STEVEN CLAYDON

source: theguardian

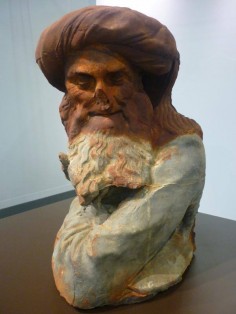

Steven Claydon’s art almost comes from another dimension: one that must be a lot like Earth, but where history’s out of sync and culture’s all jumbled up. His arrangements of objects on sack cloth-covered screens and boxy stands recall the musty exhibition style of old museums. But the artefacts they display seem out of step with time. Take his resin heads: they recall classical marble busts, but what’s with the retro space-age bobbed wig, gold bouffant or Bart Simpson complexion?

What would future societies make of Claydon’s meticulously presented skeins of yellow electric cable, or lovingly fashioned wood offcut sculptures, if they came across them buried in the sand? They would surely have a job deciphering the elusive references at play in his sculptures, photos, paintings and videos. You’ll be as likely to find modernist architecture meeting ancient myth as the Smurfs getting cosy with the similarly stocking-capped philosopher, Heidegger. Claydon’s allusions are deliberately teasing and hard to pin down, born of his rewriting of history as marvellous “what ifs”. They nod to the infinite complexity of how art and culture comes to be. Claydon’s mysterious fusions of old and new, raw and manmade, include a large plastic industrial oil drum presented like a ceremonial urn beside a rough clay idol with teat-like studs and a foil mandala made from Mylar, the material of astronauts’ space blankets, and embossed with cartoon characters. Atoms and pixels might be the literal origins of the things we see, but an object’s cultural resonances are far harder to pin down.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: moussemagazine

He works with Hotel, one of the trendiest galleries in London (you’ve already heard of it around here). His résumé boasts, among the other things, a solo show at White Columns in New York. But clearly, he was not satisfied. So Steven Claydon experimented with the role of curator, and he put together a group exhibition currently on display at the Camden Arts Centre in London (until February 10) that counts no less than some forty artists. A oddly-titled catalogue of styles and works that ranges from the turn of the century to these days, from certain obscure heroes of British Modernism to Carol Bove. We had the suspect that this little pantheon was worshipped not only by Claydon but by a whole generation of artists, especially British ones. And we wanted to know something more about it.

Let’s start from the exhibition you curated at the Camden Art Center in London, Strange Events Permit Themselves The Luxury Of Occurring. To begin, tell me something about its title.

The title comes from an aphorism quoted from a fictional character. As well as empathizing with the fugitive sentiment of this maxim, I was curious as to whether a quotation from a fictional character is any more or less relevant owing to its spurious nature.

The intention was to create a climate of practice orbiting an errant core. The worry is always that the event will appear prescriptive/ didactic or conversely, that it is rendered nebulas or flippant. As I was invited to include my own work I felt uncomfortable creating a “top ten” show and including myself within an exclusive lineage. Instead, I sought to create a show that was sympathetic to my own practice. An a-historical, a-parralell, lateral incursion into some neglected territory that provides an alternative reading of the peregrinations of the modern. The show could have taken multiple directions and I think I may have included a very different group of artists for every day that I worked on it. For instance, I would like to have done an alternative neo geo show or a text related show. Instead I chose to dwell on the nature of the thinglyness. Looking back I think I would like to have included a Hiem Stienbach but I was lucky enough to be able to include every thing I requested except for a Paul Theck piece that was too fragile to travel and a Picabia that has disappeared off the face of the planet. The backbone of the exhibition is “the relationship between the art objects and the institutions which display them. ” You talked about “taxonomies of display. ” Can you explain this idea more in depth?

History and critical literature relies on a lineal compartmentalization of events in order to rationalize causal events. Institutions evolve modes of display that accommodate these conceits. Likewise, the commercial sector apes the architectural language of the venerable or authoritative. The resulting fallout can loosely be termed “the taxonomies of display” in ironic reference to the flawed attempts of the institution to provide a non-invasive backdrop in which to house the artifact or thing.

I did read it years ago and again towards the end of the curation process and was tempted to include several passages in the accompanying text I produced. However I considered the eccentric way that the show evolved to be independent if not parallel so I decided to omit any reference O’Doherty’s book.

The exhibition at the Camden includes a new installation of yours. I wonder how the creative process of this work has been influenced by its being conceived for an exhibition curated by yourself.

Most of my work is conceived with consideration of the kinds of environments the artifact can be situated, be it an art fair stand or a domestic environment. One can never entirely provide for such eventualities, nor can one impose patronizing comments on the work or viewer. The furniture of display, public and private, are important devices and influence how I construct my pieces. History is a curious and fascinating realm, partially evidential and partially fictitious. The lateral mesh of causal events and absorbed protocol that informs our nature and forms our cultural conditioning should perhaps have a more suitable and complex title but as it is we call it history.

I think the encounter between cultural obsolescence and material longevity is the thing that fascinates me about monumental sculpture. For me it engenders a certain vulnerability despite its intransigent nature.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: artsy

Steven Claydon makes multimedia installations that explore the associative power of objects and the relationship between documentary and fiction. Claydon’s projects—which can include sculpture, video, assemblage, and painting—are often research-based, either examining or challenging commonly held beliefs about history and authority. His works draw from both associations with modern movements and folk artifacts or relics. Displayed in conjunction, the assemblages become intentionally self-contradictory and offer strong statements about colonialism and the permeation of western culture. He also presents these in faux museum-like settings, thereby extending his critical statement to the public institutions that create and display culture.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: thefalmouthconvention

Lives and works in London

Steven Claydon was born in London in 1969. His practice explores the inconsistent relationships that he identifies between writing, representations and objects, most often through perceptive, calculated juxtapositions in a variety of media: sculpture, painting, collage and film.

Through two-dimensional work, sculptures and occasional curatorial projects, Claydon explores the poetic capacity of objects and images – both found and imagined – to gain a certain measure of autonomy when staged against one another within assemblages. He addressed these concerns to a generous extent in the ‘selected by’ exhibition Strange Events Permit Themselves the Luxury of Occurring that he curated at Camden Arts Centre in 2007.

Claydon has participated in performance programmes, with The Ancient Set at London’s Serpentine Gallery, and as part of a Turin-wide performance season The Fifth Dimension, curated by Andrea Bellini in November 2009. He is also renowned as a musician and was a founding member of the band ADD N to (X) until 2003, Jack Too Jack, until 2007, and currently Longmeg.

Steven Claydon has most recently participated in exhibitions including The Dark Monarch, Tate St Ives; Golden Zeiten, Haus der Kunst, Munich; and Dune, curated by Tom Morton at The Drawing Room, London and Plymouth Arts Centre. Previously he has been part of The Busan Biennial, South Korea (2008); Sympathy For The Devil, Art and Rock and Roll Since 1967 at the Museum Of Contemporary Art, Chicago (2007); and Rings of Saturn at Tate Modern, London (2007). He is the artist member of Tate St Ives Council.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: flashartonline

Io ho dei dubbi sul Modernismo, e anche su che cosa ci si aspetti dal lavoro di un artista. Per un po’ ho flirtato con questa idea, e ho realizzato che era un buon espediente per orientarsi verso una serie più ampia di problematiche. Pensavo al tuo lavoro, e mi pare che la tua relazione con il Modernismo sia molto autobiografica, e probabilmente deriva dal fatto che sei cresciuta a Berkley durante un periodo che è stato il “canto del cigno” del Modernismo. La fantascienza ha un ruolo simile per me, dato che considera una proiezione futura alla stregua di un ricordo prezioso. Il fatto che la fantascienza assuma talvolta un ruolo di esperienza concreta per le persone è enigmatico. Mi sono cimentato con l’idea di “fedeltà alla materia”, che è qualcosa di diverso dall’onestà verso i materiali; suppongo si tratti di un’idea che lascia spazio anche all’“infedeltà verso la materia”, o addirittura a un tradimento verso le cose che si producono.