the early 1960’s. The fluorescent tube structures were a natural progression for Flavin from earlier works – sculptural pieces containing incandescent bulbs. Within light show, we see The Nominal Three (to William of Ockham) which references ‘Ockham’s Razor’ – the nominalist philosophic principle that advocates succinctness and parsimony, and reflects his desire to limit the number of elements that form his work.

The stark, minimalist structures are still impressive fifty years since their inception, and the seductive nature of light overcomes the outdated, florescent tube casings. This now defunct lighting fixture, chosen by Flavin due to it’s common availability, has become difficult to obtain. As a result, a number of museums and collectors have begun commissioning custom made replicas of the traditional bulbs in order to extend the lifespan of the work. In some ways, this goes against the artist’s intentions. Not only did he believe that only readily available materials should be used, but that they should advocate a state of impermanence. Flavin relished in the temporal ‘on and off’ qualities of his pieces that could be ‘controlled by a switch’, and the inevitability that one day they would fully expire to leave ‘nothing but rust and glass’.

In the 1960s, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art launched an ambitious programme that paired artists with pre-eminent scientists. Already having studied perceptual psychology, it was here that James Turrell, was able to demonstrate visually his investigations into light and perception. Included in light show is Turrell’s Wedgeworks V (1974) . An installation consisting of a darkened room within which the viewer is presented with an illuminated, dimensionally ambiguous space. The installation is to be experienced over a period of ten to fifteen minutes, within this time, eyes adjust to see the space in different ways. The intent, of this concentrated state is for the viewer to recognise this change in perception, for them to notice the act of vision.

In this work, and across others within the exhibition, light is used in a way the which creates the illusion of structure and tangibility despite it being an immaterial substance. Turrell’s belief that ‘through light, space can be formed without physical material” is demonstrated by Wedgework V within which, the beams of coloured light allude to being solid objects which divide the room.

We can also experience light as a ‘solid’ object in avant-garde filmmaker Anthony Mccall’s You and I Horizontal (2005). A shape-shifting beam of light emanates from a projector, and is made visible by vapour created by a haze machine. It offers the opportunity for interaction with the light and when passing through it, the viewer is wrapped in a cone of light, drawn to the source and the structure it creates. The immersive illusion of Chromosaturation (1965) by Carlos Cruz-Diez is made up of three pure white rooms, one illuminated in red, one in blue and one in green. It plays with the viewer’s colour receptors and is overwhelming and disorientating, the colour takes on an almost material physicality. Illusion is also used by Olafur Eliasson in his piece Model for a Timeless Garden (2011), which is made up of a series of 27 different fountains illuminated by strobe. Although the effects of strobe-lighting are more familiar than the techniques used by Turell and Cruz-Diez, they are used so dramatically that their impact is truly impressive, turning fountains into ever-changing, dancing ice-sculptures.

Other artworks make us consider the way we react to different intensities of light. Katie Paterson’s Light Bulb to Simulate Moonlight (2008), does exactly that, creating a subdued, subtle illumination. Through the associations that are so embedded within our collective memory, it evokes all the qualities of night, it’s stillness, it’s quiet. In contrast, Cerith Wyn Evans’ S=U=P=E=R=S=T=R=U=C=T=U=R=E (2010), is made up of three pillars of light that dim and glow intermittently. At their brightest, they are blinding, and the warmth emanating from them is both attractive and compelling.

The sheer power of light to draw us in and affect our senses and perception is perfectly illustrated through the work that is on display at “Light Show”. This exhibition reminds us of light’s importance as a medium within art, unique in it’s ability to be completely immersive, yet intangible and illusive.