SYLVIE GUILLEM

西尔维·纪莲

シルヴィ·ギエム

Сильви Гиллем

실비 기옘

6000 miles away

source: nytimes

A BALLERINA’S career path is usually predictable. She rises through the ranks of a company, dances principal roles, perhaps performs occasionally with other troupes as a guest artist. If she is lucky — not too many injuries, a resilient body, the right temperament — she may keep dancing into her 40s, carefully tailoring her repertory to her inevitably declining physical capacities.

And then there is Sylvie Guillem.

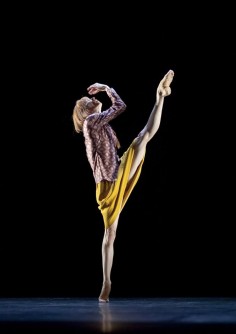

Ms. Guillem, 47, whose program “6000 Miles Away,” presented by the Joyce Theater, will open on Wednesday at the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center, is the stuff of ballet legend. Her steely technique and extraordinary physique — impossibly long, lean and flexible, her cambered feet like prehensile tools — were being talked about even while she was still a student at the Paris Opera Ballet School. When she joined the Paris Opera Ballet in 1981, at 16, she was an almost instant star, a title (“étoile”) officially bestowed upon her by Rudolf Nureyev, the company director, just three years later.

To the shock of the dance world she left the company at 23, citing a desire for more independence, and moved to the Royal Ballet as a principal guest artist. Unlike almost any other ballet dancer — only Mikhail Baryshnikov, and to some extent Nureyev, come to mind — she not only went on to have a superstar career as an interpreter of the classics but also made an apparently effortless transition into works by contemporary choreographers while remaining a big-name box-office draw.

“I don’t think anyone else could do what she has done,” said Brigitte Lefèvre, director of the Paris Opera Ballet. “She has incredible physical and mental strength, and a great deal of courage to put herself out there. The audience appreciates that. She has great choreographers who create work for her, but the public really just wants to see Sylvie Guillem.”

Ms. Guillem’s physical powers seem as tremendous as they were a decade ago. Last year she danced the title role of Kenneth MacMillan’s “Manon” at La Scala to rapturous acclaim; since the July premiere of “6000 Miles” she has been touring with the program, which features demanding works created for her by William Forsythe and Mats Ek. (An extract from Jiri Kylian’s “27’52,” danced by Aurélie Cayla and Lukas Timulak, is also on the program.)

What keeps her going? “For me it is all about pleasure,” Ms. Guillem (pronounced GHEE-lem) said, speaking in fluent English at her Paris hotel. “It is impossible for me to do something without believing in it, enjoying it fully.”

She looked a lot smaller in person than onstage. She was dressed in a long white shirt over dark pants. Her elegant, elongated limbs were camouflaged, and her pale, makeup-free face seemed girlish. She was friendly and articulate, a far cry from the divalike portrait frequently painted by the news media. “I think it was much more difficult for her as a woman to be someone who knew her own mind and spoke it,” Mr. Forsythe said in a telephone interview. “What I really object to is the nickname, ‘Mademoiselle Non,’ that she was given while at the Royal Ballet. It was a way of undermining her, of turning her into a petulant diva who wouldn’t threaten an institution.”

Mr. Forsythe first met Ms. Guillem in 1983, when she was a shy 18-year-old whom he cast in his first work for the Paris Opera, “France/Dance.” Four years later he would create “In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated” for Ms. Guillem and a number of other brilliant young dancers. The piece, which took ballet technique to thrilling extremes, seemed to present a new kind of dancer: fiercely contemporary in approach, utterly real onstage.

It was a way of dancing that perfectly suited Ms. Guillem, who said she didn’t grow up with “the little girl’s fantasy of the tutu and the tiara.” But she seemed surprised when asked whether she was aware of how exceptional her career has been. “If I was aware of it, I’d have to compare myself to others, and I don’t do that,” she said. “I have always just said to myself, I’d like to do this, I’d like to meet this person, and I do it.”

At the Paris Opera “it was always a fight,” she said. “I had a kind of realistic way of being onstage. I didn’t like the fakeness, the conventions of ballet, the things people did without thought because they had always been done that way.”

Ms. Guillem’s desire to make her own decisions, alongside a perpetual hunger to learn, have been the driving forces of her career. Even while dancing the classics all over the world, she was constantly looking for choreographers to work with. “Maybe I still had the reputation of a classical ballerina, doing this,” she said, snapping her fingers imperiously. “But at first it was hard to convince people I was serious.”

In 1996 Ms. Guillem commissioned work from the little-known Jonathan Burrows and Mr. Ek for a film, “Blue Smoke,” and went on to create pieces with Maurice Béjart and David Kern, showing her uncanny ability to integrate widely divergent styles. In 2006 Russell Maliphant choreographed “Push” for her, and that same year she became an associate artist at Sadler’s Wells, later creating works with Robert Lepage and Akram Khan.

“With these choreographers I have felt: I want to be part of that,” she said, “to know what it is, experience it physically and mentally. Trying to absorb different styles is not a challenge, it’s a curiosity.”

She described “6000 Miles,” as showing “three different giants with different languages.” Mr. Forsythe’s “Rearray” is an austere, richly allusive pas de deux (danced with Massimo Murru, a La Scala principal) to an atonal score by David Morrow. Mr. Ek’s “Bye,” set to Beethoven’s final piano sonata (Op. 111), is a solo in which Ms. Guillem interacts with filmed images to generally crowd-pleasing effect.

“Sylvie understood what her talent represented, and she was able to transform that into autonomy,” Mr. Forsythe said. “And she has served as a model. Now other ballerinas, like Diana Vishneva, are doing what she did.”

Ms. Guillem, however, said she never had a plan. She likened her approach to Mr. Forsythe’s choreography: “There is a frame, but you use your instinct.”

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: yourartasia

凡有幸親眼目睹過西薇‧姬蘭(Sylvie Guillem)的現場表演或看過她的舞蹈影片,

一定不會反對稱她為「本世紀芭蕾藝術的最高結晶」!

西薇.姬蘭,出生於法國巴黎,12歲時進入巴黎歌劇院的芭蕾舞蹈學校,她完美的身形、細膩的足部動作、驚人的跳躍能力,加上卓越的領悟力與野心, 讓她成為學校老師們眼中的天才舞者,在16歲時即加入了巴黎歌劇院,18歲時榮獲「芭蕾奧林匹克」之稱的瓦爾納芭蕾大賽金牌獎。

在加入巴黎歌劇院的第三年,當時舞團的藝術總監-紐瑞耶夫,在舞劇「天鵝湖」的演出後,當場向全場觀眾宣布年僅19歲的西薇‧姬蘭成為舞團的首席明星。1986年,紐瑞耶夫更為她量身創作了全本芭蕾舞劇「灰姑娘」。

許多當代大師級編舞家更指名與她合作,結合古典芭蕾的高難度技術與當代創作概念的作品,透過西薇‧姬蘭登峰造極的舞蹈技巧與傳神的演出,將每部作品淋漓盡致的完美詮釋。

「6000哩外」是2011年由英國倫莎德勒之井劇院Sadler’s Wells Theatre與西薇.姬蘭Sylive Guillem共同製作的節目,在排練期間,日本發生了311大地震,西薇.姬蘭為了向受難者致意而特別命名。

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: modenatodayit

Prima italiana al Comunale per “6000 miles away” di Sylvie Guillem.

Sylvie Guillem – Nominata étoile a soli 19 anni da Rudolf Nureyev, è stata fin dai primi anni della sua carriera musa ispiratrice per numerosi coreografi di grande fama quali William Forsythe, Mats Ek e Maurice Béjart. Parallelamente alle sue interpretazioni classiche, l’artista ha riscosso ampi riconoscimenti danzando coreografie contemporanee, oltre che con l’Opéra de Paris, presso la quale si è formata, con il Royal Ballet, l’American Ballet Theatre e il Kirov Ballet, mostrando la completezza delle proprie capacità artistiche. A partire dal 2003 la Guillem si è concentrata sulla danza contemporanea e dalle collaborazioni con gli artisti Russell Maliphant, Akram Khan e Robert Lepage sono nate le coreografie di “Broken Fall”, “Push” (rappresentato in prima nazionale durante la stagione 2006/2007 al Teatro Comunale di Modena), “Sacred Monsters” e “Eonnagata”.

6000 miles away – Lo spettacolo vede Sylvie Guillem impegnata con alcuni lavori dei tre coreografi più importanti dei nostri tempi: William Forsythe, di cui interpreta un nuovo passo a due, Jiří Kylián e Mats Ek, che per lei ha creato il solo Ajö, sancendo inoltre una nuova collaborazione dell’artista con il Sadler’s Wells di Londra.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: zouglagr

«Έπρεπε να υποβάλω τον ευατό μου σε καταστάσεις που με τρόμαξαν» δηλώνει η Sylvie Guillem. Θαυμάστε την Παρισινή χορεύτρια σε αποσπάσματα της παράστασης «6000 Miles Away», όπου με την ερμηνεία της μάγεψε κοινό και κριτικούς σε ολόκληρο τον κόσμο.

Τη χορογραφία υπογράφουν οι Mats Ek, William Forsythe και Jiří Kylián.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: voilatw

Reconnue comme l’une des plus grandes danseuses contemporaines, Sylvie Guillem est la star de cette soirée au cours de laquelle sont présentées des œuvres de trois chorégraphes qui comptent parmi les plus importants aujourd’hui : Mats Ek, William Forsythe et Jiři Kylian.

Cette production Sadmer’s Well/Sylvie Guillem présente le nouveau duo de William Forsythe, Rearray, crée pour elle et l’étoile du ballet de l’opéra de Paris Nicolas le Riche/l’étoile du ballet du Teatro alla Scala, Massimo Murru (qui partage le rôle).

Le nouveau solo du chorégraphe suédois , Bye, crée pour Guillem sur la musique de la dernière sonate de Beethoven, a été qualifiée de chef-d’œuvre par le journal Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.

Enfin, le duo de Kylian, 27’52’’, interprété par des danseurs choisis par le chorégraphe, complète la soirée.

Faisant suite au succès des collaborations de Sadler’s Wells, PUSH et Eonnagata, cette première à Taiwan est un retour à la scène très attendu pour celle qui est considérée comme « la meilleure ballerine de sa génération ».

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: klpteatroit

Ogni arte ha i propri fuoriclasse, e la danza non fa eccezione. Quando però questi ‘numeri uno assoluti’ sfruttano il proprio talento e le proprie risorse per collaborare a un medesimo progetto, i risultati possono essere davvero stupefacenti.

E’ per questo che “6000 miles away” non è soltanto uno spettacolo da antologia, in cui il percorso di Sylvie Guillem, autentica (e forse ultima) “diva” della danza mondiale, si intreccia con quello di William Forsythe, Jiři Kylián e Mats Ek, veri e propri miti viventi della coreografia contemporanea.

Presentato in prima italiana al Teatro Luciano Pavarotti di Modena il lavoro sembra infatti consacrare la volontà, che Guillem persegue ormai da anni, di mettere alla prova le proprie capacità di interprete su più livelli, confrontandosi – abbandonato il repertorio classico – con creazioni di coreografi contemporanei quanto mai diversi l’uno dall’altro.

Prende così vita un programma formidabile, costituito da due brani creati appositamente per la danzatrice francese (“Rearray” di William Forsythe e “Bye” di Mats Ek) a cui si aggiunge un duetto coreografato da Jiři Kylián, intitolato “27’52’’”, con Aurelie Cayla e Lukas Timulak del Nederland Dance Theatre.

Nel duetto “Rearray”, William Forsythe sembra ricollocarsi nel solco di quella tendenza alla decostruzione e ricostruzione della tecnica accademica che aveva caratterizzato i suoi lavori degli anni ’90, e che gli aveva consentito di elaborare a sua volta un linguaggio di movimento autonomo e riconoscibile, fondato sulla disarticolazione radicale di un corpo danzante spinto a esplorare, quasi sempre a velocità supersonica, tutte le possibilità di agire nello spazio e di gestire il proprio peso.

La coreografia, che Sylvie Guillem interpreta insieme a Massimo Murru, si trasforma così in una sorta di costante negoziazione di energie, uno scambio di impulsi nevrotico, elettrico e austero al contempo, in cui i contatti fra i partner assumono la funzione di leve, agganci, ingranaggi che diventano gli snodi attraverso cui si dipana questa effervescente dissezione e proliferazione del movimento.

Un pezzo rigoroso, quasi cervellotico, in cui i danzatori sembrano sfidarsi l’un l’altro mentre lo spazio fra i corpi diventa un campo magnetico carico di concentrazione, caparbietà e anelito al raggiungimento di una forma esplosa eppure ineccepibile.

Le strepitose doti fisiche di Guillem consentono alla danzatrice di incarnare con totale aderenza questo ideale di una forma sempre spinta al limite, si tratti di lavorare sull’iper-estensione delle gambe, sulla rapidità fulminea del salto o sui repentini slittamenti di peso. Sylvie Guillem ci appare qui come un’interprete magneticamente consapevole, enigmatica nel modo di stare in scena e di relazionarsi con movimento virile e quasi ferino, pur nell’assoluto rigore tecnico, di Massimo Murru.

In questo brano l’intelligenza compositiva del coreografo ha modo di esprimersi compiutamente, manifestandosi anche nella fusione perfetta del movimento dei danzatori con la musica (di David Morrow), tanto che si ha come l’impressione che l’impasto sonoro, tagliente e sferzante, si sprigioni proprio a partire dalla danza (e viceversa), il tutto in uno spazio reso costantemente smaterializzato e fluttuante dal ripetuto abbassarsi e rialzarsi delle luci.

Completamente diverso, nello spirito e nella forma, è “27’52’’” di Jiři Kylián. Inquietante, misterioso e struggente, il brano si risolve nella sublime parabola dell’incontro impossibile e tormentato fra un uomo e una donna (gli splendidi Aurelie Cayla e Lukas Timulak): in questo caso il movimento, perennemente percorso da fremiti e contorsioni, trasforma la relazione fra i due in lotta continua, fuga inesausta dell’uno dall’altro, tentativi di contatto appassionato, vigoroso e sempre destinato a frantumarsi.

Dagli approcci respinti mediante lo scatto di un salto o di una contrazione, ai momenti di danza solista in cui i caratteri (angosciata e senza scampo lei, quasi più solido e fermo lui) si delineano con evidenza, fino al groviglio sfinito dei corpi, il lavoro si struttura seguendo una coerente e intensa progressione drammaturgica.

Senza mai scivolare neppure lontanamente nella didascalia o nella narrazione, la coreografia di Kylián riesce a condurci all’interno di tutte le sfumature di questa relazione disperata, facendocene assaporare dolori, tensioni e struggimenti: basta la mano aperta di Timulak sulla testa della sua compagna Cayla a raccontare la volontà pervicace e disillusa dell’uomo che tenta di afferrare, anche se per un attimo, il fervore angosciato della donna.

Ma non è abbastanza: nemmeno l’atto di Cayla di togliersi la maglietta rosso fiammante, che, lasciandola a torso nudo come il suo partner, sembra quasi alludere a una qualche simbiosi fra i due, riesce a risolversi poi in un autentico congiungimento.

Fino a che, nella commovente scena finale, con Cayla come inghiottita dal pavimento, si materializza l’inevitabile epilogo di una fine già dolorosamente annunciata.

Sylvie Guillem torna protagonista in “Bye”, assolo creato da Mats Ek in cui le capacità tecniche della danzatrice vengono piegate con sapienza alle esigenze di un’interpretazione particolarmente impegnativa, tutta giocata sulla dialettica fra abbrutimento del corpo ed esplosioni di vigoria e atletismo impeccabili.

La lunga treccia di capelli ramati che le sventaglia dietro la schiena, Guillem, quasi dimessa con indosso camicetta, longuette e golfino, dà vita a un vero e proprio dialogo con se stessa: come davanti a uno specchio, l’artista guarda dentro di sé e scorge la donna, proprio mentre quest’ultima non può rinunciare alla tentazione di strapparsi di dosso le scarpe e fendere l’aria con salti poderosi.

L’intero brano si nutre delle fragilità della donna ordinaria, che si stringe nelle spalle incurvate e cammina col passo di chi non vuole disturbare, così come del brio, del fuoco e del calore di una danza splendente di perfezione.

Ma non è un’immagine gloriosa quella con cui Sylvie Guillem ci rivolge il proprio saluto: nascostasi dietro a un piccolo schermo posto sul fondo (sul quale compaiono, oltre a lei stessa, figure diverse, da un uomo misterioso a un cagnolino fedele), ecco che la sua immagine riappare proiettata insieme a quella di molte altre persone che, lanciatoci un ultimo sguardo, si dissolvono alla spicciolata.

Un’occhiata, e via: l’artista scompare e il pubblico, avrebbero detto i critici d’antan, le tributa un trionfo.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

source: newizvru

Гиллем танцует уже много лет, но в детстве она занималась спортом, а о балете и не помышляла. И кто знает, как сложилась бы судьба юной гимнастки, если б не внезапное увлечение танцем. Так теперь и пишут во всех справочных изданиях: педагоги школы при Парижской опере увидели «экстраординарные физические возможности» девочки.

Уже в 19 лет молодая танцовщица Оперы стала прима-балериной этого прославленного театра, причем звание присвоил лично Рудольф Нуреев, возглавлявший тогда балет в Париже. И было за что: такого исполнения «Лебединого озера» в этом городе, избалованном прекрасными танцовщиками, не видели, может быть, никогда. В 1986 году Нуреев сочинил для Гиллем танцы в спектакле «Золушка», где ее героиня жила в Голливуде. Войдя в какой-то момент в конфликт с руководством театра (ее не отпускали на личные гастроли), Гиллем в апогее славы перебралась в Королевский балет Великобритании, и балетоманы отовсюду стали ездить в Лондон, чтобы увидеть это невероятно работающее тело, уникально приспособленное к танцу и обточенное до блеска французской балетной традицией. Сама Гиллем скромно относит свои дарования к хорошей наследственности. В московском интервью она так и сказала: «Мне дали очень хороший грузовичок, который меня вез по прекрасным дорогам».

С годами у примы остыл интерес к классике, хотя она покорила ею мир, выступая везде – от Лиссабона до Нью-Йорка и Сиднея. Настал черед современного танца – и снова невероятный успех. В нее творчески влюбляются самые лучшие европейские хореографы. Морис Бежар подарил Гиллем свое знаменитое «Болеро» и под ее дарование сделал балет «Сисси» – об эксцентричной австрийской императрице XIX века. Уильям Форсайт специально поставил балеты France Dans и In the Middle Somewhat Elevated. Джон Ноймайер из Гамбурга создал соло в балете Magnificat, Матс Эк сочинил балерине два фильма-балета – «Мокрая женщина» и «Дым». Увы, все это, как и большинство выступлений балерины в классике (лишь раз танцевала в Петербурге), прошло мимо России. К счастью, на сегодняшний день Гиллем продолжает делать разнообразные личные проекты, один интереснее другого, и уже в третий раз за последние годы приезжает с ними в Москву.

Программа «За 6000 миль» поименована по расстоянию, отделяющему Лондон от Токио. У Гиллем особо нежное отношение к Японии. И когда, находясь в Англии, она услышала грустную новость о землетрясении на Дальнем Востоке, название нового спектакля возникло само собой. Первый балет программы («27`52“»), поставленный в 2002 году, Гиллем не танцевала. Композицию, озаглавленную минутами и секундами, исполняли Аурелия Кайла и Лукаш Тимулак, специалисты по творчеству автора балета – Иржи Килиана. Одетые в майки и джинсы, они двигались в лучах слепящих прожекторов, демонстрируя столь же слепящий танец: иногда эта пластическая речь под современную колючую музыку напоминала любовный бред, а иногда – скандал.

Два других балета отличались друг от друга, как ночь и день. Уильям Форсайт сделал для Гиллем балет Rearray на музыку Дэвида Морроу, и балерина идеально оправдала название (что-то вроде «вновь рожденной структуры»). Ее «антиклассичекие» угловатые ракурсы чаровали не меньше, чем красивейший подъем выгнутой стопы или протяжные арабески. Умение структурно мыслить – и чувствовать – телом сделало Гиллем незаменимой для форсайтовских абстрактных измерений, проникнутых светом чистого разума. Тем более что премьер Парижской оперы Николя ле Риш ей в этом всемерно помогал, а частые эффектные затемнения превращали танец в пространственную головоломку.

Хореограф Матс Эк, наоборот, поставил очень эмоциональный, хотя и без всяких сантиментов, балет Bye на музыку Бетховена. «Прощай» – это прощание с детством, прощание с определенным периодом карьеры, прощание с той женщиной, которой я была раньше и которой больше не являюсь», – говорит Гиллем. Ее героиня словно переворачивает страницы своей жизни. Сначала она смотрит на нас из зеркала, потом материализуется в облике «гадкого утенка»: кто признает в этом плохо одетом и как будто нескладном существе прекрасного лебедя? Но вот сброшены ботинки и носки, слетает с плеч простецкая кофточка, нелепость сменяется вдохновением, и женщина, изменившись, двигается так, что публика цепенеет. И финальный уход в зеркало, где ее ждут изображения людей и зверей, не означает печального конца. Это просто новый этап жизни. Гиллем легко добивается невозможного: ее танец становится волшебным уходом от обыденности, и в то же время он необходимо актуален. Московские зрители, устроившие балерине овацию, легко могли бы подписаться под словами одного из европейских рецензентов: «Мир трепетал у ее прекрасных ног».